theartsdesk in Florence: Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Florence: Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino

theartsdesk in Florence: Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino

The Palazzo Strozzi explores the diverging paths of Mannerism. With only one winner

Sadly, the name may not mean much. Jacopo Pontormo is a Florentine painter whose fate it was to come of age in the years after the high tide of the High Renaissance. Its vast shadow has left him languishing in second-division obscurity. Every day in Paris thousands of tourists turn their backs on his Madonna and Child with Saints to gawp at the Mona Lisa. No one visiting Florence lingers in front of his Venus and Cupid, c. 1533 (pictured below) in the same room as the statue of David. The National Gallery has stuck its small stash of Pontormos in a little side room. He has the Mafia to thank for his splashiest moment in the sun: weirdly, a reproduction of one of his most captivating works (main image) hangs in the bedroom of Tony Soprano.

But then Pontormo, by common consensus, is weird. Vasari, the biographer of the Renaissance, depicted him as an eccentric outsider with odd habits and no social graces. His diary, recording mostly his austere eating habits in old age, seems to corroborate this testimony. Freud, who was drawn to write about Leonardo, would have had a field day with Pontormo’s Visitation, not to mention his most famous painting of all, the ravishing but baffling Deposition which hangs in Santa Felicita very near the Ponte Vecchio. (It’s behind bars, which somehow says it all.) But Freud didn’t know about Pontormo. No one did. He is barely mentioned by anyone for the 350 years after his death in 1557. Then around a century ago he was rediscovered. That was when the age of Modernism chanced upon the sheer strangeness of his religious visions, with their veiled air of imminent fracture and emotional instability, and embraced him as a prophet foretelling its own psychic traumas and obsessive compulsions. Yes, his paintings are beautiful (witness the lovely Corsini Madonna and Child with St John the Baptist), and beauty is mostly what people want from the Florentine Renaissance. But he is something else besides: complicated, worrying, unfathomable. His bodies are freakish, his faces exude pain, his colours are explosive and illogical. You feel in paintings such as his Penitent St Jerome, 1529 (pictured below right. Hannover, Landesmuseum) that, for the first time in Florence’s rich history, you are witness to an expression of personal feeling that goes beyond faith, that he was stealthily and perhaps unconsciously forever painting himself. The long and the short of it is that Pontormo’s affronting anxiety doesn’t sell T-shirts and those other branded knick-knacks that power Florence’s tourist economy. It’s really only art historians, parsing brushstrokes and fixated on iconography but less interested in scoping the works for emotional content, who give him their undivided love.

Yes, his paintings are beautiful (witness the lovely Corsini Madonna and Child with St John the Baptist), and beauty is mostly what people want from the Florentine Renaissance. But he is something else besides: complicated, worrying, unfathomable. His bodies are freakish, his faces exude pain, his colours are explosive and illogical. You feel in paintings such as his Penitent St Jerome, 1529 (pictured below right. Hannover, Landesmuseum) that, for the first time in Florence’s rich history, you are witness to an expression of personal feeling that goes beyond faith, that he was stealthily and perhaps unconsciously forever painting himself. The long and the short of it is that Pontormo’s affronting anxiety doesn’t sell T-shirts and those other branded knick-knacks that power Florence’s tourist economy. It’s really only art historians, parsing brushstrokes and fixated on iconography but less interested in scoping the works for emotional content, who give him their undivided love.

The hope is that that is about to change. The Visitation happens to be the promotional image of a new exhibition at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. There have been attempts to haul him into the spotlight before. The same venue devoted the first major show to him in 1955. The Uffizi put Pontormo at the centre of a study of Mannerism in 1996. This is Pontormo’s latest shot at box-office stardom. In an age of viral marketing, it’s also his best chance yet. In recent years the Palazzo Strozzi has become the go-to space for dynamic exhibitions of Florentine and other art which attract international attention. Its Bronzino blockbuster in 2010 broke all records for the venue. Last year its monumental Renaissance sculpture show found the Louvre, for the first time in its history, going second in a touring exhibition.

The hope is that that is about to change. The Visitation happens to be the promotional image of a new exhibition at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. There have been attempts to haul him into the spotlight before. The same venue devoted the first major show to him in 1955. The Uffizi put Pontormo at the centre of a study of Mannerism in 1996. This is Pontormo’s latest shot at box-office stardom. In an age of viral marketing, it’s also his best chance yet. In recent years the Palazzo Strozzi has become the go-to space for dynamic exhibitions of Florentine and other art which attract international attention. Its Bronzino blockbuster in 2010 broke all records for the venue. Last year its monumental Renaissance sculpture show found the Louvre, for the first time in its history, going second in a touring exhibition.

Bronzino was Pontormo’s faithful pupil whose greater worldliness – and canny skills as a flattering portraitist of the Medici - have granted him a high-profile afterlife. Pontormo too could have more than held his own in a stand-alone show – there are works from near and far which haven’t made it into the building, for whatever reason. His Portrait of a Halberdier, once the most expensive Old Master in the world, is one of the very few works the Getty Museum in Los Angeles will not let off the premises. For those paintings closer by, the Strozzi has published another of its so-called "passports", a handy booklet linking the show up to other art works in the city and the region. There’s plenty to choose from around which to build a long weekend (opening times permitting). Herewith a special shout-out for the Palazzo Vecchio's Pontormos - a charming group of little-known wooden panels he contributed to a religious float used in the annual feast of St John the Baptist, the city’s patron saint. He painted them when he was not yet 20. Barring the years of Napoleonic occupation, they remained in use every year until 1872.

Pontormo’s figures are beginning to twist and writhe, Rosso’s to smirk and jeer and flaunt their individualism

But this is not Pontormo’s show alone. He has been required to budge up and share top billing at the Strozzi with his exact contemporary, Rosso Fiorentino. The name may mean even less. It’s perhaps symbolic of their struggle for visibility that neither artist is known by his actual name. Like many Florentines, Jacopo Carrucci da Pontormo took his working surname from the village of his birth. History prefers to remember Giovanni Battista di Jacopo by the colour of his hair. (Imagine Hockney being credited as Yorkshire Blond.)

So, two Mannerists, both alike in anonymity, in fair Florence where we lay our scene. If Pontormo feels cold-shouldered, Rosso was closer to cursed. He was unable to find long-term favour in Florence under any of its swiftly rotating regimes (the Medici were expelled from Florence and returned to power twice). He led a much more itinerant existence, schlepping about Italy in search of commissions. His pitstop in Volterra yielded a mighty Deposition which the Tuscan town's soprintendenza has, for its own motives, refused to lend. He eventually found favour in the French court at Fontainebleau, where he died in 1540.

Still, there is a rationale to their coupling. Both artists were born in 1494, and both joined the workshop of Andrea del Sarto under whose wing they created frescoes for the cycle in the fore-cloister of the church of Santissima Annunziata. Three lunettes by the artists – all freshly conserved with ostentatious colours and ghostly background shapes now coming up a treat - are in the first room of the exhibition. Neither pupil was more than 18, but already you can feel their determination to wriggle out from the High Renaissance yoke. Pontormo’s figures are beginning to twist and writhe, Rosso’s to smirk and leer and flaunt their individualism.

This hunt for an alternative to classical perfection was what became known as Mannerism or, more diagnostically, the Mannerist crisis. The term derives from Vasari’s disapprobation of Pontormo’s loopy so-called “maniera”. The exhibition’s curators argue that, beyond a catch-all label for an era, the word has scant usefulness. Setting these painters side by side would seem to back that up. They had the same start in life and each fell under the influence of Dürer, whose woodcuts turned young Italian heads with stark images of German hyper-realism in the era of Lutheran threat. Not that either was a closet Protestant. The curators also contend that they must surely have travelled to Rome in Andrea del Sarto’s train and seen with their own eyes the revolutions in form and colour freshly daubed by Raphael and Michelangelo (although there isn't any documentary proof).

This hunt for an alternative to classical perfection was what became known as Mannerism or, more diagnostically, the Mannerist crisis. The term derives from Vasari’s disapprobation of Pontormo’s loopy so-called “maniera”. The exhibition’s curators argue that, beyond a catch-all label for an era, the word has scant usefulness. Setting these painters side by side would seem to back that up. They had the same start in life and each fell under the influence of Dürer, whose woodcuts turned young Italian heads with stark images of German hyper-realism in the era of Lutheran threat. Not that either was a closet Protestant. The curators also contend that they must surely have travelled to Rome in Andrea del Sarto’s train and seen with their own eyes the revolutions in form and colour freshly daubed by Raphael and Michelangelo (although there isn't any documentary proof).

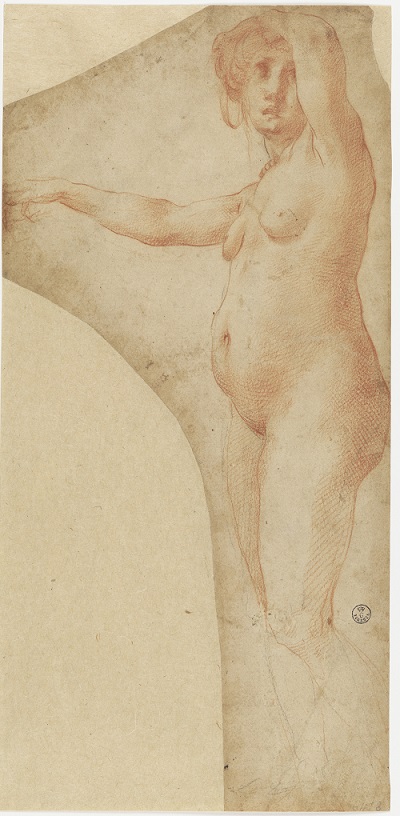

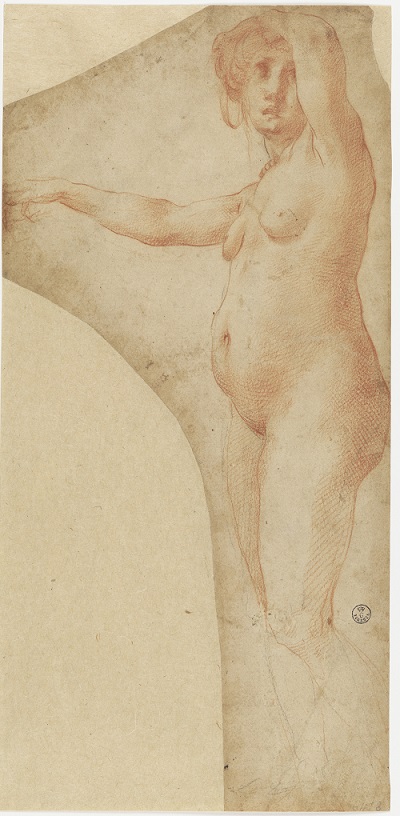

But mostly these two artists would go their separate ways - along private tangents, up blind alleys and down narrow culs-de-sac. The diverging paths invoked by the exhibition’s subtitle are less manifest in rooms devoted to drawings and portraits. Rosso’s sketch of a nude (arguably pregnant?) woman, 1521-2 (pictured above right. Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi) feels very close in spirit to Pontormo’s many wild visions in chalk. Most dramatic of all is the British Museum’s wonderful self-portrait in which Pontormo’s foreshortened painting arm zooms out towards the viewer. (For more Pontormo drawings, best get to Madrid, where currently there is an exhibition of them.)

Meanwhile portraits for individual clients find both artists downplaying their personal quirks. Rosso’s images of doughty black-clad worthies all look vaguely identikit. Pontormo too reins in his natural tendency to see his own anxieties reflected in every sitter’s eyes. His Portrait of a Bishop, 1541-2 (see gallery overleaf), splendidly bearded, is one of the very few works to survive from his last 25 years, which were largely devoted to grand projects for the Medici.

Nonetheless, as the exhibition progresses the differences are laid out, and the comparison feels very much in one artist’s favour. Where Pontormo’s strangeness is always alluring, Rosso’s grows ever more alienating. Where one never loses sight of human gracefulness, the other’s austerity and self-absorption are revealed in jagged forms, hectic energy and dark-eyed occlusion. Rosso’s Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro resembles a howling battle of the triangles, while his Marriage of the Virgin (though much lauded by some) feels like about five altarpieces in one. There are great moments with Rosso - his Death of Cleopatra, 1525, thrillingly liaises death with sex. But it’s with Pontormo that every painting feels like an event, a question and an offering. (Pictured above, Death of Cleopatra. Museum Braunschweig, Kunstmuseum des Landes Niedersachsen.)

Nonetheless, as the exhibition progresses the differences are laid out, and the comparison feels very much in one artist’s favour. Where Pontormo’s strangeness is always alluring, Rosso’s grows ever more alienating. Where one never loses sight of human gracefulness, the other’s austerity and self-absorption are revealed in jagged forms, hectic energy and dark-eyed occlusion. Rosso’s Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro resembles a howling battle of the triangles, while his Marriage of the Virgin (though much lauded by some) feels like about five altarpieces in one. There are great moments with Rosso - his Death of Cleopatra, 1525, thrillingly liaises death with sex. But it’s with Pontormo that every painting feels like an event, a question and an offering. (Pictured above, Death of Cleopatra. Museum Braunschweig, Kunstmuseum des Landes Niedersachsen.)

This hunch about Pontormo comes to a head in the penultimate room, where the Visitation – newly restored – awaits. It is difficult to convey the sheer heft of its impact. The Greeting, Bill Viola’s film created for the Venice Biennale in 1995 to mark Pontormo’s 400th anniversary and on show here, has a damn good try (see clip overleaf). It riffs on sisterly bonding and floating femininity. But nothing moves like the painting itself, in either sense: it wallows with emotion and billows with motion. The two expectant mothers Mary and Elizabeth gaze lovingly into each other’s eyes in a fine display of female feeling. So far so traditional. But meanwhile, gazing out at the viewer are two more women, the same figures but somehow different. Unlike their alter-egos, they seem mournfully aware of a future which for their unborn sons will entail a decapitation and crucifixion. But of course nobody knows for sure. That’s Pontormo, the great Florentine enigma who obliges you to shake your head in awe, but also gnaw your nails in worry. No wonder The Sopranos' Mafia capo was in therapy. For everyone else, a session at the Strozzi is indispensable.

Sadly, the name may not mean much. Jacopo Pontormo is a Florentine painter whose fate it was to come of age in the years after the high tide of the High Renaissance. Its vast shadow has left him languishing in second-division obscurity. Every day in Paris thousands of tourists turn their backs on his Madonna and Child with Saints to gawp at the Mona Lisa. No one visiting Florence lingers in front of his Venus and Cupid, c. 1533 (pictured below) in the same room as the statue of David. The National Gallery has stuck its small stash of Pontormos in a little side room. He has the Mafia to thank for his splashiest moment in the sun: weirdly, a reproduction of one of his most captivating works (main image) hangs in the bedroom of Tony Soprano.

But then Pontormo, by common consensus, is weird. Vasari, the biographer of the Renaissance, depicted him as an eccentric outsider with odd habits and no social graces. His diary, recording mostly his austere eating habits in old age, seems to corroborate this testimony. Freud, who was drawn to write about Leonardo, would have had a field day with Pontormo’s Visitation, not to mention his most famous painting of all, the ravishing but baffling Deposition which hangs in Santa Felicita very near the Ponte Vecchio. (It’s behind bars, which somehow says it all.) But Freud didn’t know about Pontormo. No one did. He is barely mentioned by anyone for the 350 years after his death in 1557. Then around a century ago he was rediscovered. That was when the age of Modernism chanced upon the sheer strangeness of his religious visions, with their veiled air of imminent fracture and emotional instability, and embraced him as a prophet foretelling its own psychic traumas and obsessive compulsions. Yes, his paintings are beautiful (witness the lovely Corsini Madonna and Child with St John the Baptist), and beauty is mostly what people want from the Florentine Renaissance. But he is something else besides: complicated, worrying, unfathomable. His bodies are freakish, his faces exude pain, his colours are explosive and illogical. You feel in paintings such as his Penitent St Jerome, 1529 (pictured below right. Hannover, Landesmuseum) that, for the first time in Florence’s rich history, you are witness to an expression of personal feeling that goes beyond faith, that he was stealthily and perhaps unconsciously forever painting himself. The long and the short of it is that Pontormo’s affronting anxiety doesn’t sell T-shirts and those other branded knick-knacks that power Florence’s tourist economy. It’s really only art historians, parsing brushstrokes and fixated on iconography but less interested in scoping the works for emotional content, who give him their undivided love.

Yes, his paintings are beautiful (witness the lovely Corsini Madonna and Child with St John the Baptist), and beauty is mostly what people want from the Florentine Renaissance. But he is something else besides: complicated, worrying, unfathomable. His bodies are freakish, his faces exude pain, his colours are explosive and illogical. You feel in paintings such as his Penitent St Jerome, 1529 (pictured below right. Hannover, Landesmuseum) that, for the first time in Florence’s rich history, you are witness to an expression of personal feeling that goes beyond faith, that he was stealthily and perhaps unconsciously forever painting himself. The long and the short of it is that Pontormo’s affronting anxiety doesn’t sell T-shirts and those other branded knick-knacks that power Florence’s tourist economy. It’s really only art historians, parsing brushstrokes and fixated on iconography but less interested in scoping the works for emotional content, who give him their undivided love.

The hope is that that is about to change. The Visitation happens to be the promotional image of a new exhibition at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. There have been attempts to haul him into the spotlight before. The same venue devoted the first major show to him in 1955. The Uffizi put Pontormo at the centre of a study of Mannerism in 1996. This is Pontormo’s latest shot at box-office stardom. In an age of viral marketing, it’s also his best chance yet. In recent years the Palazzo Strozzi has become the go-to space for dynamic exhibitions of Florentine and other art which attract international attention. Its Bronzino blockbuster in 2010 broke all records for the venue. Last year its monumental Renaissance sculpture show found the Louvre, for the first time in its history, going second in a touring exhibition.

The hope is that that is about to change. The Visitation happens to be the promotional image of a new exhibition at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence. There have been attempts to haul him into the spotlight before. The same venue devoted the first major show to him in 1955. The Uffizi put Pontormo at the centre of a study of Mannerism in 1996. This is Pontormo’s latest shot at box-office stardom. In an age of viral marketing, it’s also his best chance yet. In recent years the Palazzo Strozzi has become the go-to space for dynamic exhibitions of Florentine and other art which attract international attention. Its Bronzino blockbuster in 2010 broke all records for the venue. Last year its monumental Renaissance sculpture show found the Louvre, for the first time in its history, going second in a touring exhibition.

Bronzino was Pontormo’s faithful pupil whose greater worldliness – and canny skills as a flattering portraitist of the Medici - have granted him a high-profile afterlife. Pontormo too could have more than held his own in a stand-alone show – there are works from near and far which haven’t made it into the building, for whatever reason. His Portrait of a Halberdier, once the most expensive Old Master in the world, is one of the very few works the Getty Museum in Los Angeles will not let off the premises. For those paintings closer by, the Strozzi has published another of its so-called "passports", a handy booklet linking the show up to other art works in the city and the region. There’s plenty to choose from around which to build a long weekend (opening times permitting). Herewith a special shout-out for the Palazzo Vecchio's Pontormos - a charming group of little-known wooden panels he contributed to a religious float used in the annual feast of St John the Baptist, the city’s patron saint. He painted them when he was not yet 20. Barring the years of Napoleonic occupation, they remained in use every year until 1872.

Pontormo’s figures are beginning to twist and writhe, Rosso’s to smirk and jeer and flaunt their individualism

But this is not Pontormo’s show alone. He has been required to budge up and share top billing at the Strozzi with his exact contemporary, Rosso Fiorentino. The name may mean even less. It’s perhaps symbolic of their struggle for visibility that neither artist is known by his actual name. Like many Florentines, Jacopo Carrucci da Pontormo took his working surname from the village of his birth. History prefers to remember Giovanni Battista di Jacopo by the colour of his hair. (Imagine Hockney being credited as Yorkshire Blond.)

So, two Mannerists, both alike in anonymity, in fair Florence where we lay our scene. If Pontormo feels cold-shouldered, Rosso was closer to cursed. He was unable to find long-term favour in Florence under any of its swiftly rotating regimes (the Medici were expelled from Florence and returned to power twice). He led a much more itinerant existence, schlepping about Italy in search of commissions. His pitstop in Volterra yielded a mighty Deposition which the Tuscan town's soprintendenza has, for its own motives, refused to lend. He eventually found favour in the French court at Fontainebleau, where he died in 1540.

Still, there is a rationale to their coupling. Both artists were born in 1494, and both joined the workshop of Andrea del Sarto under whose wing they created frescoes for the cycle in the fore-cloister of the church of Santissima Annunziata. Three lunettes by the artists – all freshly conserved with ostentatious colours and ghostly background shapes now coming up a treat - are in the first room of the exhibition. Neither pupil was more than 18, but already you can feel their determination to wriggle out from the High Renaissance yoke. Pontormo’s figures are beginning to twist and writhe, Rosso’s to smirk and leer and flaunt their individualism.

This hunt for an alternative to classical perfection was what became known as Mannerism or, more diagnostically, the Mannerist crisis. The term derives from Vasari’s disapprobation of Pontormo’s loopy so-called “maniera”. The exhibition’s curators argue that, beyond a catch-all label for an era, the word has scant usefulness. Setting these painters side by side would seem to back that up. They had the same start in life and each fell under the influence of Dürer, whose woodcuts turned young Italian heads with stark images of German hyper-realism in the era of Lutheran threat. Not that either was a closet Protestant. The curators also contend that they must surely have travelled to Rome in Andrea del Sarto’s train and seen with their own eyes the revolutions in form and colour freshly daubed by Raphael and Michelangelo (although there isn't any documentary proof).

This hunt for an alternative to classical perfection was what became known as Mannerism or, more diagnostically, the Mannerist crisis. The term derives from Vasari’s disapprobation of Pontormo’s loopy so-called “maniera”. The exhibition’s curators argue that, beyond a catch-all label for an era, the word has scant usefulness. Setting these painters side by side would seem to back that up. They had the same start in life and each fell under the influence of Dürer, whose woodcuts turned young Italian heads with stark images of German hyper-realism in the era of Lutheran threat. Not that either was a closet Protestant. The curators also contend that they must surely have travelled to Rome in Andrea del Sarto’s train and seen with their own eyes the revolutions in form and colour freshly daubed by Raphael and Michelangelo (although there isn't any documentary proof).

But mostly these two artists would go their separate ways - along private tangents, up blind alleys and down narrow culs-de-sac. The diverging paths invoked by the exhibition’s subtitle are less manifest in rooms devoted to drawings and portraits. Rosso’s sketch of a nude (arguably pregnant?) woman, 1521-2 (pictured above right. Gabinetto Disegni e Stampe degli Uffizi) feels very close in spirit to Pontormo’s many wild visions in chalk. Most dramatic of all is the British Museum’s wonderful self-portrait in which Pontormo’s foreshortened painting arm zooms out towards the viewer. (For more Pontormo drawings, best get to Madrid, where currently there is an exhibition of them.)

Meanwhile portraits for individual clients find both artists downplaying their personal quirks. Rosso’s images of doughty black-clad worthies all look vaguely identikit. Pontormo too reins in his natural tendency to see his own anxieties reflected in every sitter’s eyes. His Portrait of a Bishop, 1541-2 (see gallery overleaf), splendidly bearded, is one of the very few works to survive from his last 25 years, which were largely devoted to grand projects for the Medici.

Nonetheless, as the exhibition progresses the differences are laid out, and the comparison feels very much in one artist’s favour. Where Pontormo’s strangeness is always alluring, Rosso’s grows ever more alienating. Where one never loses sight of human gracefulness, the other’s austerity and self-absorption are revealed in jagged forms, hectic energy and dark-eyed occlusion. Rosso’s Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro resembles a howling battle of the triangles, while his Marriage of the Virgin (though much lauded by some) feels like about five altarpieces in one. There are great moments with Rosso - his Death of Cleopatra, 1525, thrillingly liaises death with sex. But it’s with Pontormo that every painting feels like an event, a question and an offering. (Pictured above, Death of Cleopatra. Museum Braunschweig, Kunstmuseum des Landes Niedersachsen.)

Nonetheless, as the exhibition progresses the differences are laid out, and the comparison feels very much in one artist’s favour. Where Pontormo’s strangeness is always alluring, Rosso’s grows ever more alienating. Where one never loses sight of human gracefulness, the other’s austerity and self-absorption are revealed in jagged forms, hectic energy and dark-eyed occlusion. Rosso’s Moses Defending the Daughters of Jethro resembles a howling battle of the triangles, while his Marriage of the Virgin (though much lauded by some) feels like about five altarpieces in one. There are great moments with Rosso - his Death of Cleopatra, 1525, thrillingly liaises death with sex. But it’s with Pontormo that every painting feels like an event, a question and an offering. (Pictured above, Death of Cleopatra. Museum Braunschweig, Kunstmuseum des Landes Niedersachsen.)

This hunch about Pontormo comes to a head in the penultimate room, where the Visitation – newly restored – awaits. It is difficult to convey the sheer heft of its impact. The Greeting, Bill Viola’s film created for the Venice Biennale in 1995 to mark Pontormo’s 400th anniversary and on show here, has a damn good try (see clip overleaf). It riffs on sisterly bonding and floating femininity. But nothing moves like the painting itself, in either sense: it wallows with emotion and billows with motion. The two expectant mothers Mary and Elizabeth gaze lovingly into each other’s eyes in a fine display of female feeling. So far so traditional. But meanwhile, gazing out at the viewer are two more women, the same figures but somehow different. Unlike their alter-egos, they seem mournfully aware of a future which for their unborn sons will entail a decapitation and crucifixion. But of course nobody knows for sure. That’s Pontormo, the great Florentine enigma who obliges you to shake your head in awe, but also gnaw your nails in worry. No wonder The Sopranos' Mafia capo was in therapy. For everyone else, a session at the Strozzi is indispensable.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment