Francesca Woodman killed herself at the age of 22, the biographical fact that colours her work and which it is de riguer to mention. She left behind paintings, it is said, as yet publicly unseen, and literally hundreds upon hundreds of negatives and 800 proofs of black and white pre-digital photography. And since that very early death – and early death, whether suicide, accident, disease or murder has been sometimes seen with rabid cynicism as an outstanding career move – she has, over the past two decades, become something of a cult figure. Or rather her imagery has, collected by the grandest, and given prestigious showings (in 2011-2012, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and the Guggenheim, New York). She has been the subject of more books than could fill a shopping trolley, and the 2006 Phaidon monograph has already been reprinted three times.

She was born in 1958 in Denver to artist parents George and Betty Woodman and spent her childhood in Colorado. But the family also spent substantial time in Florence, and many a summer thereafter in their own house in the Tuscan countryside. Francesca went for a year or so to an American equivalent of Eton (Phillips Academy), then Rhode Island School of Design, and was already exhibiting in well known galleries before her death. An international network of leading commercial galleries and public museums now show her work. (Pictured below: untitled, New York, 1979-80.)

The short life was packed with geographical incident and a subtly invidious kind of energy. Much of her photography required almost heroic kinds of physical endeavour, with cameras on the ceiling and a variety in scale. Her main subject is herself, as she put it, always available, where she features in an interior or a wistful landscape. The imagery is non-narrative, except that she intriguingly suggests some kind of story going on beyond the frame of the photograph. It exhibits the kind of self-obsessed poignancy that, say, Duane Michals has made his own, the yearning that infects say Robert Mapplethorpe’s self examination. Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all: in this case the mirror is the camera.

The short life was packed with geographical incident and a subtly invidious kind of energy. Much of her photography required almost heroic kinds of physical endeavour, with cameras on the ceiling and a variety in scale. Her main subject is herself, as she put it, always available, where she features in an interior or a wistful landscape. The imagery is non-narrative, except that she intriguingly suggests some kind of story going on beyond the frame of the photograph. It exhibits the kind of self-obsessed poignancy that, say, Duane Michals has made his own, the yearning that infects say Robert Mapplethorpe’s self examination. Mirror, mirror on the wall, who is the fairest of them all: in this case the mirror is the camera.

Her significance is perhaps partly explained not only by the unprecedented growth of self-absorption, narcissistic yes, but also questioning and even despairing, which is the tenor of our times; the current craze for the selfie at one level, and the continuing search for satisfying relationships with the self – and others – which seems to define our notion of the have-it-all society. That Francesca Woodman was also a beautiful young woman who, however self-consciously, made her own self her chief subject is hardly a disadvantage. It is unclear whether it is deliberate that some of the poses curiously echo the Lautrec and especially Dégas scenes of naked women, prostitutes and brothels, and perhaps especially some of the photographs of the prostitutes of the New Orleans district of Storyville, their wares on display, by the turn of the last century photographer EJ Bellocq. Here in the parlance of feminism women were subjected to the male, even at times misogynist, gaze. (Pictured below: Providence Road Island, 1976)

In Zigzag, though, this compilation does something which gives added depth to Woodman’s images. Yes, there are the usual subjects, Woodman herself and occasionally her female peers also pressed to join her in an unclothed state (and in our airbrushed universe, it is rather unexpected to see unabashed pubic and armpit hair casually displayed, let alone some curiously innocent self examinations). But as the exhibition title indicates the selection underlines the careful almost geometric structure that underlines the seemingly artless, spontaneous groupings of adolescent or twenty-somethings languidly flinging themselves about in contradictory fashion.

In Zigzag, though, this compilation does something which gives added depth to Woodman’s images. Yes, there are the usual subjects, Woodman herself and occasionally her female peers also pressed to join her in an unclothed state (and in our airbrushed universe, it is rather unexpected to see unabashed pubic and armpit hair casually displayed, let alone some curiously innocent self examinations). But as the exhibition title indicates the selection underlines the careful almost geometric structure that underlines the seemingly artless, spontaneous groupings of adolescent or twenty-somethings languidly flinging themselves about in contradictory fashion.

Her father George, one half of the parental guardian of the flame, suggests, of course accurately, that the 1970s were the time of the grid, calling on Mondrian, Judd and Jasper Johns, although curiously not mentioning that king of the line, Sol LeWitt.

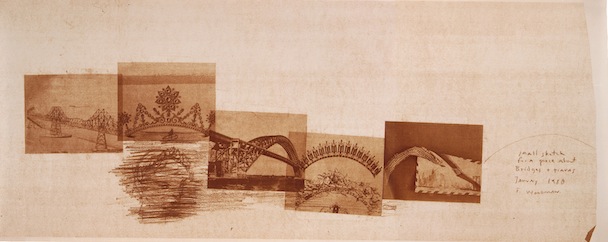

There is a quiet wit: a small piece of five joined images on bridges and tiaras, described as a sketch (pictured below). A linking too called Zigzag Study, New York, of some 13 images of female bodies, limbs, dress collars, all zig-zags, which has a gently subversive humour. You start spotting the zig-zags, arms and legs bent at elbow and knee, in all the other haunting images of Francesca, it turns out, at play. This transforms our sense of the anxiety which has hitherto appeared to infuse most of her photographs, so often seemed to be hinting at a catastrophe just about to happen. This small exhibition, by concentrating on a semi-hidden motif, makes her both a more approachable and more considerable artist than hitherto.

What would have happened is a mystery of course. Had she already peaked? Are these works frozen in aspic, or would going on have led to liberation, an even greater invention, and an imagination which looked to embrace an ever wider world?

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment