Lorin Maazel (1930-2014) on Puccini's Golden Girl | reviews, news & interviews

Lorin Maazel (1930-2014) on Puccini's Golden Girl

Lorin Maazel (1930-2014) on Puccini's Golden Girl

The conductor, who has died aged 84, enthusing in 1991 about a masterpiece

I met one of the 20th century’s most impressive, if not always sympathetic, conductors twice, on both occasions to talk Puccini before La Scala recordings of La fanciulla del West (The Girl of the Golden West) and Manon Lescaut.

Maazel was then still in his grand mastery, and very excited about what he saw as a phenomenal score for the California-set opera. That lit him up. Puccini’s take on Abbé Prévost’s novel, it seems, did not, or maybe he was just in a bad mood. Certainly he wouldn’t be drawn – it was a simple work from the orchestral point of view, he declared, and that was more or less that. I and a journalist from Berlin thought it might be best under the circumstances to share the interview, and his downright rudeness. In the end there wasn’t even enough worth piecing together for a second session report.

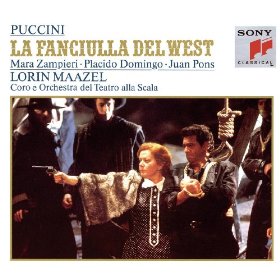

Fanciulla had been different. For a start, there was Domingo (pictured right in Jonathan Miller's Scala production), bringing Juan Pons, the baritone playing the villain, to the brink of tears on stage with Dick Johnson aka bandit Ramerrez’s great aria “Ch’ella mi creda”. Maazel was interesting on those two and a half minutes: "How many other arias can you think of in the key of G flat major? Not one – pure genius! It has that wonderful phrase when he sings of Minnie [the 'girl of the golden west' who saves his life, bartender of the Polka Dot Saloon] as ‘the only flower of my life’. It’s such a lovely idea, think of all those people whose battle for life is so depressing, and then just one moment of beauty may come and illuminate the dark corners of their existence, so that they feel they may have lived just for that one thing."

Fanciulla had been different. For a start, there was Domingo (pictured right in Jonathan Miller's Scala production), bringing Juan Pons, the baritone playing the villain, to the brink of tears on stage with Dick Johnson aka bandit Ramerrez’s great aria “Ch’ella mi creda”. Maazel was interesting on those two and a half minutes: "How many other arias can you think of in the key of G flat major? Not one – pure genius! It has that wonderful phrase when he sings of Minnie [the 'girl of the golden west' who saves his life, bartender of the Polka Dot Saloon] as ‘the only flower of my life’. It’s such a lovely idea, think of all those people whose battle for life is so depressing, and then just one moment of beauty may come and illuminate the dark corners of their existence, so that they feel they may have lived just for that one thing."

It wasn’t only Domingo who sent everyone present at a vintage Scala night wild. The orchestra stamped its approval for Maazel at the end – something that I was told the house hadn’t witnessed over two decades, not even in the case of Riccardo Muti, who was watching with no apparent rancour from a box.

So many of Maazel’s later performances, both live and on disc, seemed lacking in real passion that I think I was lucky to catch one which had it in spades. He wasn’t afraid to use the word “love” in connection with Puccini, and having recorded even the early rarity Le Villi and the much later La Rondine, then rarely heard, he knew what he was talking about. “I’ve been a Puccini fan in a naïve and intuitive way all my life,” he told me. “My father was a singer, and I used to accompany him in all those arias, Bohème and so on. I’ve always been amazed, and continue to be amazed, by the years in which the composer was treated with a certain amount of contempt simply out of jealousy, because he had this marvellous gift for a singable tune.”

He went on to tell me how he himself came to realize that there was more to Puccini than just the “singable tune”. “Tosca was the first of his operas I came to grips with, and what a score! Everything is worked out, every detail of orchestration and balance, and there always seems to be an inner logic to the composition – there isn’t a bar that isn’t absolutely essential. The problem, as I began to discover over the years, doesn’t lie with the composer, it lies with the interpreters and what is expected from the interpreters by people who have dubious taste. I learnt not to confuse sentiment with sentimentality – one is in fact a negation of the other.”

Maazel was awed when he began work on Fanciulla. “After all, you don’t find conductors like Toscanini, De Sabata and Mitropoulos wasting their time on a work they didn’t think worthy of their efforts. It’s tough. Just to run through it is bad enough, I would admire any conductor just for getting through it from first note to last without too many disasters – there’s a pitfall a minute. It’s certainly harder than Bohème or Tosca from a technical point of view. But then to do it well, so that it all sounds extremely natural – so that it flows and sounds effortless – that requires a long preparation, which everyone at La Scala was happy to give it. But once you’ve got there, you don’t have to play down the big moments, or play up the character scenes, because it’s all so perfectly balanced.”

Maazel was awed when he began work on Fanciulla. “After all, you don’t find conductors like Toscanini, De Sabata and Mitropoulos wasting their time on a work they didn’t think worthy of their efforts. It’s tough. Just to run through it is bad enough, I would admire any conductor just for getting through it from first note to last without too many disasters – there’s a pitfall a minute. It’s certainly harder than Bohème or Tosca from a technical point of view. But then to do it well, so that it all sounds extremely natural – so that it flows and sounds effortless – that requires a long preparation, which everyone at La Scala was happy to give it. But once you’ve got there, you don’t have to play down the big moments, or play up the character scenes, because it’s all so perfectly balanced.”

We then plunged into details – how Maazel had discovered over 70 Leitmotifs great and small, how you couldn’t take a second wind player out of the textures without missing it, the importance of the dismal tritones at the ominous beginning of the third act. We ended up discussing the broad brushstrokes of David Belasco’s wild West play on which the opera was based. “Out of context, a lot of it sounds pretty basic by the standards of modern psychology. But if you have an extremely subtle story, how are you going to set it to music? The words and the theatrical element have in a sense taken the musical wind out of your sails. But because Puccini’s story is so bare and elemental, he’s able to create something which is immensely subtle and extremely rich. And the more I conduct it, the more it comes to seem the richest of all his operas."

Overleaf: a YouTube selection of Maazel's performances as conductor - and violinistMaazel in the early 1960s playing and directing the first movement of Mozart's K216 Violin Concerto. Worth it for the spectacular cadenza

The complete Teatro alla Scala recording of La fanciulla del West. Dry live sound, weird Minnie (Zampieri), all else superb

New York Philharmonic recording of the finale to Tchaikovsky's Manfred Symphony

An early Vienna Philharmonic recording of Sibelius's Fourth Symphony from a superb cycle

Finally, New Year's Day froth in Vienna, 1999

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment