The Story of Women and Art, BBC Two | reviews, news & interviews

The Story of Women and Art, BBC Two

The Story of Women and Art, BBC Two

Amanda Vickery's mission to rescue female artists from centuries of misogyny

Last year, the German artist Georg Baselitz told Der Spiegel: “Women don't paint very well. It's a fact,” citing as evidence the failure of works by female artists to sell for the massive sums raised by their male counterparts. The amusing punchline to that story is that shortly afterwards a Berthe Morisot painting sold at auction for more than double the amount ever achieved by Baselitz himself. But be honest - come on, use your fingers - how many women artists can you think of?

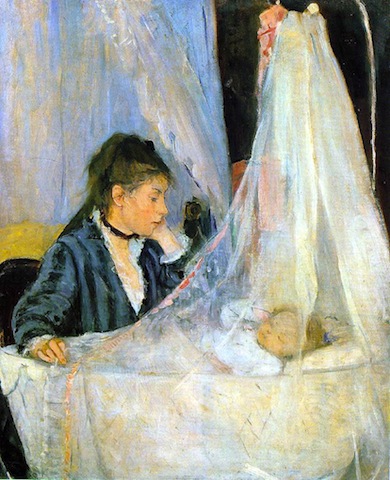

But never underestimate Professor Amanda Vickery, the breathlessly enthusiastic presenter of this new three-part series. Her incredulity at the maleness of Renaissance Italy is terribly hammed up, but in that wide-eyed Nigella Lawson way that can be quite appealing. “Male bodies are everywhere,” she notes, wandering around Florence’s Piazza della Signoria, inspecting a series of sculpted marble penises. “Women are models and muses, but there is an absence of female artists themselves,” she says, amazed. Come on, Amanda, tell us one we don’t know. (Pictured below: Berthe Morisot's The Cradle, 1872)

Vickery’s trump card is that she knows that we think we know what is going on here. But the truth is that those of us who do not believe that women lack the talent to become artists have by and large fallen for a bigger and more pernicious lie, that women artists have barely existed at all, so successfully were they shut out from the male realms of education, training and business.

Vickery’s trump card is that she knows that we think we know what is going on here. But the truth is that those of us who do not believe that women lack the talent to become artists have by and large fallen for a bigger and more pernicious lie, that women artists have barely existed at all, so successfully were they shut out from the male realms of education, training and business.

Vickery jolts us out of our lazy, accepted wisdom with the story of Properzia de Rossi, a woman who in the early 16th century was sufficiently talented and courageous to pursue a career in that most masculine of art forms, sculpture. As a woman, not only was she considered to lack the brainpower to be an artist, but just imagine her poor frail arms struggling with a hammer and chisel. Refused training and materials, and certainly not permitted to study the male nude, she honed her skills by sculpting exquisite scenes from discarded plumstones.

When she won a competition at the Basilica di San Petronio, Bologna, she sealed her own fate: her wonderful marble frieze was simply too good to be tolerated by her male rivals. Without access to male models, how could she possibly understand so thoroughly the contours of a man’s leg, unless she were a woman of questionable morals? Branded a “bitch”, she was driven out of her profession and died in a paupers’ hospital aged just 40. But the most shocking aspect of this story is that even today, Rossi’s finest work remains unacknowledged: hidden in amongst the racks of postcards, her exemplary sculpture is simply ignored.

The great strength of Vickery’s narrative is that she avoids presenting us with a list of victims. For every sad story, she points us to women who held their own, like the court painter Sofonisba Anguissola (pictured left: Anguissola's Self-Portrait Painting the Virgin, 1556) and Lavinia Fontana, who ran a prolific and successful workshop, despite enduring a mind-boggling 11 pregnancies. Not only this, Vickery highlights how women painters took ownership of stock subjects, like the Bible story of Susanna and the Elders, reinterpreting the story from an unmistakably female perspective. In the hands of a woman painter, Susanna is not enjoying the attentions of the older men but recoiling from their lecherous advances.

The great strength of Vickery’s narrative is that she avoids presenting us with a list of victims. For every sad story, she points us to women who held their own, like the court painter Sofonisba Anguissola (pictured left: Anguissola's Self-Portrait Painting the Virgin, 1556) and Lavinia Fontana, who ran a prolific and successful workshop, despite enduring a mind-boggling 11 pregnancies. Not only this, Vickery highlights how women painters took ownership of stock subjects, like the Bible story of Susanna and the Elders, reinterpreting the story from an unmistakably female perspective. In the hands of a woman painter, Susanna is not enjoying the attentions of the older men but recoiling from their lecherous advances.

In the Netherlands of the 17th century, Johanna Koerten used the male-dominated field of portraiture to lend gravitas to her chosen medium, the domestic art of papercutting. Her papercut portrait of William of Orange is so finely worked that it looks like a pen-and-ink drawing, and in her day, Koerten was sufficiently celebrated that a piece of her work commanded a price higher than Rembrandt’s The Night Watch.

Today, of course, Johanna Koerten is unknown, and Vickery’s trip to the Lakenhal Museum in Leiden to see her portrait of William of Orange is a damning illustration of how female artists continue to be ignored. But Vickery is not going to put up with this, and looks unimpressed as she is led into the museum’s basement.

“So where is she then?” The curator sheepishly opens a drawer. Vickery is outraged. “So here she is, the woman that once outsold Rembrandt and you keep her in storage. Well, do you think we could get it out and restore it to pride of place?” The curator is not about to argue, and the next thing we see is the papercut framed and hanging in the gallery, next to a beaming Professor Vickery. Job done.

So how about this for the BBC Arts agenda: Amanda Vickery in a room with Georg Baselitz? Now that would get the ratings up.

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment