Rothko/Sugimoto: Dark Paintings and Seascapes, Pace Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Rothko/Sugimoto: Dark Paintings and Seascapes, Pace Gallery

Rothko/Sugimoto: Dark Paintings and Seascapes, Pace Gallery

Not so much a conversation, more an intriguing counterpoint duet

Half-way through Death in Venice, Thomas Mann's tragic hero, Aschenbach, settles down on a beach to gaze out to the sea to "take shelter from the demanding diversity of phenomena in the bosom of boundless simplicity". Aschenbach is suddenly returned to earthly complications when the horizon is intersected by the boy he desires.

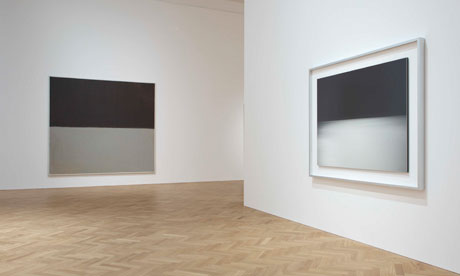

Both artists are juxtaposed here for the purpose of what the Pace Gallery describes as a visual dialogue. The similarities, on the face of it, are superficial: the works are characterised by a binary format of a black and grey surface and, as such, rhyme visually. But it is nevertheless an interesting pairing. The whispered subtleties alternately chime together on the same walls or face-off as counterparts on parallel walls.

Both artists are juxtaposed here for the purpose of what the Pace Gallery describes as a visual dialogue. The similarities, on the face of it, are superficial: the works are characterised by a binary format of a black and grey surface and, as such, rhyme visually. But it is nevertheless an interesting pairing. The whispered subtleties alternately chime together on the same walls or face-off as counterparts on parallel walls.

Rothko’s late black and grey paintings can be seen as a new direction or a dead end. Given the artist’s suicide not long after they were made, it’s tempting to read them as the latter. But despite the limited and arguably sullen palette, these works show a Rothko breaking out of his famously sumptuous mode of painting towards territory that is hard-edged and minimalist. Patches of paint no longer float like figures, replaced by bands of horizontal colour that evoke contemporaries like Ad Reinhardt and (early) Frank Stella. You can only wonder where Rothko could have gone with this new format were it not for his suicide.

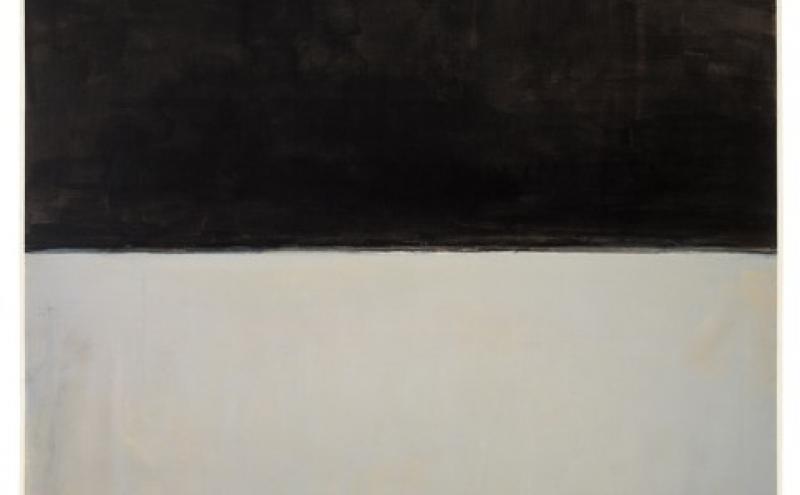

The first painting confronting the visitor entering the gallery has an opaque black, its grey section is more a soiled white. Broken brush scuffs of grey skip over the surface of black, and there is both speed and contemplation in the execution of this painting. To the left, Untitled,1969, has a translucent grey-black, over a muddy grey. Washes and dry-brushed scumbles animate the veil of paint with an anxious energy. A lot more than tiny differences set these two paintings apart, and they open the proceedings up beautifully. There's a language to them, rich in intonation if limited in vocabulary. To their right, Sugimoto's Liguran Sea, Saviore, 1993, has such a sharp contrast that it feels like a painting, as if the colours meet on its surface as blocks. But as you approach you can make out the dark water's low undulations emerging from a grey haze.

The first painting confronting the visitor entering the gallery has an opaque black, its grey section is more a soiled white. Broken brush scuffs of grey skip over the surface of black, and there is both speed and contemplation in the execution of this painting. To the left, Untitled,1969, has a translucent grey-black, over a muddy grey. Washes and dry-brushed scumbles animate the veil of paint with an anxious energy. A lot more than tiny differences set these two paintings apart, and they open the proceedings up beautifully. There's a language to them, rich in intonation if limited in vocabulary. To their right, Sugimoto's Liguran Sea, Saviore, 1993, has such a sharp contrast that it feels like a painting, as if the colours meet on its surface as blocks. But as you approach you can make out the dark water's low undulations emerging from a grey haze.

As you turn into the second suite of pictures, things diversify a little more. Sugimoto's images diverge from the bisected format, some carrying soft patches of light that are hard to imagine as vast swathes of water. The largest Rothko (which is huge) taking a central place in the gallery seems to ground not only the images around it but also the people. Its extreme - but not hard-edged - horizontal of two metres or so foregrounds the living figures that intersect it in a way that a shoreline gives distant silhouettes an existential gravity. It’s this animation of the surroundings around the pictures that is most minimalist about them, that emphasises the break Rothko had made from his earlier work, not only in form but in the spirit in which they were intended: less imagistic and contemplative, more sculptural.

Sugimoto's nature-capturing work is of course softer. Lake Superior, Cascade River, 2003, is almost monochrome, a uniform faint grey except, as you look closer, for the skeins of little waves that evaporate again as you step back. All these photographs situate you at the cusp not just of land, but also, in the imagination, at the cusp of consciousness in their evocation of a kind of primordial sublime. While Rothko’s late paintings attempt to turn away from romanticism, Sugimoto wholeheartedly embraces the tradition. Given that Sugimoto claims to have been driven in this direction by seeing these particular Rothko works in 1978, the notion that there’s a dialogue going on here starts to slip a little. This isn’t a conversation, this is a counterpoint duet.

Sugimoto's nature-capturing work is of course softer. Lake Superior, Cascade River, 2003, is almost monochrome, a uniform faint grey except, as you look closer, for the skeins of little waves that evaporate again as you step back. All these photographs situate you at the cusp not just of land, but also, in the imagination, at the cusp of consciousness in their evocation of a kind of primordial sublime. While Rothko’s late paintings attempt to turn away from romanticism, Sugimoto wholeheartedly embraces the tradition. Given that Sugimoto claims to have been driven in this direction by seeing these particular Rothko works in 1978, the notion that there’s a dialogue going on here starts to slip a little. This isn’t a conversation, this is a counterpoint duet.

- Rothko/Sugimoto: Dark Paintings and Seascapes at Pace Gallery until 17 November

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment