Jean Cocteau: 'A poet can never die' | reviews, news & interviews

Jean Cocteau: 'A poet can never die'

Jean Cocteau: 'A poet can never die'

Cocteau, the Jacques of all trades and master of all, died 50 years ago today. He can still astonish

Jean Cocteau, who died 50 years ago today, was a poet/novelist /playwright /film director/designer/painter/stage director/ballet producer/patron/myth-maker/friend of the great/raconteur/wit. A Jacques of all trades and master of all. “Etonne-moi!” (“Astonish me!”) were the words with which Sergei Diaghilev, founder of the Ballets Russes, challenged Cocteau. The result was the ballet Parade (1917), designed by Pablo Picasso, composed by Erik Satie, and set to a scenario by Cocteau.

It is difficult to isolate the films Cocteau directed and/or wrote from his work in other art forms (Londoners can compare his magnificent murals at the Notre Dame de France church off Leicester Square.) Films were just another form of poetry, and the poet at the centre of his oeuvre, ie himself.

Beauty is slightly disappointed when the Beast turns into his young, romantic self

Cocteau made his first film when he was 41 and already famous. The Blood of a Poet (1930) contains all the signs and symbols of the personal mythology evident from his poems, novels, plays and drawings. The death and resurrection of a poet (Orpheus), the link between death and youth (beautiful young men), tauromachy, living statues, opium (of which he was a constant user) and the passing to the other side of the mirror.

Thanks to the patronage of the Vicomte de Noailles, Cocteau was free to experiment with film, exploring the creative process in arresting dream-like images. Although surrealist in manner, The Blood of a Poet (see clip below) was too calculated and conscious to be considered as such by André Breton, surrealist supreme, though Cocteau wrote: "It is often said that The Blood of a Poet is a surrealist film. However, Surrealism did not exist when I first thought of it." The film was a great influence on the American avant-garde, particularly on Kenneth Anger.

Orpheus (1950) is a perfect marriage of Greek myth and Cocteau’s own, and although it uses reverse slow-motion and negative images to suggest the Underworld (reached through the looking glass), the modern-day domestic life of Mr and Mrs Orpheus is filmed “realistically”, elaborating the theme of the poet caught between the worlds of the real and the imagination. “You've never seen death?” says the angel Heurtebise (François Périer). “Look in the mirror every day and you will see it like bees working in a glass hive.”

In Beauty and the Beast (1945, pictured below right), a fairy tale for children and intelligent adults, Cocteau stated that he discouraged his cinematographer, Henri Alekan, and the brilliant art director Christian Bérard from virtuosity in order to show “unreality in realistic terms”. Thankfully virtuosity is evident everywhere in the magical scenes in Beast’s castle. The beast is played touchingly by Jean Marais, behind extraordinary makeup. In the end Beauty is slightly disappointed when he turns into his young, romantic self. Marais, Cocteau’s primo uomo and one-time lover, whose profile Cocteau used for his drawings of Greek heroes, starred in all the films that Cocteau directed or wrote, with the exception of The Blood of a Poet.

The Eagle Has Two Heads (1947) and Les parents terribles (1948) were clever transpositions of Cocteau’s plays to the screen. However, though his cinematic sense prevented them from looking stagey, these wordy and overripe melodramas were happier behind a proscenium arch. Nevertheless, the use of close-ups enabled the director "to catch my wild beasts unawares with my tele-lens".

The Eagle Has Two Heads (1947) and Les parents terribles (1948) were clever transpositions of Cocteau’s plays to the screen. However, though his cinematic sense prevented them from looking stagey, these wordy and overripe melodramas were happier behind a proscenium arch. Nevertheless, the use of close-ups enabled the director "to catch my wild beasts unawares with my tele-lens".

Although directed by others, Cocteau’s presence is strongly felt in other adaptations of his works. Les enfants terribles (Jean-Pierre Melville, 1950), based on his claustrophobic 1929 novel of sibling love, was shot entirely on the stage of the Théâtre Pigalle. Melville’s severe style and craftsmanship, combined with the bejewelled prose, retained much of the strange atmosphere of the original. Roberto Rossellini directed Anna Magnani in a film version of Cocteau’s monodrama La voix humaine (The Human Voice, 1948), and Jacques Demy shot Le bel indifférent (1957) from the 1940 one-act play, written for and starring Édith Piaf (coincidentally, Piaf died on the same day as Cocteau.)

L’éternal retour (Jean Delannoy, 1943) – Cocteau's original screenplay, updating the Tristan and Iseult legend – had two lovers (Marais and Madeleine Sologne) falling hopelessly in love as a result of a love potion issued to them by a vicious dwarf, and eventually finding their apotheosis in death. There is something a trifle ludicrous about the liebestod in the context of "modern youth" in ski jerseys, apparel that became fashionable because of the film’s huge success in France. Made during the Occupation, its blond Aryan lovers were extremely pleasing to the occupiers.

Cocteau’s attitude to the Nazis can be described generously as ambivalent. He fraternised with Germans and was an admirer and friend of Hitler’s favourite architect Arno Breker. This helped him to have his plays and films produced, although much of his art was considered decadent, and he was known to be homosexual. However, Cocteau did all he could to save Max Jacob, the Jewish-born Catholic convert writer, from being sent to a concentration camp, to no avail.

Cocteau’s attitude to the Nazis can be described generously as ambivalent. He fraternised with Germans and was an admirer and friend of Hitler’s favourite architect Arno Breker. This helped him to have his plays and films produced, although much of his art was considered decadent, and he was known to be homosexual. However, Cocteau did all he could to save Max Jacob, the Jewish-born Catholic convert writer, from being sent to a concentration camp, to no avail.

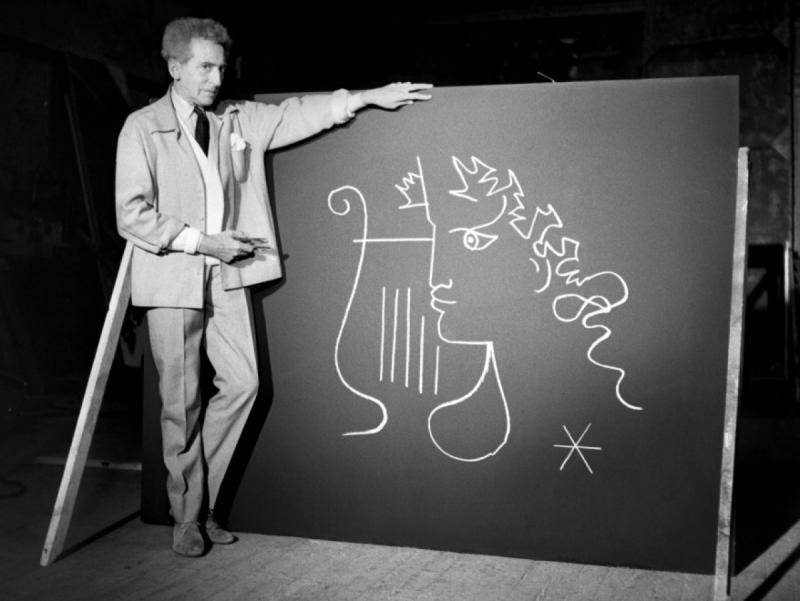

The third of Cocteau's Orphic trilogy, The Testament of Orpheus, his valedictory film, is a self-indulgent, self-mocking self-portrait, with references to his other films, writings and life. He himself wanders through the film (pictured above left), his feet hardly touching the ground, explaining his art with the help of friends (Picasso, Yul Brynner, Marais, Édouard Dermithe, his adopted son, etc.) But, as Cocteau commented, "a film, whatever it may be, is always its director’s portrait." Here, he is penetrated by a sword, but pops up from his grave uttering the words: "A poet can never die." Cocteau’s body died in October 11,1963, but his art lives on.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

London Film Festival 2025 - a Korean masterclass in black comedy and a Camus classic effectively realised

New films from Park Chan-wook, Gianfranco Rosi, François Ozon, Ildikó Enyedi and more

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

After the Hunt review - muddled #MeToo provocation

Julia Roberts excels despite misfiring drama

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

Ballad of a Small Player review - Colin Farrell's all in as a gambler down on his luck

Conclave director Edward Berger swaps the Vatican for Asia's sin city

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - Bradley Cooper channels John Bishop, the Boss goes to Nebraska, and a French pandemic

... not to mention Kristen Stewart's directing debut and a punchy prison drama

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

London Film Festival 2025 - from paranoia in Brazil and Iran, to light relief in New York and Tuscany

'Jay Kelly' disappoints, 'It Was Just an Accident' doesn't

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Iron Ladies review - working-class heroines of the Miners' Strike

Documentary salutes the staunch women who fought Thatcher's pit closures

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

Blu-ray: The Man in the White Suit

Ealing Studios' prescient black comedy, as sharp as ever

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

The Woman in Cabin 10 review - Scandi noir meets Agatha Christie on a superyacht

Reason goes overboard on a seagoing mystery thriller

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

London Film Festival 2025 - crime, punishment, pop stars and shrinks

Daniel Craig investigates, Jodie Foster speaks French and Colin Farrell has a gambling habit

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

I Swear review - taking stock of Tourette's

A sharp and moving tale of cuss-words and tics

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

A House of Dynamite review - the final countdown

Kathryn Bigelow's cautionary tale sets the nuclear clock ticking again

Add comment