Prom 60: Billy Budd, Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Davis | reviews, news & interviews

Prom 60: Billy Budd, Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Davis

Prom 60: Billy Budd, Glyndebourne Festival Opera, Davis

A neat craft sails into the Proms, and the Captain shines, but there's always some defect

You may well ask whether theartsdesk hasn’t already exhausted all there is to say about Glyndebourne’s most celebrated Britten production of recent years. I gave it a more cautious welcome than most on its first airing, troubled a little by the literalism of Michael Grandage’s production and the defects in all three principal roles.

It did, and in the usual unexpected ways. Padmore, possessing the smallest of the three lead voices, projected best right to the back of the hall, where I was this time sitting, with crystal clear inflection and articulation of every phrase, making the most intimate moments the most telling. By which I mean the Prologue, in which Vere looks back on 1797 and his ship the HMS Indomitable’s role in the Napoleonic Wars, and the Epilogue, where he sees Billy’s sacrifice as his own personal – sexual, imply the librettist of the Melville story E M Forster and Britten – liberation. The big final major-key triad, heart-stopping from the London Philharmonic under Sir Andrew Davis, and its fade to nothing, the voice left alone and Padmore walking off to total silence, were as stunning a couple of moments as any in this year’s Proms operas.

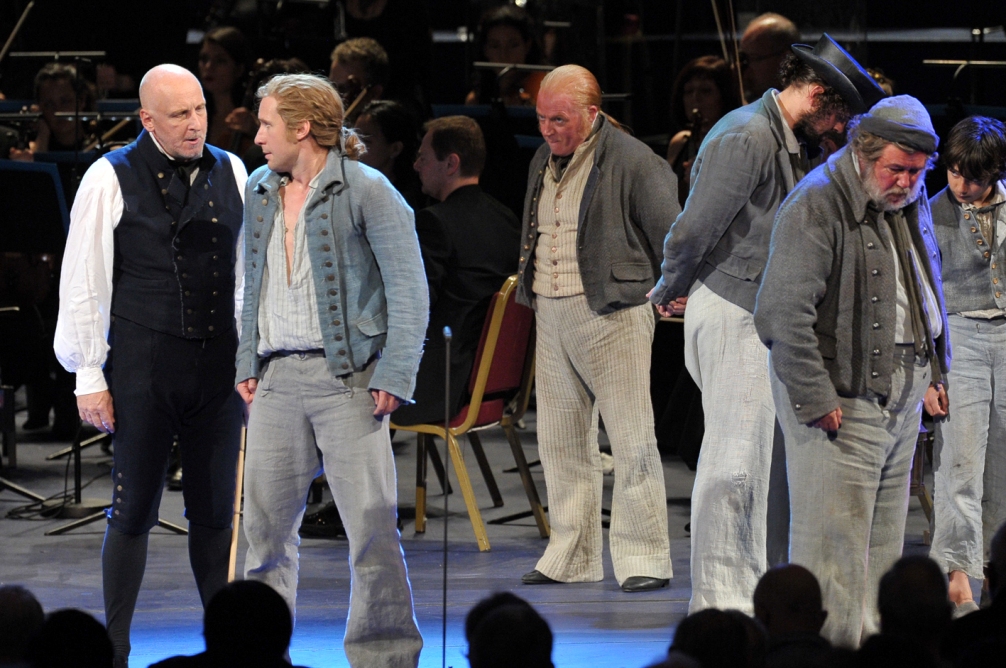

If only what went before had been consistently up to that level. The big disappointment, in this venue at least, was Brindley Sherratt’s Claggart (pictured with Jacques Imbrailo's Billy to the left of the picture). No suggestion here of Forster’s “sexuality gone soggy”, and though Sherratt has always been a true bass, there was none of the inky-black resonances that had so cut through the Albert Hall murk in Eric Halfvarson’s and Stephen Milling's Ring giants and even the now-controversial Wagner performance of Sir John Tomlinson, the greatest of all Claggarts. Maybe Sherratt is more cut out to be a noble sort, as his peerless Pimen, Sarastro and Pogner have already proved.

If only what went before had been consistently up to that level. The big disappointment, in this venue at least, was Brindley Sherratt’s Claggart (pictured with Jacques Imbrailo's Billy to the left of the picture). No suggestion here of Forster’s “sexuality gone soggy”, and though Sherratt has always been a true bass, there was none of the inky-black resonances that had so cut through the Albert Hall murk in Eric Halfvarson’s and Stephen Milling's Ring giants and even the now-controversial Wagner performance of Sir John Tomlinson, the greatest of all Claggarts. Maybe Sherratt is more cut out to be a noble sort, as his peerless Pimen, Sarastro and Pogner have already proved.

The object of Claggart's self-thwarted desire was, as in 2010, the Billy of Jacques Imbrailo: a likeable chap with a lightish baritone, sweet but not even innocently sexy or especially charismatic. Waiting in the wings as it were was a singer with a bigger voice and presence, Duncan Rock, who along with Peter Gijsbertsen (both pictured left), made the soulful sax-dominated scene of the aftermath to the Novice’s flogging a strong one (Rock will be singing Tarquinius in Fiona Shaw’s hugely anticipated Glyndebourne Touring Opera production of The Rape of Lucretia).

The object of Claggart's self-thwarted desire was, as in 2010, the Billy of Jacques Imbrailo: a likeable chap with a lightish baritone, sweet but not even innocently sexy or especially charismatic. Waiting in the wings as it were was a singer with a bigger voice and presence, Duncan Rock, who along with Peter Gijsbertsen (both pictured left), made the soulful sax-dominated scene of the aftermath to the Novice’s flogging a strong one (Rock will be singing Tarquinius in Fiona Shaw’s hugely anticipated Glyndebourne Touring Opera production of The Rape of Lucretia).

The rest of the ensemble and the Glyndebourne Chorus were as strong as ever, making the best in the hall of the “moment we’ve been waiting for” in Act Two before mists obscure the enemy. I wavered about the wisdom of having Ian Rutherford’s re-staging done in costume; the evening dress of Justin Way’s Wagner operas had seemed more liberating. But the realism of the one-to-ones certainly worked. Again, the more intimate scenes in Vere’s cabin, with the back projection working especially well, came across the most vividly – though Padmore is still taxed to express extreme anguish: you expect the searing of a Langridge, whose voice Padmore’s so often resembles, or a Pears, but it falls just a little short.

Davis (pictured right) cut through the cotton wool of the Albert Hall to give incision at every turn of Britten's finely calibrated orchestral screw, with magnificent focus in all departments from scything LPO brass down to Debussyan flute and harp reflections, while never quite billowing in all but the last of the big moments. So fine an achievement in many ways, so clearly the fruit of long-term teamwork, but it could have been so much more devastating. Until, of course, the end.

Davis (pictured right) cut through the cotton wool of the Albert Hall to give incision at every turn of Britten's finely calibrated orchestral screw, with magnificent focus in all departments from scything LPO brass down to Debussyan flute and harp reflections, while never quite billowing in all but the last of the big moments. So fine an achievement in many ways, so clearly the fruit of long-term teamwork, but it could have been so much more devastating. Until, of course, the end.

- Listen to this Prom for the next six days on the BBC Radio 3 iPlayer

- Preview of Glyndebourne's 2014 main season repertoire on the company's website

- Read theartsdesk's coverage of the Proms

- Read David Nice's blog, I'll Think of Something Later

rating

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

Hmm... I think,

Fair enough, Andrew, and I've

Fair enough, Andrew, and I've been very aware how specific my responses this season have been to where I've been sitting (and I only wish I'd gone down into the Arena more, like I usually do - only made it for the Late Night World Routes Prom - but it was nearly always so packed, and I needed stamina for the Wagners...). There are so many different perspectives possible for the Proms, radio and (sometimes) TV included. If only we had time to listen to it all again on R3 after the performance. No doubt, though, about Britten's status in this towering tragedy alongside Wagner.

Take your point about the Parsifalian dentistry - though clearly the white and later the black were symbolic - and not all the ladies' evening wear coincided with their characters (ie Anna Larsson, red as Erda).

Why does Billy have to

Why? Because the element of

Why? Because the element of sexual love/attraction to Billy in Vere's and Claggart's characterisations was absolutely central to Forster - less provably so to Melville - and the mixture of repression and liberation in Vere has to be (you may like to challenge that) what attracted Britten to setting the work in the first place. Not to mention the depraved aspect of Claggart linking to that now-inescapable knowledge we have of Britten's claiming to close friends to have been raped by a master at school.

Allen was disingenuous to suggest that anyone in the cast, or much of the audience, was ignorant of the composer's homosexuality in the early 1950s, or of the relationship to him of Pears for whom the role which comes to be so central was created. Moreover I know this opera had a huge impact on my closeted student self in the early 1980s, as I've since found out it did for others, for what it had to say to us, though the message is not a very happy one.

I'm not saying the whole production should be aimed exclusively at those elements - the richness of this masterpiece lies in its many dimensions - but you seem to me to suggest they should be underplayed, as I feel they always have been in Grandage's production. Not so Albery's, Vick's or Neil Armfield's (let's forget Zambello's; and how I wish I'd been around to see the Alden production last year). I still feel uncomfortable with the libretto's insistence on Billy with his 'defect' as a tool for Vere's emancipation; there are still troubling aspects, as there are in all of Britten's greatest works. I wanted to be troubled by them last night, but instead I watched with interest and was moved more by the music than by the situations. I don't think bonkers or banal fit the picture as I see it, thank you.

Dear Mr Nice, bonkers was

Many thanks for extending the

Many thanks for extending the debate, Robin (if I may, for I can't presume your sex from the name), and that's what I like - a bit of refining the argument in the process. As I should mine: I don't think Billy should be a 'sex bomb', and in defining the sexual attractiveness which I think is important I probably malign the admirable Mr Imbrailo; others may feel differently.

I just think the love-triangle aspect is possibly even more important than it is in Tosca: now she definitely needs to have divaish allure, don't you think, or she wouldn't turn Scarpia on so. Here, you're right, the sexual aspect is more subterranean, and that's part of the fascination about Vere's repression. If his resolution is just about conscience, how does that explain the emancipation? Just that Billy was an angel who lit the way? I actually don't find it dramatically quite right in any case, that epilogue with its shining sail (the music shared by Billy after Vere has visited him), but boy, musically does it pack a final punch.

One final analogy, with Shostakovich who similarly had to repress what he truly wanted to say for so long. What's underground in the Fifth and Sixth Symphonies finally gets made explicit in Yevtushenko's texts for the 'Babi Yar' Symphony, especially 'Fears', written and set to music nearly a decade after Stalin's death. And what Britten could not make so explicit under the criminal laws in Britain he finally did in the 1970s when Aschenbach stammers out about Tadzio what Vere would surely have done about Billy, 'I...love...you'. That it's about a young, if not necessatily pre-pubescent, boy makes it more fraught in the context of Britten's biography. Anyway, happy for anyone to challenge that.

We caught the last

From the rear of the