The Gospel According to the Other Mary, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Dudamel, Barbican Hall | reviews, news & interviews

The Gospel According to the Other Mary, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Dudamel, Barbican Hall

The Gospel According to the Other Mary, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Dudamel, Barbican Hall

Adams's opera-oratorio mixes queasy evangelism and profound Passion to masterly ends

“I do not believe in miracles,” scoffs Herodias in Oscar Wilde’s - and Richard Strauss’s - Salome. “I have seen too many.” I know how she feels.

What that meant in practice, for me at any rate, was to sit through Act One compelled by every bar of a fluid, dynamic score which is so clearly in the blood and bones of conductor, players and singers, but simultaneously repelled by what sometimes felt like an hysterical and humourless Born Again rally. Act Two, though, dealing with the shock and awe of the Passion proper, redeemed all with the miracle of transformation.

In The Gospel According to the Other Mary – Magdalene, spotlit alongside more dutiful sister Martha and brother Lazarus – Sellars and Adams have gone beyond anything they’ve done before: the director by refining, the composer by expanding timespans, transitions and orchestral colours (this time the Hungarian cimbalom adds a special new sonority). As the programme fails to tell us, Adams has also thoroughly overhauled and trimmed the score since its 2012 premiere in Los Angeles’s Walt Disney Hall; the now-acclaimed revision was heard there 10 days ago before heading for various premieres in European countries including this long-awaited UK first.

The material they had to work with didn’t always make things easy. In the mosaic of texts which Adams has preferred since the departure of Alice Goodman, surely the finest poet-librettist since Hofmannsthal, strands come and go. Mary and Martha for All Women offer brief contemporary resonances in the opening scene of the former’s imprisonment and the latter’s home for destitute women, as well as later – more powerfully – in the parallel of their arrest with César Chavéz’s farm worker protests and Dorothy Day’s Catholic Worker Movement’s campaign for social justice. Sellars mirrors this simply but powerfully in the choral mime of praying women and brutal policemen.

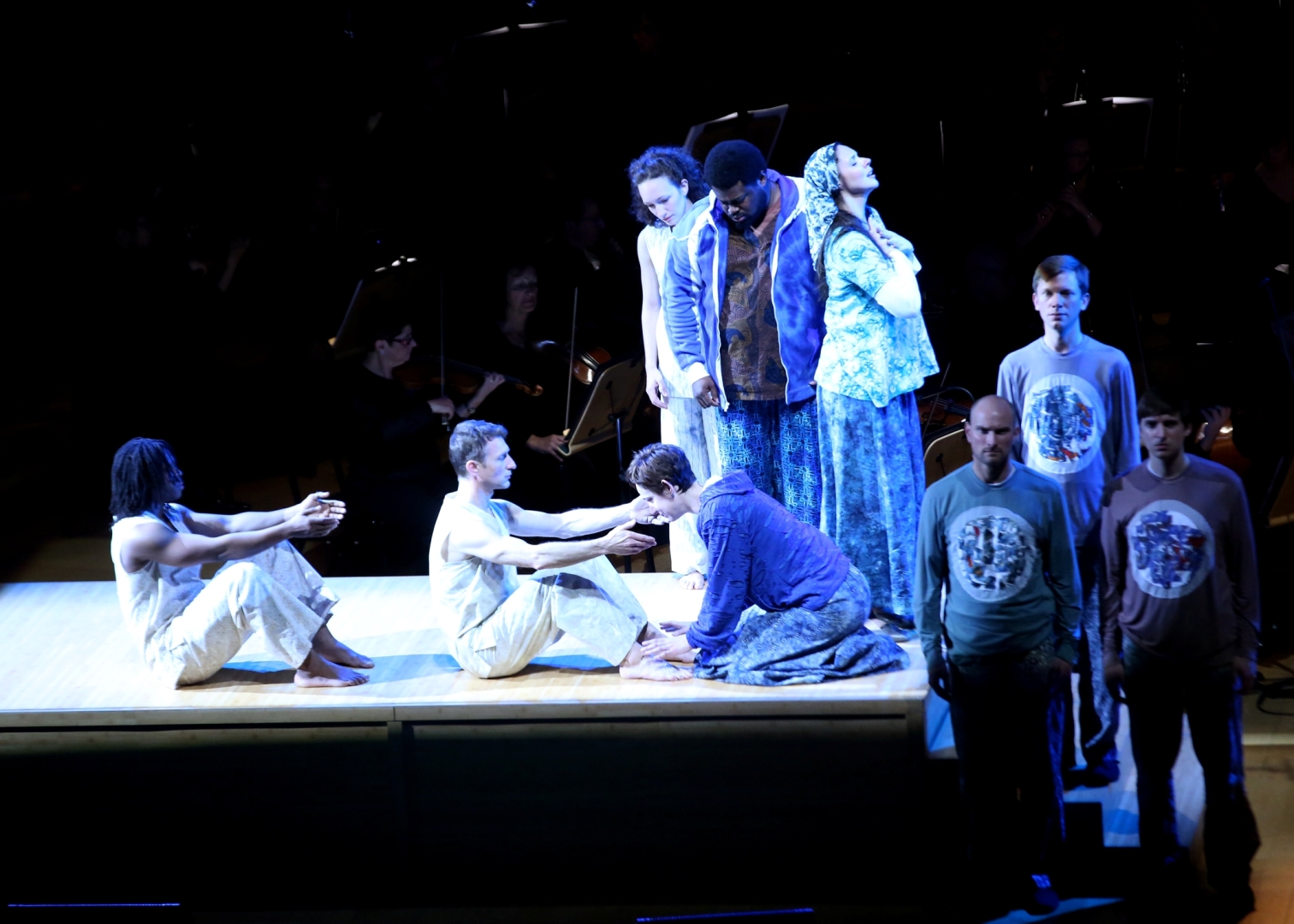

Otherwise the force is with Jesus, whose agony is rivetingly enacted by dancers Michael Schumacher and Anani Sanouvi, while his words pass between a trio of mostly close-harmony countertenors, as in El Niño - Daniel Bubeck, Brian Cummings and Nathan Medley, all superlative – and a tenor verging on the heroic. Russell Thomas’s Lazarus takes on the Christ role in a climactic aria at the end of Act One set to Primo Levi’s wonderful poem Passover. The emotional release is akin to Oppenheimer's “Batter My Heart” in Adams’s Doctor Atomic, but utterly different in its pace and more inward feeling. Thomas’s strenuous moment of heart-pounding anguish comes in Jesus’s reproach from the cross to the father who has abandoned him.

Adams asks for extremes from his singers. In both Kelley O’Connor and Tamara Mumford he has found mezzos who come close to the late Lorraine Hunt Lieberson’s extraordinary intensity and who effortlessly produce the contralto notes so often called upon. His finest achievement is to micromanage the curves of emotion which, while they may occasionally ease, never let the listener sit back for a moment. A self-effacing Dudamel and a sleek LA Phil seemed to have it all in the palms of their masterly hands. Yet despite beautifully crafted solos from O’Connor and Mumford in Act One, echoed in what has become hallmark writing for wind and brass solos since the First Lady's exquisite aria “This is prophetic” from Nixon in China – Whitney Crockett’s bassoon solo to reinforce Mary Magdalene is unforgettable – Act One’s tone is edgy and anxious, which may account for the religious zeal I found so uncomfortable.

Yet the much more subdued – and this time oddly believable – miracle of Christ’s reappearance in the garden (angels in the sepulchre pictured above left) was always going to be the biggest challenge. Adams and Sellars chart it with spellbinding eloquence, nearly consonant chords shifting to bring the focus back to Mary and her revelation. “The chill of grace lies heavy on the morning grass” sings Goodman’s Chou En-Lai in a similar moment of transcendence at the end of Nixon in China. That Adams has carried that transcendence off so differently three times – at the ends of Nixon, El Niño and now The Other Mary – would be quite enough to earn him a place among the immortals.

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Peter Sellars genius? If

Do you know, I think it

Do you know, I think it probably was genius at that time, even if such productions are the norm now. Don't get me wrong: some of his shows I've actually hated (his over-videoed Merchant of Venice with terrible verse speaking, his over-earnest attempt to make social commentary out of Mozart's flimsy Zaide), but when he's good he's great. And I've never encountered a more compelling speaker-animateur.

One of the things I