A Crisis of Brilliance, Dulwich Picture Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

A Crisis of Brilliance, Dulwich Picture Gallery

A Crisis of Brilliance, Dulwich Picture Gallery

A rich anthology of experimental British art in the years leading up to and during the First World War, plus gallery

The very tall, skeletal and formidable Henry Tonks (1862-1937), surgeon and anatomist, became one of the most decisive, influential, scathing and inspirational teachers in the history of visual education. At the Slade, in his second career as artist and teacher, he presided over several generations of London-based artists who formed the bedrock of modernism, from the absorption of Impressionism to the various isms of the turn of the last century.

It is the generation who first gaily embraced the bohemian freedoms of art school and then were tempered by the horrors of World War I (Tonks himself served not only as a war artist but as a doctor) that is under examination in this truly revelatory exhibition. Several have only relatively recently been revalued – CRW Nevinson and David Bomberg, for example – while others have been studied, shown, admired and honoured for several generations, notably the eccentric Stanley Spencer.

The unsmiling grave faces of the artists look out with a kind of guileless innocence before harsh realities intrude

The iconic Slade School of Art picnic photograph of 1912 shows us a solemn group of students, subliminally conspiratorial, with more women than men. There is little visible hint of the amatory entanglements in various permutations, not to mention two suicides – and one murder – to come, let alone the tenacious game-changing achievements in paint that were being nurtured behind these guileless façades. The teachers, pipe-smoking, moustachioed, in their three-piece suits, stand behind this uncontrollable crew of students, the dominant middle class ethos leavened by the two first-generation eastern European immigrants, the working-class descendants of the ghetto: poverty-stricken David Bomberg and Mark Gertler. On view here is Gertler’s unusually touching and curiously disturbing 1913 The Rabbi and his Grandchild, depicting a wise old man, bowed down it seems by centuries, gently touching the face of his impassive granddaughter

Tonks was an art conservative who tried to forbid his students from visiting Roger Fry’s great exhibitions of 1910 and 1912 which brought Post-Impressionism and the European avant-garde to Britain. So it is even more astounding that within the Old Master frame of Dulwich the first masterpiece from the period that greets the visitor is Bomberg’s 1913-1914 In the Hold, painted in his early 20s: a sparkling abstract series of interlocking geometric shapes, imagined and refined from close observation of the rhythms of dockside labourers. The sense of vitality, of disciplined experimentation, is contagious: here is visual intelligence of the highest order, original, enthusiastic, open to the new world order. As he said, he wanted “to translate the life of a great city, its motion, its machinery, into an art that shall not be photographic, but expressive.”

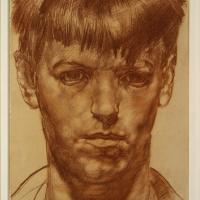

The exhibition, over 70 paintings and drawings, moves from early student days to the war, from emerging talent to a few works so memorable, so fervent, so innovative, that they border on genius. Throughout there are a series of dignified and touching self-portraits: the unsmiling grave faces of the artists look out with a kind of guileless innocence before harsh realities intrude. They were to make their way through a labyrinth of intense emotional attachments and an indifferent or contemptuous critical world, but make it most of them did, at least with the hindsight of a century’s perspective.

Many of the works, from private collections or not normally on public view, are a surprise. One such is another huge Bomberg, Sappers at Work, which was rejected by the Canadian War Memorial and here shown to be replete with an awesome energy, unusual verve expressed in unexpected colour and fragmented form, the whole communicating a vital energy directed to some communal and significant purpose.

Paul Nash once said of his own war paintings, that they possess a “towering audacity”. In Void (pictured right) we find that Expressionism meets Futurism and even anticipates Surrealism in the combination of recognizable elements, the twisted metal of weapons tumbled together in a scene that also defies reality, but gives form to the horrors and terrors of the leftovers of the newly mechanized aggression of conflict.

Paul Nash once said of his own war paintings, that they possess a “towering audacity”. In Void (pictured right) we find that Expressionism meets Futurism and even anticipates Surrealism in the combination of recognizable elements, the twisted metal of weapons tumbled together in a scene that also defies reality, but gives form to the horrors and terrors of the leftovers of the newly mechanized aggression of conflict.

Meanwhile, Nevinson’s Dance Hall Scene is a riot of colour, of human forms in an arrested choreography. And Le Vieux Port shows, in a kind of cubo-realism, a stylized arrival of a ship into harbour, complete with manikin passengers, set against a towering heap of dockside buildings.

Two extraordinary Nevinsons show his hard-won ability to harness style to fine tune exactly what he wanted to show, to convincingly portray a spectrum of human experience. La Patrie is truly shocking: Nevinson was portraying what he found in an old railway shed packed with 3,000 dead, dying or wounded soldiers, as he indicated an inconceivable nightmare. Although the figures are shrouded you can almost smell the suppurating wounds.

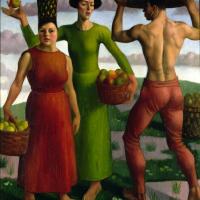

Some bucolic scenes come from Stanley Spencer, from apple gatherers to the gathering at a war memorial in Berkshire, both freighted with the symbolic meaning he so characteristically gave to daily life. And then there are Dora Carrington’s awkward but heartfelt paintings of the countryside. The anthology shows us the chrysalis of student life, and the bursting forth of talent, roughly disciplined and nurtured into a hard won maturity.

A Crisis of Brilliance at Dulwich Picture Gallery until 22 September

Click image below to view gallery

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment