theartsdesk in Prague: Two Faces of Mucha | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Prague: Two Faces of Mucha

theartsdesk in Prague: Two Faces of Mucha

The great Czech pioneer of art nouveau has a pair of shows, one of them curated by Andy Murray's coach

The work of Alphons Mucha (1860-1939) is immediately identifiable with its decorative flowers, delicate colours and wide-eyed women staring seductively at the viewer. He was one of the pioneers of art nouveau and the art of advertising. In Prague an exhibition recently opened which is packing them in at the glorious art nouveau Obecni Dům (Municipal House) in the centre of the city.

Ivan Lendl: Alphons Mucha is the most comprehensive exhibition of Mucha’s original posters and graphic work ever presented – from the collection put together by Czech-born tennis star Ivan Lendl over the past 30 years. “At the Davis Cup in 1982”, he writes, “my coach Jan Kukal introduced me to Jiři Mucha (the artist’s son) and that’s where it all started.” Perhaps to emphasise the tennis connection, the two exhibition rooms have a carpet of artificial grass on the floor.

Although born in the Moravian town of Ivančice, Mucha made his name in Paris. The exhibition includes his earliest work – Gismonda (1894-5), a poster of Sarah Bernhardt for her theatre company. He seemed to arrive with all his distinctive stylistic ingredients in place – arabesques curling into every space, the flowing hair and richly patterned clothes. There are also posters for several "farewell" tours: her Farewell American Tour (1905-6) and Last Visit to America (1910-11).

Although born in the Moravian town of Ivančice, Mucha made his name in Paris. The exhibition includes his earliest work – Gismonda (1894-5), a poster of Sarah Bernhardt for her theatre company. He seemed to arrive with all his distinctive stylistic ingredients in place – arabesques curling into every space, the flowing hair and richly patterned clothes. There are also posters for several "farewell" tours: her Farewell American Tour (1905-6) and Last Visit to America (1910-11).

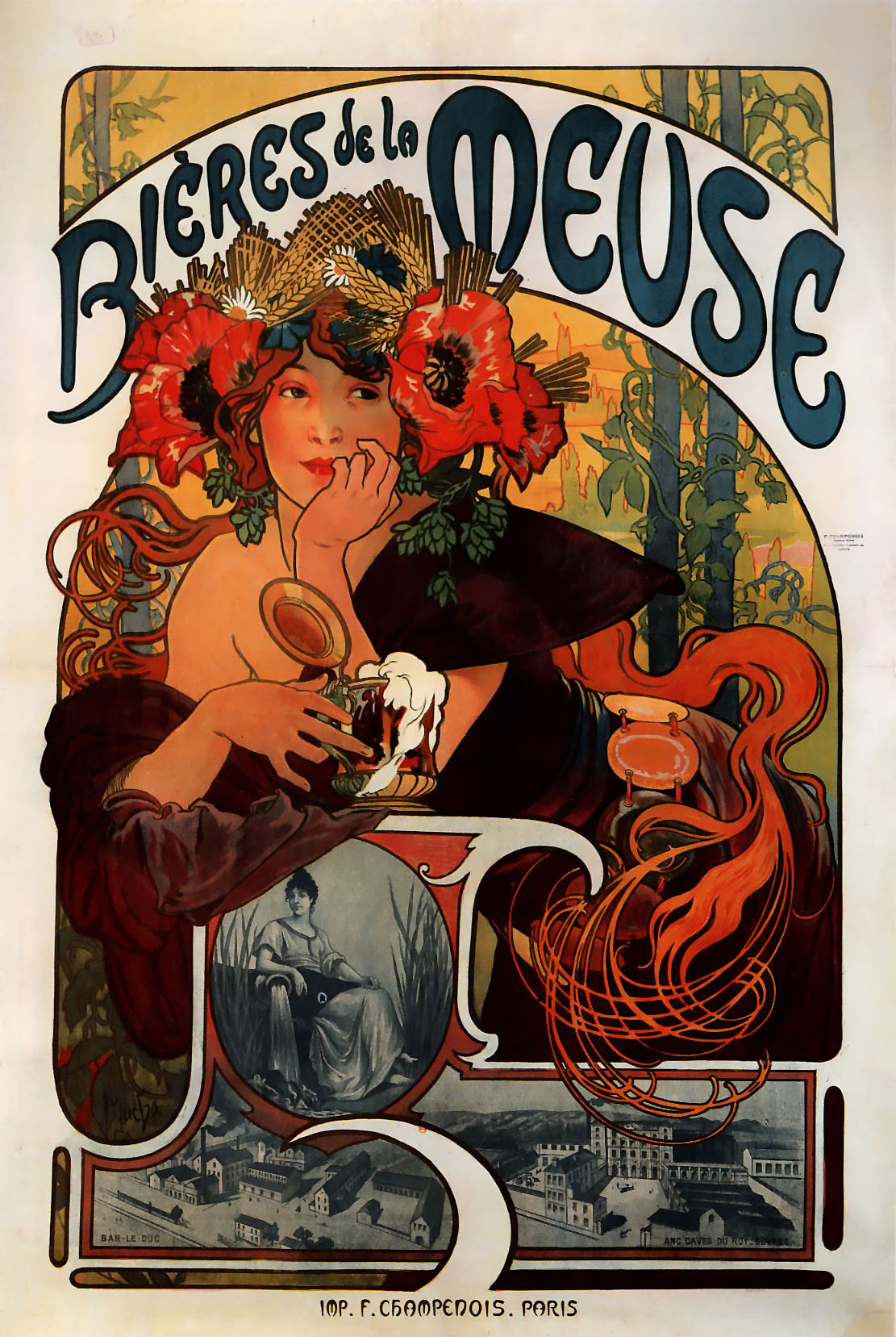

Mucha was one of the first artists to be taken up for advertising work – by biscuit company Lefèvre-Utile, Nestlé and Bières de la Meuse – his 1897 poster for them is one of his most reproduced (pictured above). A voluptuous brunette with poppies in her hair holds a frothing tankard of beer while her flowing locks form decorative curlicues. Or from the same year, Hommage Respecteux de Nestlé is a tribute to Queen Victoria for her Diamond Jubilee (pictured below). The queen is seen both young and old in front of silhouettes depicting Britain’s industrial power, seafaring trade and empire, including buildings from the Indian Raj.

Seeing these 122 works together, you understand how Mucha found a formula and stuck to it – a generic beauty gazes out at the viewer, framed by a circle which is then inventively decorated by flowers, cascades of hair or the steam from hot chocolate. He even produced a style guide and then became irritated when his hugely successful style was imitated.

Around the turn of the century his interest started moving in different directions. In 1900 he decorated the interior of the Bosnia-Hercegovina pavilion at the World Fair in Paris and he came up with the idea of painting a large scale series of pictures called the Slav Epic (Slovanská Epopej). This was the time of rising nationalism in Central and Eastern Europe and a pan-Slavism amongst many prominent Czech artists – like Mucha, Mikoláš Aleš and composer Leoš Janáček.

Around the turn of the century his interest started moving in different directions. In 1900 he decorated the interior of the Bosnia-Hercegovina pavilion at the World Fair in Paris and he came up with the idea of painting a large scale series of pictures called the Slav Epic (Slovanská Epopej). This was the time of rising nationalism in Central and Eastern Europe and a pan-Slavism amongst many prominent Czech artists – like Mucha, Mikoláš Aleš and composer Leoš Janáček.

Mucha went to America in 1904 and met philanthropist Richard R. Crane in Chicago. Crane became interested in Slav nationalism, invited Thomas Masaryk, the future president of independent Czechoslovakia, to Chicago, and agreed to finance Mucha’s Slav Epic. One of the few posters Mucha did at this time was for the Slavia insurance company (1907) which features Crane’s daughter as the model with flowers in her hair and peasant ribbons. The colours are predominantly the red, white and blue of the Czech flag which was not allowed to be displayed at the time. Mucha returned to his homeland in 1910 and the Slavia design was re-cycled when the artist was commissioned to design the new banknotes and stamps for independent Czechoslovakia in 1918.

At the end of the Ivan Lendl exhibition is a painting called The Pantheon of Czech Music (1929). Of the half-dozen figures, I can recognise only Dvořák and Smetana in the centre and the whole tone is elegiac with peasant girls grieving and a violinist bent over as if she’s playing a lament. It’s in a totally different style to his posters – a sort of allegorical realism which also pervades the paintings of the Slav Epic.

The 20 massive canvases of the Slav Epic – painted on ship sail between 1912 and 1928 – went on view in Prague only in July last year. Following a controversial legal case, they were taken from the castle in Moravský Krumlov (pictured), near the artist’s birthplace, where they had been on show since 1963. The Epic is now on show at the Veletržní Palac (Trade Fair Palace), a branch of the National Gallery, in an exhibition organised by the Prague City Gallery, who supplied my excellent guide Adéla Dorňáková.

The 20 massive canvases of the Slav Epic – painted on ship sail between 1912 and 1928 – went on view in Prague only in July last year. Following a controversial legal case, they were taken from the castle in Moravský Krumlov (pictured), near the artist’s birthplace, where they had been on show since 1963. The Epic is now on show at the Veletržní Palac (Trade Fair Palace), a branch of the National Gallery, in an exhibition organised by the Prague City Gallery, who supplied my excellent guide Adéla Dorňáková.

I’d seen pictures of the canvases online, but nothing prepares you for the (literally) huge impact they have for real – the largest ones are 8x6 metres and overwhelming to look at. The opening image of The Slavs in their Original Homeland depicts a defenceless man and woman at the mercy of invading hoards. The dominant figure is a pagan priest hovering in mid-air, flanked by a woman representing peace and a man representing war. But what made the strongest impression on me was the shining intensity of the stars in the night sky. The first three canvases all have a "realistic" scene depicted on the bottom half of the canvas and then mythological or symbolic figures, like the pagan priest, superimposed as if in a parallel universe. The Celebration of Svantovit in Rügen depicts a pagan celebration resisting Teutonic conversion to Christianity and the Introduction of the Slavic Liturgy shows Prince Svatopluk embracing the Orthodox faith in the Moravian heartland with the saints Cyril and Methodius. As someone celebrating Czech independence from the Hapsburg Empire, Mucha is anti-German and particularly anti-Catholic in these pictures.

Ten of them depict Czech history and the rest portray scenes amongst other Slav peoples – including the Russians, Bulgarians, Serbs and Poles. But it’s hardly a definitive or accurate history. My guide points out that Charles IV, King of Bohemia in its golden age, responsible for Charles Bridge and Prague Castle, is absent, probably because he was also Holy Roman Emperor.

Ten of them depict Czech history and the rest portray scenes amongst other Slav peoples – including the Russians, Bulgarians, Serbs and Poles. But it’s hardly a definitive or accurate history. My guide points out that Charles IV, King of Bohemia in its golden age, responsible for Charles Bridge and Prague Castle, is absent, probably because he was also Holy Roman Emperor.

Several of the pictures are connected to the Hussites, the 15th-century religious reform movement, whom Mucha did support as they were fighting against the Catholics. Mucha being resolutely against war, two war canvases depict not the fighting, but the aftermath. We see the misery and devastation, but no blood or gore. The picture of The Hussite King Jiří of Poděbrady has the king scoffing at a cardinal from Rome who brings the message that the Pope won’t authorise the liturgy in a Slav language. A translator interprets as the king doesn’t understand Latin. The Royal Court where this meeting took place in 1462 was demolished to build the Obecni Dům, which Mucha was commissioned to decorate and where the poster exhibition is currently displayed.

While most of the canvases of the Slav Epic have a historical sweep, there’s one with an intense emotional power. It shows Jan Amos Komenský (Comenius), the father of modern education (depicted on the current 200 koruna banknote) at the end of his life, in 1670. He’s in exile in the Netherlands for his protestant beliefs, in a dark, wintery landscape, sitting alone by the sea, hunched as if remembering his homeland. It’s the only painting in the Epic that Mucha signed (pictured above right)

While most of the canvases of the Slav Epic have a historical sweep, there’s one with an intense emotional power. It shows Jan Amos Komenský (Comenius), the father of modern education (depicted on the current 200 koruna banknote) at the end of his life, in 1670. He’s in exile in the Netherlands for his protestant beliefs, in a dark, wintery landscape, sitting alone by the sea, hunched as if remembering his homeland. It’s the only painting in the Epic that Mucha signed (pictured above right)

The penultimate picture shows the Abolition of Serfdom in Russia (pictured top of page). The scene is 1861 and is recognisably against a backdrop of St Basil’s Cathedral on Red Square. It’s not a scene of jubilation but one of desolation and uncertainty at what still has to be accomplished. The final scene, Apotheosis "Slavs for Humanity", attempts to bring the different strands of the series together – prehistory, the Middle Ages, and the flags of the victorious nations in the First World War dominated by a heroic Slavic figure with Christ behind him. It’s not altogether successful and, in retrospect, has uncomfortable overtones of Socialist Realism.

The Slav Epic is apparently hugely popular with Japanese tourists

Having been one of the pioneering figures of art nouveau and the advertising poster, Mucha was criticised by many for the anachronistic style of the Slav Epic. But there were many artists in Europe embracing similar themes of national revival at this time. In Finland, Akseli Gallen-Kallela (1865-1931) decorated the Finnish pavilion at the Paris World Fair in 1900 and went on to paint a whole cycle of paintings inspired by the Kalevala epic in a similar style of mythological realism. In Russia, Ilya Repin (1844-1930) drew attention to the realities of peasant life and might have been an inspiration for Mucha’s Red Square canvas.

At first glance, Mucha’s two styles – the poster and the epic - seem to have little in common. But if you look carefully, there are clear echoes from his earlier work - the decorative architectural backgrounds of palaces and churches, the flowers and linden leaves (a national symbol) that manage to penetrate through the action, and particularly the faces that stare out of these canvases and look directly at the viewer. They are always the ordinary people - a peasant, or a mother with her child - not the important historical characters.

As a known Czech nationalist, Mucha was arrested by the Gestapo in 1939 for questioning and died soon after. The Slav Epic was hidden in occupied Czechoslovakia and, after the war, Mucha was seen as decadent by the Communist regime so no effort was made to display them. It was the town of Moravský Krumlov that went out of its way to exhibit the cycle and it’s easy to understand their annoyance at their major tourist draw now being relocated to Prague. The Slav Epic is apparently hugely popular with Japanese tourists and thousands went to Moravský Krumlov every year to see it. But the display in Prague is magnificent and don’t imagine that you have any idea of the power of these paintings from the reproductions here. Go while you can, it should be on show for a couple of years – after which there’s talk of sending them on loan to Japan!

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Comments

Would love to go to this. The

Curated by Ivan Lendl, no