theartsdesk Q&A: Writer David Storey, pt 1 | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Writer David Storey, pt 1

theartsdesk Q&A: Writer David Storey, pt 1

The playwright on rugby league, Lucian Freud's dog and bashing Billington

David Storey, who has died at the age of 83, was the last of the Angry Young Men who, in fiction and drama, made a hero of the working-class Northerner.

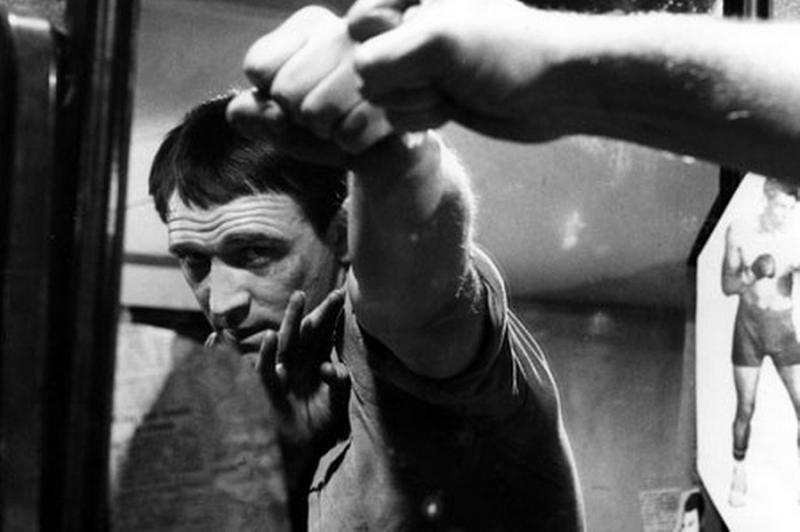

He remained resolutely best-known for This Sporting Life (1960), his debut novel set in the gritty world of rugby league which three years on was made into a groundbreaking film starring Richard Harris. It was partly autobiographical: Storey is the only Booker-winner to have studied human nature in the Leeds second row. As a young man he aspired to be a painter. By commuting for a year between art school in London and rugby club in Leeds, Storey fashioned for himself a life of a double exile in which no one at either polarity quite understood him. A similar dialogue was to be found in his work as a playwright and novelist – he is one of the very few to have built an equal reputation in both fields.

I spent most of my time trying to get seriously injured

Storey was born in 1933, and brought up in Wakefield where he contrived to pass the 11-plus and attend grammar school. He missed out on the other rite of his generation - National Service - thanks to flat feet.

I interviewed him on three occasions and this two-part Q&A conflates those conversations into a biographical overview. In the second part he talked about his life as a writer: the plays for the Royal Court, the novels, his memories of Gielgud and Richardson in Home, of Lindsay Anderson and Richard Harris. But in this first part, Storey recalled in detail his time as a rugby league professional and a student at the Slade (including a remarkable story about the young Lucian Freud), and the long shadow cast over his life and work by his parents. It concludes with the incident for which Storey remains feared in one quarter and no doubt celebrated in others: the night he physically took on the London theatre critics, reserving his strongest punch for Michael Billington of the Guardian. It must be said that for the brawny, hulking presence, and the big-boned Yorkshire face with the ramrod nose, Storey is a quiet and pleasantly Eeyorish teller of wonderful tales against himself.

Read the second part of theartsdesk Q&A with David Storey

JASPER REES: Did you ever go down a pit?

DAVID STOREY: No, I didn't. I had the opportunity but I didn't take it up. I remember going to the pit and watching them going down.

Did you take up rugby out of guilt that you weren’t underground?

No, it wasn't guilt. It was more practicality. But guilt was connected into it. I had then burned my boats academically and had committed myself to being what I thought was an artist, which my parents thought was a real waste of time. I applied for a job in County Hall in Wakefield and as an architect in Leeds. I got to the interview in County Hall and I never got past the front door. I thought I'll never survive this for five minutes. But I turned up at the interview in Leeds with the architect. We were four floors up and his first question was, “Are you a communist? I can detect a communist when he comes through the front door of this building and we're on the fourth floor.” He looked at the artwork I'd brought, and said after looking at it, “Well, you're not a fucking architect. I think you're an artist,” as though that's the worst thing you could possibly be.

I had no way of earning a living then. I had been working tent-erecting then since leaving school. I was playing rugby union for a local club largely out of guilt, because my parents thought they weren't going to support me but at least I ought to be doing something physical. I was so fit because I was tent-erecting, and it was a middle-class club so I was much fitter than anybody else and I scored a try in every game. It just seemed to fall into my hands; I seemed to lean over and score a try. I had an offer from a rugby league club, Dewsbury, to sign on. It wasn't a good club to join and I think they offered £150, which seemed a lot. My father was horrified when I turned it down. I turned up for my next rugby union game to see my name scratched off the list.

I lost interest then. It became clear that if I wanted to carry on writing I couldn't have a full-time job. Leeds advertised for a full-time player. It suddenly seemed if I could get enough money doing that, I could carry on painting. So I went for a trial and played two trial games and they signed me on for what seemed a lot of money: £1,200, for which I got £400. I would get the second £400 when I was 21. The contract was until I was 32. I only actually got the 400 down and then my father told me he thought they were entitled for half of it. I went out and bought a guitar, a portable gramophone and a bottle of sherry and got absolutely sick drunk on the sherry, never learnt to play the guitar but did keep the gramophone. (Pictured, Richard Harris in This Sporting Life.) I didn't want to go on doing it. It was a horrendous life. I liked the game, and I liked the players, but I just couldn't accommodate what I really wanted to do. I spent most of my time trying to get seriously injured. In fact the seed of Sporting Life came out of cowardice, really. In one game - it all happened in a split second - the ball game to my feet in a scrum, I knew I should pick it up, I knew if I picked it up I'd get kicked in the face, and I paused. My second-row partner was on his way out and his instincts were spontaneous, he just leaned down and picked it up instead of me. And he got kicked in the mouth and his mouth was just a mash of blood and broken teeth. And instead of looking at the guy who kicked him, he looked at me and said, “You cunt.”

I didn't want to go on doing it. It was a horrendous life. I liked the game, and I liked the players, but I just couldn't accommodate what I really wanted to do. I spent most of my time trying to get seriously injured. In fact the seed of Sporting Life came out of cowardice, really. In one game - it all happened in a split second - the ball game to my feet in a scrum, I knew I should pick it up, I knew if I picked it up I'd get kicked in the face, and I paused. My second-row partner was on his way out and his instincts were spontaneous, he just leaned down and picked it up instead of me. And he got kicked in the mouth and his mouth was just a mash of blood and broken teeth. And instead of looking at the guy who kicked him, he looked at me and said, “You cunt.”

But I thought somehow this is a microcosm of my experience there. I could see a whole ream of experiences reeling off behind that I didn't quite know how to connect to other things. By then I was at the Slade. Contractually I couldn't live more than 25 miles from the ground but they gave me special dispensation. It was only one guy, the team manager, who was really keen. He had signed me on, as he told me, to bring intelligence into the game. He thought I was a very intelligent player. I was mainly deployed not to get seriously maimed.

Watch the trailer to This Sporting Life

Could you have played for England?

Nowhere near. I don't think temperamentally I could have coped with going on playing. And I was determined anyway that it was only a means to an end. It sounds very little but at the time my father was earning £600 a year down the pit. The same summer I signed on, the club signed the Welsh rugby union captain, Lewis Jones. He was signed for £6,000. He was a very mature player then. He, like me, didn't know the game. I was appalled by what happened to him, because £6,000 then was a record fee and it aroused the resentment of all the other players - I think, more in the opposing team. He was beaten up. I watched him with staggered awe at the punishment he took. But he was brilliant and he survived and eventually ended up captain of Great Britain, as well as of Leeds.

Did you like rugby players?

I think they were very commendable people. And I was very impressed by them all. I think they were some of the nicest people I ever met. I think that my attitude to it was completely wrong. I wanted to be an artist, a writer and a painter, and I really went to art school in order to have time to write. My father wouldn’t support me there so I played rugby league in order to go to art school in order to learn to write. There's a kind of duplicity involved there.

What did he think of the rugby?

He approved of that because I was connected with the real world at last. He thought art you could do on Sunday afternoons, and that was it, really.

How did you get on with your teammates?

All the problems that were created there I created, not the other players. I think I was regressively aggressive, not positively aggressive. I was aggressive because I felt I was an outsider, I was there under false premises, my heart wasn't in it, so all these things arouse a kind of aggression which was nothing to do with the game and everything with how I perceived myself. The worse the game and the more awful the conditions somehow it seemed to correspond with some negative feeling in me and I got very roused by it. I tended to like a lot of heavy rain, very thick mud and everybody thinking, what a waste of time, I wouldn't be doing it but for the money. That seemed to go well with me, it liberated me in some curious way, and I actually played quite ferociously. You'd have to be a psychologist to work out precisely why.

Did they give you hospital passes?

Yes, the only time I had an opening the ball used to go over my head. Then when there wasn't one I'd get the ball straight away. I think if I were them I'd have taken the same attitude to me as they took. To swan up from London while they were digging coal, or in their factories or mills, and to swan in at weekends to play and then swan off again...

Did you join in the camaraderie?

I didn't, no. The scrum half, he was a very outward-going fellow, very muscular and strong, and he was the very heart and soul, the animation of the changing room, and obscenities flowed out effortlessly. I think his name was Platt. I remember him coming up and saying to me - it was quite strange - "I shouldn't swear, David, if I were you. It's not your character." Coming out of this guy it was a very sophisticated observation, and I was intensely moved, (a) by my disgrace in having let myself down by trying to imitate this nonsense and (b) that this guy could step aside from the very heart of it himself and make this observation. I thought it was the very generosity which I associated with the game.

At the Slade you encountered Lucian Freud. What are your memories of him? He was teaching. He conspicuously didn't teach me. I was playing rugby for the Slade at the time, not with any great distinction. I had made only two games, against Royal College of Art and LSE. We won both matches. It had a significant effect on my life at the Slade. I ended up as president of Slade Society, which was the equivalent of the students' union, and also won a lot of prizes, which I think the football helped to... Freud taught the life class. He would go round the class and go to each easel and he'd come to me and then he'd disappear behind me, and nothing would happen for ages. I thought he'd either completely disappeared or left the room or something, and I turned round and his face was here. Took me out of my fucking wits. He didn't say a word. That happened every occasion so I got the message that somehow he wasn't connecting with what I was endeavouring to do.

He was teaching. He conspicuously didn't teach me. I was playing rugby for the Slade at the time, not with any great distinction. I had made only two games, against Royal College of Art and LSE. We won both matches. It had a significant effect on my life at the Slade. I ended up as president of Slade Society, which was the equivalent of the students' union, and also won a lot of prizes, which I think the football helped to... Freud taught the life class. He would go round the class and go to each easel and he'd come to me and then he'd disappear behind me, and nothing would happen for ages. I thought he'd either completely disappeared or left the room or something, and I turned round and his face was here. Took me out of my fucking wits. He didn't say a word. That happened every occasion so I got the message that somehow he wasn't connecting with what I was endeavouring to do.

When I became president I had to organise the annual Slade dinner which was a rather formal and frightening affair. Distinguished guests were invited from the Arts Council and the art world, including people like Stanley Spencer. It was held in one of the life rooms. He came to me beforehand and said he'd bought a ticket for himself and his wife and his wife couldn't come but would I mind if he brought his dog instead? I saw my role there as being a cunt, basically. I said, “Yes, that's fine”, thinking that'll liven things up. I then forgot about it. There was a pre-dinner formal drinks and I had borrowed evening dress and stuff. We were all gathered in the principal Ian Coldstream’s study with the distinguished guests when the door opened and a fucking great dog came in slavering. And it was choking because there was a rope round its neck. It kept on coming in and the rope kept coming in - just yards and yards of rope. Everybody was standing back from the thing. It was clearly completely out of control.

Eventually at the end of this long rope came Freud. I thought he was doing it on purpose and went up to him and said, “Can you control it?” He said “No” as though that was an absurd question: why on earth are you asking such a ridiculous question? It cleared the room in no time. I didn't realise where Freud was sitting. I sat down at the top table and to my horror Freud was sitting opposite me and sitting next to him was the fucking dog. It was sitting on the chair and when the food was served it was put in front of him and it ate off the plate. And of course no one wanted to say they were stuffy arseholes so no one could complain.

The only thing I could think to say was very Yorkshire

I was a real arsehole at the Slade. It had all gone to my head. Coldstream was putting me up for the Prix de Rome, so there was understandably and correctly a whole contingency who took great exception to this arsehole appearing to be running things. There was quite a feisty group of opposition. They were all sitting at table around this large life room, two floors high, and I noticed fires started on different tables. Again no one wanted to be the first to point out this was a bit too much. Then a member of the staff got up at one of the tables and made a speech about revolutionary art. He was a very fiery character. Then to my horror a guy who hated my guts and with whom I had already had a fistfight stood up and made a speech which started off, “David Storey is a cunt”, and got worse and worse.

Things started getting very active. A woman who I had slighted in a previous escapade picked up a dinner plate and threw it at me across the dinner table. The plate missed me but it hit my female guest, who was the secretary. It hit her on the face, it knocked her out and she fell over still sitting on her chair on the floor, completely unconscious. Coldstream, who had a horror of physical violence, looked across the gap to me and said, “Do something, do something.” So I poured my glass of water on her face and brought her round and then the whole thing got completely out of control.

The most alarming thing were the fires. I had rather forgotten Freud and the dog. I should think he got worried about the dog and took him out. We abandoned the room. There was a dance upstairs and we got everybody up there where there weren't any fires. Anyway, at some point I sent my vice-president downstairs to see if the fires were out and everything was cleared and things were under control. He came back and said there was only one person there. The caterers were gone, they'd had enough. But he said, “There was one person sitting in the room alone, who I recognised as Stanley Spencer. I went up to him and said, 'Are you all right, sir?’ He was holding his hands out like that and he looked up at me and said, “I've just insured my hands for £3,000 and I can't afford to come to this occasion any more. I'm sorry."' And I saw him to the door. That's the last time he ever came. It was about 1955.

When I went down to that room there was an Irish peer, who was one of my co-students, a very eccentric fellow who owned the Emperor of Zog's open-top Mercedes Benz, a huge car with headlights like search lamps. Very exuberant. He was a rather Irish but self-contained fellow but wanted to be very lively. He was standing alone, the room was empty except for him, and he had assembled all the glasses that were unbroken and he was systematically throwing them against the wall. There was a great mound of broken glass. I went up to him and the only thing I could think to say was very Yorkshire, “You know you're going to have to pay for all that.” He said, “I know.”

At three o'clock that morning there was a phone call from Professor Coldstream. He said, “I just want to tell you, Storey, before I change my mind, that I've closed down the Slade union and until this terrible element is out of the Slade there will be no more student functions. Although I don't hold you personally responsible.” I was fired from the Slade, asked not to come back, as a result of the year after that. I was in my second year when all this happened. The third year should have been my triumphal year. I got the Slade diploma after three years, and as president of the Slade Society I had automatic preferment of what's called the postgraduate year, which nearly everybody got in in any case. I was the only person in my year not to be given it, with no reason. I was asked not to come back.

Why not?

I had spent the final year writing novels. And my paintings then were so outrageous. They were constructions really, and against the spirit of the place, that they didn't think they could do anything more for me. I had become totally disenchanted with the place.

I had already written the first version of Sporting Life. I did a lot of painting after leaving the Slade and when Sporting Life was accepted I got a huge mass of painting. In my last year at the Slade the then most influential art critic was John Berger and he was asked by the Arts Council to organise an exhibition called John Berger's Looking Forward Exhibition 1956, to be toured by the Arts Council. And he came and picked me out of all the painters at the Slade and took my work. He thought I was one of the coming figures. On the basis of that I did a lot of painting and when the book was to be published I got a one-man show at Zwemmer gallery.

I'd say they were equally balanced at that point. I had done all the painting in this cellar of the sweetshop where we lived in King's Cross, with an overhead bulb, and the gallery guy came and looked at them and was very impressed by them, and we fixed the exhibition to open the month that the book was published. Then he asked just to come back to make a final selection, and said, “Could we look at them in daylight?” So I took them out to the yard at the back, which I'd never done before, and to my horror the colours were completely different. The yellow which looked very mellow and rich under this so-called daylight bulb, looked incredibly acidic and unpleasant. And he lost heart. Initially he said it made no difference and I tried to repaint in the rain in the backyard, but in the end we mutually agreed we'd abandon it. And then I really lost interest. The writing took over in a major way. I just began doing painting whenever I felt like pottering along to do some painting. I never really went back to it. Two or three occasions I did but not for very long.

Your father, who was a miner, gets a lot of attention in the work and the interviews. What influence did your parents have over your life?

He was a dynamic outward-going chap. Very much an extrovert. My mother was a very quiet personality, rather subdued, and had a strong internal life.

Do you inherit as much from her?

I would guess that. Probably the circumstances of the birth, which probably accentuated that. I think she was traumatised because the marriage was difficult. They were both brought up with families with strong religious sentiment but not much religious reality. There was a lot of religious bullshit. My mother was formed by chapel experience, my father by church experience. The result was that when my mother got pregnant before her marriage it seemed like a horrendous mistake so there was a sense of guilt and when the child was born I think they endeavoured to turn it into a perfect phenomenon. It died at the age of six and a half quite suddenly. It was either pneumonia or diphtheria - its lungs were affected. It had had an operation on its lungs without their knowledge in an isolation hospital where it had gone with a fever. It seemed to totally recover - he was a very robust boy and very much like my father - and then just overnight it died.

They went through a very traumatic experience during that night. They experienced a visitation of some sort and subsequent feelings of guilt. My mother became quite suicidal during that period and six months later when I was born they basically got through it by my father persuading my mother that God had taken away one child who had been a guilt-associated child for them, had taken away their mistake, and already here was a replacement. Since I never cried as a baby, I came out totally silent, they saw this as a wonderful golden child. Subsequently looking back I could have been traumatised too. And the reason I was such a pacific baby was that I was locked in there with some kind of indiscernible experience.

Were you mollycoddled?

No, when I was born my mother withdrew emotionally. From what I could gather from her subsequently she very much formalised her responses to me - never cuddled or held me, she said. Because I just lay there in the pram and seemed totally content, they didn't think there was any requirement, in any case. Her self-restraint was endorsed by the baby's behaviour. If you're looking at it in analytical terms you'd say I was born very depressed. Though it didn't seem so to them, and probably not to me.

You were never a father's boy either?

No, he was very avuncular. In many respects he was a child himself. Morally he was in awe of my mother. Her chapel upbringing had quite a profound effect on her. She was the youngest of five children. My father was somewhere in the middle of 13 children. In her the chapel seemed to have bitten deep. My father looked up to her as a moral authority throughout his life.

When my father died it had a very profound effect. But I don't think it was psychological. It didn't lead to depression. He died quite suddenly and I asked to go and see him. After a delay they said I could and I was put into a windowless room and he was laid out on a bier covered with an embroidered cloth and they'd lit four candles and his hands were on his chest, with one eye half-open. And I realised that this was a very profound moment but couldn't verbalise in any way at all. And I asked to see him on my own.

And I just couldn't relate what I was looking at to the living entity. And this half-open eye was quite eerie. There was no glimmer of life beneath it. He used to sleep like that when he came home from the pit. He used to take off his clothes and sit in his underpants and vest and he'd just completely flake out and actually sleep with his eyes wide open. I was never sure he was asleep but he was so exhausted he was. You could pass across and nothing happened in the eyes. I used to be very disturbed by that, largely again with guilt. There was I swanning around painting pictures and clearly he wasn't very well.

Then to my amazement I found that I was walking around the bier like a dog, as though there were something centralised that I couldn't grasp. Then I realised that I was clenching my hands together as I walked round, and then having started it and not noticed I realised that I was saying out loud, "What an earth am I going to do now?" I didn't know why I was saying it. I didn't feel undermined psychically by his death, but it was as if everything had been undermined. So I was astonished by my behaviour and came out quite shattered. The coldness horrified me, and the hardness was just like stone.

This is the last time you'll see me here, because you don't need me any more

I got outside and came home and then heard that there was a spate of deaths and that the cremation would not occur for 10 days. I was then waking up at night very distressed. Inwardly distressed. I would come and sit here [in his sitting room in Kentish town], and it must have been about the third night, I was sitting here, and I had been here for about an hour, and quite racked by his death and what death had become as an abstraction - in other words, what's my death, what's death itself? - and completely pinned in by this and seeing no rationale that would make it acceptable in any way. It was the first time in my life that what was totally unacceptable had to be accepted. And I felt completely powerless.

And at some point my mind had moved on to other things and I was looking in that direction - it was about three o'clock in the morning and the whole neighbourhood was completely quiet, my wife was asleep upstairs - and I was suddenly aware that somebody had come in the door. And then had in fact left the door open. And I looked up and he was standing there. It was quite extraordinary. I didn't feel either frightened, shocked. I felt, it's about time you've come, kind of thing.

He went and he sat there and he was dressed as I'd last seen him in non-hospital attire. I said aloud, “If you are real, make yourself as real as that” and held out my hand. And his voice came back and said, “If you can see me as you see me now why should I make myself as real as that?” I couldn't think of any answer to that. And he sat there for an hour and said, “My life has been distressing but it is at an end, the pain has gone and I'm happy.” Clearly it was a projection but it had caught me quite spontaneously unaware. It stayed there an hour and had this very powerful reassuring effect. And then it faded. I lost it. I talked, mainly about pain and distress. It was a very powerful sense was that any suffering on his part was at an end and that I therefore need not suffer any more.

And then the following night I came down, and always at the moment where I was thinking of going back to bed or not thinking about it, he would reappear, but each time he'd be younger. Through a series of nights he went from the age when he died through to the period when I first knew him as a child. Each time there was a conversation about his life. And then he began appearing as a figure before I'd known him. Ended up as a little boy sitting there, and was very clearly delineated. I could see the holes in his pullover, I could see his nose needed blowing. There was a scar on his knee.

And the final night there was a wooden cradle painted sea green with an ogive-shaped headboard with a pink line painted just inside the perimeter. And his voice said, “This is me on the first Christmas on the first year of this century.” In fact he was born two days before Christmas in 1900. I somehow felt that that was a completion. It didn't come again, there was the cremation and that was it.

Did you find yourself coming downstairs in order to have this vision?

Curiously I didn't, no. I knew something quite powerful was going on. But each time I came down was simply because I couldn't sleep. The last time I woke up two or three months after his death and he was standing like he'd been there at the foot of the bed in his work clothes, when he was about 50 or late 40s. And he said, “This is the last time you'll see me here, because you don't need me any more.” Not resentfully, but just definitively. That's the end of it. And then went. I tried to get him back but nothing would come back.

Did you tell your mother?

Yes.

What did she say?

She said, “Well, I haven't heard anything.” And the last farewell was ages later. I discovered that one of my brothers was going to arrange the disposal of the ashes, and I discovered that they hadn't been, so I went and collected them and then drove up to Yorkshire, to Scarborough in fact, and kept getting to the point of turning back because it was torrential and there was flooding and I thought this is signalling me not to do this. But I kept on. I crossed the Yorkshire border and suddenly the sun came out with all radiance ahead. And I thought, this is the right thing.

I took the ashes to a hill overlooking the village where they lived in retirement and from the top of it you could see out to the North Sea and inland you could see the village. And I poured the ashes on a stile - it came out in a mound - and there was a very thin sea breeze blowing and it blew the ashes off invisibly. The mound imperceptibly became smaller and smaller, and then I realised if I looked at the sun I could see a long thin arc of ash going over the brow of the hill, like a huge wing. Very thin filament of grey ash. Very striking. Until it had all disappeared.

And I thought, well that's it. I had taken me four hours to drive up from London. I got back in the car, thought I'd go and get a meal in Scarborough, but didn't think I could eat anything, so I started driving back. And the sun was beginning to set on the right-hand side of the road. I came back by the A1. I was aware that he was sitting next to me, and when I looked across he was sitting there in his outdoor clothes in his old age and looking ahead. He never spoke. I kept on saying to him, “What have you got to say to me?” Out aloud, and nothing happened, no expression, nothing. I got all the way back to London, pulled up outside and this vision was still very powerfully there and he was still looking forward and he had a flat cap on. I said, “Aren't you going to say anything to me?” And he just turned to me and smiled and didn't say anything at all. And then it all disappeared. And I've never seen him since.

Why were you close to him?

I think my introspective nature identified very much with his outward-going nature. My two brothers were very much outgoing like him, so they would very much have seen an endorsement of themselves. Whereas I saw a dialectic, that there was an activity that wasn't necessarily me.

How long did your mother outlive him?

She died four or five years later. In fact it was a relief. I persuaded the hospital in the end to try and ease her out. She was then quite gone, really.

Did you parents ever see your most autobiographical play, In Celebration?

I don’t think they saw it. They may have read it. My mother came down once with my father to see The Changing Room and was so disgusted by the naked men that she said she never wanted to see another play by me, it was such an embarrassment, in case there were naked figures in it. There was in Life Class of course so she’d have been even more disgusted. My father came down for Home to see it and I introduced him to Gielgud after the play and the total incomprehension on both sides was sort of almost elemental. The miner who had been down the pit for 40 years meeting an actor who was supposedly homosexual and effete. They were two human beings that couldn’t possibly encounter each other at all in any circumstances, I thought.

How much of a clout did you give to Michael Billington?

I knocked his glasses across the floor, and I thought, this is a bit cowardly, really, a man with glasses who doesn’t really mean any harm. I just remembered his first sentence of his review [of Mother's Day], which only had two words in it. It just said, "A stinker." He was very good about it. He came to do an interview not long afterwards and he rang the doorbell and I opened it and he was standing there with a big man beside him and he said, "This is my chauffeur, he’s just come in case there’s a bit of trouble." He’s always been very supportive apart from that one incident.

Do you regret the way that story has followed you around?

Well, it’s fairly ridiculous. Other writers tell me it’s what they’ve always been dying to do but never actually got round to. But it was a freak. The whole production was plagued by bad luck. The designer committed suicide, his replacement had a nervous breakdown and was taken to a mental hospital, the third guy who turned up – I met him in the street afterwards in Belsize Park and said, "Do you live round here?" He said, "No, I’m working round here." I said, "What, the Hampstead Theatre?" He said, "No no, I’m a roofer actually. I do tiling." I thought, Christ, that sums up the play really.

In the previews there were queues for returns and it all went superbly well. On the first night just the whole ethos was quite the reverse for some reason. In the main speech, which is incredibly obscene in the middle of the play, the actor panicked and dried.

It was Alun Armstrong who had to say fuck 25 times in the speech?

Something like that. Very good actor. And it went down. The next night the director had become ill doing it and then had discovered he’d got pancreatic cancer and really was ill, and I’d had to take over to some degree. So I called the cast into the bar at the Court to tell them the reviews were the kind of reviews the Royal Court used to relish because we were against all this stuff. And I was standing on the steps leading up to the door leading up to the Theatre Upstairs and ended my speech and said, "Let’s go and fight."

And I turned and there was the Sunday Times critic. I’ve forgotten his name now. I thought, Christ, and then I looked over his shoulder and there was another critic I recognised, and there was a whole file of all these critics who’d panned the play, including Billington. And I said, "I’m terribly grateful you’ve come to apologise." He said, "No, actually you’re blocking the door to the Theatre Upstairs. There’s a first night there and we can’t get through." I said, "Oh fucking hell." I stepped aside and they all went through and I just couldn’t resist, because they went in single file. I started verbally abusing them and by the time I got to Billington I got really carried away and then went down the line after him and ended up with Irving Wardle.

I felt genuinely for several moments that they had come to apologise, they had all realised the error of their ways and they’d rung each other up and said, "Let’s all go and say we’re terribly sorry." But no such thing had occurred at all, and I thought, aren’t they bastards standing listening to me give this speech about their reviews without saying anything? I’d noticed figures accumulating at the side but hadn’t noticed who they were.

You didn’t really hit them that hard though, did you?

I think I did hit hard at Billington but each blow got less and less. It was on the back of the heads, reproachful, like you do with schoolchildren. You idiot. I remember with Billington I did several because I hit him each time I came to a vowel. Id-i-ot. No, it was a kind of nonsense. The sort of hysteria that happens in the theatre.

Do you go back up to Wakefield?

There are two Wakefields. There's an imaginary Wakefield and there's a real Wakefield which horrifically I see when I get there. And the two are increasingly separated. When I go back although I prepare myself, I know it's going to be a shock, but what's there now has this rather frightening resemblance to what used to be there but isn't what it was.

Do you think of yourself as a Londoner?

No, I feel more like a displaced person, but I don't feel I belong anywhere particularly. Which I rather liked. It was a great relief to get to London. The anonymity is what I've always cherished. I feel a sense of remoteness.

You don't want to be too anonymous.

I don't want to be totally unknown. I want to be anonymous. There's an uneasy balance between the two. But I think I've gone past that.

Past what?

Caring.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment