Watt, Barbican Pit Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Watt, Barbican Pit Theatre

Watt, Barbican Pit Theatre

Barry McGovern and Samuel Beckett's bleak brilliance dazzle

It begins with a tall, thin man walking out of light and into darkness. There is much that remains murky in Barry McGovern’s adaptation of this novel by Samuel Beckett, written between 1941 and 1945 when Beckett, who had worked for the Resistance, was in the South of France on the run from the Nazis, and not published until nearly a decade after its completion.

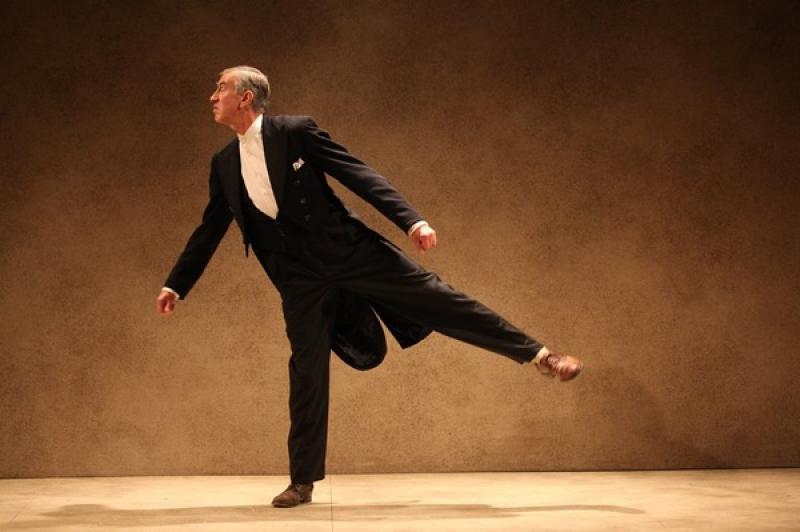

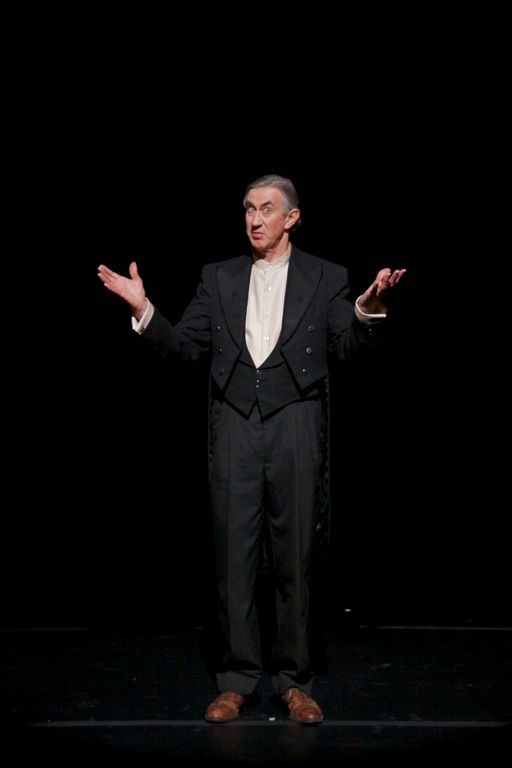

This 50-minute stage version, directed with an austere grace by Tom Creed for the Gate Theatre Dublin, and presented as part of the Barbican’s Dancing Around Duchamp season celebrating the avant-garde, can’t match the greatest of the plays for theatrical brilliance. But it has a quiet, desolate loveliness, a largeness of heart and spirit married to a despairing but dogged endurance. And it is beautifully acted by McGovern, a lone figure moving back and forth between light and dark, trapped by our gaze and by his own existence, a long-legged, weary moth, still capable of flutter and flourish.

In the darkness, McGovern removes his coat and hat and places them on a hatstand where they hang like a lean figure with bowed head. Stepping into a spotlight, he begins a narrative in which first and third person elide, where identities, events and memories are all equally elusive, and which begins with a train journey through a diseased landscape. From the windows, the crepuscular scenery looks ghastly; when the moon rises it is “unpleasantly yellow”. The traveller is Watt – his very name an ambiguity ("what") – and he is on his way to become a servant in the household of a man called Knott ("not"), of whom we learn even less. Of Watt, we hear that his smile is more like a sneer or a yawn; that his mouldering coat is turning green with age, his hat was found and appropriated at a racetrack, his shoes are stiff with seawater, his bags three-quarters empty; and that he gets little peace from the voices in his head.

In the darkness, McGovern removes his coat and hat and places them on a hatstand where they hang like a lean figure with bowed head. Stepping into a spotlight, he begins a narrative in which first and third person elide, where identities, events and memories are all equally elusive, and which begins with a train journey through a diseased landscape. From the windows, the crepuscular scenery looks ghastly; when the moon rises it is “unpleasantly yellow”. The traveller is Watt – his very name an ambiguity ("what") – and he is on his way to become a servant in the household of a man called Knott ("not"), of whom we learn even less. Of Watt, we hear that his smile is more like a sneer or a yawn; that his mouldering coat is turning green with age, his hat was found and appropriated at a racetrack, his shoes are stiff with seawater, his bags three-quarters empty; and that he gets little peace from the voices in his head.

On arrival, he is confounded by the nothingness of his post. There are visits from father and son piano tuners, a pair of twin dwarfs with “a medium-sized dog of repulsive aspect”, and from a fish seller with whom Watt shares tired embraces and intermittent kisses while she swigs her stout. But there is a lack of substance and order to it all that disturbs him; language itself begins to break down, words lose their meaning and with it their attachment to objects and events.

The language is lip-lickingly vivid and precise – Watt, picking his nose, is described as “masturbating his snout”, his longing for linguistic sense is a search for “semantic succour” – and McGovern, eyes bright and startlingly blue beneath bushy black brows, relishes every mouthful of it. He is at once nimble and achingly spent, grave, droll, compassionate and deeply melancholy. It is a stirring performance; and the whole is, in its brutal wit and bleak wisdom, a searing joy.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Add comment