Australia, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

Australia, Royal Academy

Australia, Royal Academy

An arresting survey explores two hundred years of Australian art

In The Importance of Being Earnest, first performed in 1895, Oscar Wilde wittily quipped that Algernon must choose between “this world, the next and Australia”. At a time when it took weeks to reach the other side of the globe most Britons, if they thought of it at all, thought of that far-flung continent as a convenient corral for undesirable fellow citizens.

While for most contemporary Brits Oz probably means beach babes and Neighbours, starting life as a sort of annex for undesirables from the “mother country” left Australians with a sense of insecurity as to who and what they really were. This new exhibition at the Royal Academy attempts to construct a multi-faceted narrative of the continent by presenting more than 200 years of Australian art on the theme of land and landscape, dating from 1800 to the present day. From the works of the first colonial settlers, executed in a nation-building, pioneering spirit, to that of contemporary artists, Australia tells the story of a country that has slowly built an identity, no longer dependent on European tradition, through a relationship to its diverse landscape and peoples. To date it is the most comprehensive survey of Australian art to have been shown outside Australia.

It’s difficult not to respond to these beautiful and highly accomplished works without reference to modernist painting

Although arranged in chronological order, the first image encountered is contemporary: a video of a motorcyclist in black leathers – Shaun Gladwell’s Approach to Mundi, Mundi, 2007 - following the central white lines down a road that runs through the barren outback, his arms held aloft as if to emphasise the vastness of the empty landscape surrounding him. While Mundi is a local place name, it is also the Latin for “world” and the piece acts as something of a prologue, for, of course, Australia was not some virgin territory awaiting Europeans, but a landscape that has been inhabited for over 40,000 years. Believed to have first been “discovered” by the Dutch in 1606, the East Coast was then claimed in 1770 by the British, disturbing millennia of indigenous culture.

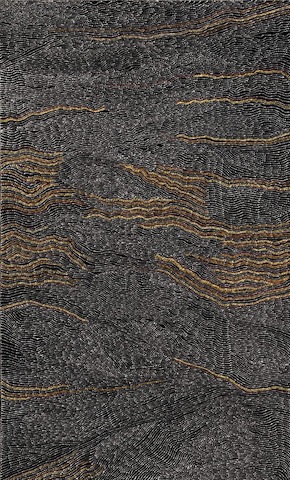

The exhibition begins with a fine collection of Aboriginal art which, to this day, continues to describe the sacred forces of the landscape and the creation stories or "Dreamings" that have symbolic significance and underpin the science, religion, rituals and identity of the indigenous peoples. There’s a certain irony that the revolution in modern Aboriginal art, which had its origins in the Western Desert in the 1970s, and brought Aboriginal art to a wider audience, appeals so, with its abstract and simplified forms and monochrome earthy colours, to European modernist sensibilities. As Europeans it’s difficult not to respond to these beautiful and highly accomplished works without reference to modernist painting. Yet what we wrongly read as “stillness” is, in fact, animated totemic activity and ancestral power. (Pictured left: Sandhills of Mina Mina, 2000, Dorothy Napangardi; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.)

The exhibition begins with a fine collection of Aboriginal art which, to this day, continues to describe the sacred forces of the landscape and the creation stories or "Dreamings" that have symbolic significance and underpin the science, religion, rituals and identity of the indigenous peoples. There’s a certain irony that the revolution in modern Aboriginal art, which had its origins in the Western Desert in the 1970s, and brought Aboriginal art to a wider audience, appeals so, with its abstract and simplified forms and monochrome earthy colours, to European modernist sensibilities. As Europeans it’s difficult not to respond to these beautiful and highly accomplished works without reference to modernist painting. Yet what we wrongly read as “stillness” is, in fact, animated totemic activity and ancestral power. (Pictured left: Sandhills of Mina Mina, 2000, Dorothy Napangardi; National Gallery of Australia, Canberra.)

The first British settlers to arrive in 1788 found Australia a bewildering and alienating continent. Early colonial artists focused on views of homely settlements rather than the, apparently, more threatening landscape. Gradually, however, the character of their adopted land was to become the main stimulus for Australian painting for the next 150 years. As with early American painting there is a pioneering sense of wonder at this vast country with its antipodean light and unfamiliar palette. Many painters, such as Arthur Streeton, created images of golden pastoral landscapes that were to become conventional expressions of Australian nationalism. But the Australian gold rush in the 1850s saw the population expand to include immigrants from Germany, Switzerland and France, who all brought their own native influences. Australian landscape painting was to change from the mainly British Romantic watercolour tradition to a German Romantic landscape tradition in oils, which reflected a sublime and philosophical relationship to the land. The most notable exponent was Eugene von Guérard (pictured below: Bushfire, 1859; Art Gallery of Ballerat).

Talk, for the first time, of an Australian tradition began with the Australian Impressionists who worked out of doors. Tom Roberts’ A Break Away, 1891, shows a quintessentially Australian scene of stampeding sheep in a parched landscape being rounded up by a heroic, horse-riding stockman. Modernity was to be summed up in the honed and architectural renderings of the building of Sydney Harbour Bridge that, after the Great Depression, became a symbol of hope for many. Some, such as Margaret Preston, did display in her landscapes a sensitivity to indigenous art, while others, such as Sidney Nolan, began to create new Australian narratives through the use of folklore and local legend, as in his famous series based on the Irish-Australian outlaw Ned Kelly (Main picture: Grenrowan, 1946).

Talk, for the first time, of an Australian tradition began with the Australian Impressionists who worked out of doors. Tom Roberts’ A Break Away, 1891, shows a quintessentially Australian scene of stampeding sheep in a parched landscape being rounded up by a heroic, horse-riding stockman. Modernity was to be summed up in the honed and architectural renderings of the building of Sydney Harbour Bridge that, after the Great Depression, became a symbol of hope for many. Some, such as Margaret Preston, did display in her landscapes a sensitivity to indigenous art, while others, such as Sidney Nolan, began to create new Australian narratives through the use of folklore and local legend, as in his famous series based on the Irish-Australian outlaw Ned Kelly (Main picture: Grenrowan, 1946).

As elsewhere, the 1960s and 1970s in Australia were broad-ranging and eclectic. This was a period of internationalism informed by self-evaluating texts written by the likes of the art historian and cultural critic, Robert Hughes. Formal aesthetic concerns emerged in Fred Williams’s flat afocal landscapes with their textured surfaces. Art also became political and feminist icons such as Tracey Moffat explored attitudes to race and violence. Younger artists, like artists everywhere in the developed world, have embraced multi-media. The exhibition includes photos, sculptural installations and videos. Disorientation is a common postmodern state and Rosemary Laing places an upside-down, horizontally askew house in the landscape, ironically playing with the idea that Australia is "down under", while Fiona Foley’s seductive video, Bliss, shows fields of swaying poppy, as a critique of the hidden history whereby settlers paid indigenous people not in cash but, cynically, in narcotics.

Visual art has been strong in Australia for more than 40,000 years and Aboriginal art still remains the most potent art form on the continent. But visual art was also developed by the settlers and over the last 200 years has come to tell the story of their “wilful lavish land”, not only to themselves but to the rest of the world

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment