10 Questions for Playwright Julian Mitchell | reviews, news & interviews

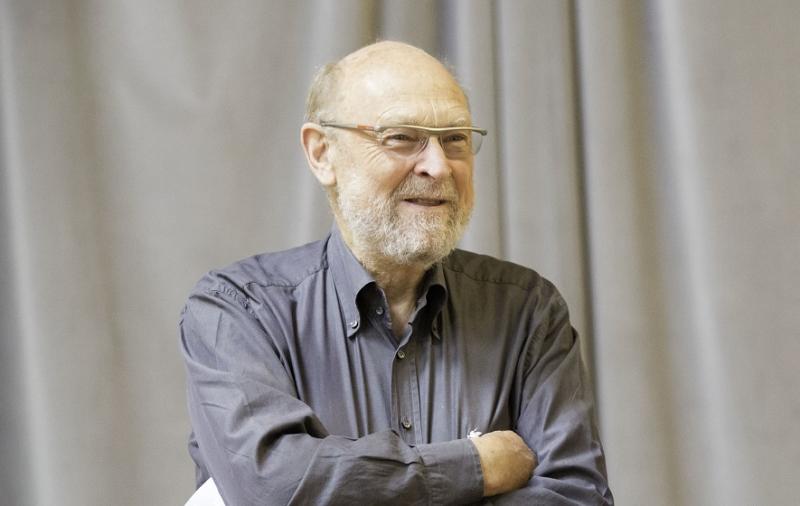

10 Questions for Playwright Julian Mitchell

10 Questions for Playwright Julian Mitchell

The author of Another Country on why it worked then, and still works now

When Julian Mitchell wrote Another Country in a couple of months in 1980, Anthony Blunt had just been exposed as one of the Cambridge spy ring. Donald Maclean and Kim Philby were still living in Moscow and the Cold War had another decade to run. The play was set in a boarding school in which adult authority figures are entirely absent, leaving prefects to run the place like a English establishment.

In the nascent homosexual Guy Bennett and the incipient Marxist Tommy Judd, Mitchell created two roles that would launch a quartet of stratospheric careers. Rupert Everrett (as Bennett) travelled with the original production at Greenwich to the West End. Kenneth Branagh left drama school to join the West End cast as Judd. Bennett was successively played by Daniel Day Lewis and Colin Firth.

Another Country was revived last summat at Chichester Festival Theatre and now makes its way back into the West End for a new generation of theatregoers who will have less urgent memories of Burgess, Maclean, Philby and Blunt. That said, the play’s prevailing themes - sex, class and suicide - are always in theatrical vogue. Julian Mitchell explains to theartsdesk how the play began, and why it carries on. (Pictured below, Rob Callender in Another Country)

JASPER REES: The play was a huge hit in the early 1980s when the notion of betraying the country was still a live issue. What does it have to say to a new generation?

JASPER REES: The play was a huge hit in the early 1980s when the notion of betraying the country was still a live issue. What does it have to say to a new generation?

JULIAN MITCHELL: Of course the Cold War has changed things and communism no longer has any validity for young people, but idealism has not died and what we see now is the extraordinary thing that the idealism has gone into being against our own government. The fear of an Orwellian society has led to idealism being against big government. So there is a relevance there. The other thing that hasn’t changed is teenage attitudes towards gay sex. Although the law has changed for adults, teenagers seem to be extremely hostile to it. One of Stonewall’s big campaigns is to try and do something about bullying in schools. One of the problems for young gays is that, now that it’s all right to be gay if you’re grown up, it means that people are spotted much earlier and therefore subject to really quite serious persecution in some cases.

What was the spark for the play in the first place?

It was the knowing columnists writing about Blunt. He was the coldest lizard I ever met but people loved him. I read all the people like Pincher and were all very knowing and saying, “It was perfectly understandable being a communist in 1930s.” But they didn’t make the connection between the gayness and the treason. It’s quite different wanting to join the Communist party and change the world and wanting to betray your country. They didn’t make that clear. I thought they’d got it wrong and some of them were terribly snooty about gays. One of them wrote about the sad pleasures of sodomy, which was really annoying. And I thought about it and thought I had something to say on the subject. So I wrote it quite quickly, a couple of months.

Guy Bennett would seem to be a fictional version of Guy Burgess. Is that actually the case?

Bennet was a sort of composite. I wish I hadn’t called him Guy but I thought nobody would get the point. Burgess sounds quite a horrible man actually – drunk and dirty and not very attractive – but he was very flamboyant and witty. He always had a fag hanging out of his mouth.

Another Country seems to have had a painless birth but the reality was actually rather different. How hard was it to get it staged?

The play was rejected by absolutely everybody. Most notably by Max Stafford Clark at the Royal Court who asked me for a drink and said, “Of course this is exactly like my school but I don’t see what the play is about.” I was very lucky it was done at all. The National rejected it, the RSC rejected, all commercial managements rejected it. And it was finally picked up by Greenwich.

Can you put your finger on why it was not snapped up?

It was very odd because the audiences got it straight away but the professional readers didn’t. One of the reasons people rejected it was they were all teenagers and therefore there was no name and no parts for women.

The play became a finishing school for a generation of young actors, above all for Rupert Everett. Was it clear from the beginning that he was destined for stardom?

I claim - though I’m sure he would deny it - that I discovered Rupert. Someone said, “You must get these two actors, Julian Wadham and Rupert Everett.” He was at the Citz and he came down and he seemed an absolute natural. Stuart Burge who was directing Another Country wasn’t there that day. The first Judd was another actor and he wasn’t really right for the role. Ken Branagh walked in [to audition for the West End transfer] and again I was the only person there.

How did the three Bennetts bring to the role?

How did the three Bennetts bring to the role?

They were all quite different personalities. Dan Day Lewis brought a greater darkness to it than Rupert did. Colin [Firth] was just a very good versatile actor. I don’t think he was as high-spirited as Rupert. Daniel had a darker quality whereas Colin brought him back more towards the light. Daniel was not so obviously young. (Pictured above, Rupert Everett and Colin Firth in the film of Another Country.)

It remains the best known play of your long career. From this distance what do you make of its monumental success?

You can never tell. It’s so much luck. My next play was totally misunderstood. It was meant to be a metaphor for communist and Stalinist Russia. People thought I’d had a religious conversion and gave it such a kicking and that brought me down to earth pretty suddenly.

The film adaptation came out in due course. Did you find it an easy journey from stage to screen?

The film is really very different. I didn’t know what to do when we came to adapting the play. Whereas in the play in the love object is not seen, you simply couldn’t get away with that in the film. The visit of the uncle, in which a great many of the Bloomsburyish ideas floating around in the play are concentrated, you couldn’t do in the film. Somebody talking about Walter Pater - imagine what they’d make of that in Los Angeles. And so I found it very frustrating in a way.

Was this snapshot of the English establishment based on your own experiences of Winchester?

What I describe in the play is I’m sure right. If you have a really nasty senior prefect the next one will try to be nice. I’ve never forgiven the really awful senior prefects. One of them I’m glad to say electrocuted himself in his own garage. By mistake. When I heard that I rejoiced. A horrible man.

- Another Country at Trafalgar Studios from 26 March

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Winter's Tale, RSC, Stratford review - problem play proves problematic

Strong women have the last laugh, but the play's bizarre structure overwhelms everything

The Winter's Tale, RSC, Stratford review - problem play proves problematic

Strong women have the last laugh, but the play's bizarre structure overwhelms everything

Brixton Calling, Southwark Playhouse review - life-affirming entertainment, both then and now

Nostalgic, but the message is bang up to date

Brixton Calling, Southwark Playhouse review - life-affirming entertainment, both then and now

Nostalgic, but the message is bang up to date

Inter Alia, National Theatre review - dazzling performance, questionable writing

Suzie Miller’s follow up to her massive hit 'Prima Facie' stars Rosamund Pike

Inter Alia, National Theatre review - dazzling performance, questionable writing

Suzie Miller’s follow up to her massive hit 'Prima Facie' stars Rosamund Pike

A Moon for the Misbegotten, Almeida Theatre review - Michael Shannon sears the night sky

Rebecca Frecknall shifts American gears to largely satisfying effect

A Moon for the Misbegotten, Almeida Theatre review - Michael Shannon sears the night sky

Rebecca Frecknall shifts American gears to largely satisfying effect

Burlesque, Savoy Theatre review - exhaustingly vapid

Adaptation of 2010 film is busy, bustling - and bad

Burlesque, Savoy Theatre review - exhaustingly vapid

Adaptation of 2010 film is busy, bustling - and bad

Don't Rock the Boat, The Mill at Sonning review - all aboard for some old-school comedy mishaps

Great fun, if more 20th century than 21st

Don't Rock the Boat, The Mill at Sonning review - all aboard for some old-school comedy mishaps

Great fun, if more 20th century than 21st

The Estate, National Theatre review - hugely entertaining, but also unconvincing

Comedy debut stars Adeel Akhtar, but is an awkward mix of the personal and the political

The Estate, National Theatre review - hugely entertaining, but also unconvincing

Comedy debut stars Adeel Akhtar, but is an awkward mix of the personal and the political

That Bastard, Puccini!, Park Theatre review - inventive comic staging of the battle of the Bohèmes

James Inverne enjoyably reconstructs the rivalry between Puccini and Leoncavallo

That Bastard, Puccini!, Park Theatre review - inventive comic staging of the battle of the Bohèmes

James Inverne enjoyably reconstructs the rivalry between Puccini and Leoncavallo

Till the Stars Come Down, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - a family hilariously and tragically at war

Beth Steel makes a stirring West End debut with her poignant play for today

Till the Stars Come Down, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - a family hilariously and tragically at war

Beth Steel makes a stirring West End debut with her poignant play for today

Nye, National Theatre review - Michael Sheen's full-blooded Bevan returns to the Olivier

Revisiting Tim Price's dream-set account of the founder of the health service

Nye, National Theatre review - Michael Sheen's full-blooded Bevan returns to the Olivier

Revisiting Tim Price's dream-set account of the founder of the health service

Add comment