Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends, National Portrait Gallery | reviews, news & interviews

Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends, National Portrait Gallery

Sargent: Portraits of Artists and Friends, National Portrait Gallery

Tender feeling and empathy pervade the work of this grand master of the swagger portrait

Oh, Dr Pozzi! This gorgeous man is garbed in a red wool, full-length robe, almost completely obscuring his elegantly gleaming white shirt. The shirt collar frames his face, casting light, and its frilled cuffs emphasise his improbably long-fingered hands in a lively gesture.

The doctor's pose (Portrait of Dr Pozzi, 1881, pictured left) is almost one of 17th-century formality, even theatricality but the costume – is he about to go out or preparing for bed? – adds an undoubted frisson of edgy sensuality, emphasised by the subject’s irresistible glamour.

The doctor's pose (Portrait of Dr Pozzi, 1881, pictured left) is almost one of 17th-century formality, even theatricality but the costume – is he about to go out or preparing for bed? – adds an undoubted frisson of edgy sensuality, emphasised by the subject’s irresistible glamour.

Sargent was prolific – some 600 portraits, not to mention perhaps as many as 1,500 paintings and watercolours of other subjects – and became the artist of choice for the élite in political, intellectual and artistic spheres. An American, he was born in Italy, educated in France, looked like a German, spoke, it was said, like an Englishman, and painted like a Spaniard. He was born in Florence to East Coast America grandees – his father, a doctor, was persuaded by his Europhile wife that he needed to be in Europe for his health. He was to keep his American citizenship all his life although he only paid his first visit to the USA in its centennial year of 1876 when he was already 20.

He was widely travelled, multilingual, a gifted pianist and musician, and as a painter above all influenced by such as Velazquez, for the congnoscenti then just coming back into fashion. He was the grand master of the so-called swagger portrait, commissioned to portray the great and the good of Paris, England and eventually America, from the Vanderbilts to the Rockefellers, the Boston Brahmins to the British aristocracy. His very facility with paint, the wealth of flattering albeit staggeringly skilled society portraits led eventually, posthumously, to a shadow on his reputation, as the avant-garde eclipsed the more traditional, however expert. Sargent seemed perhaps shallow compared to the Impressionists, and to Whistler.

Sargent is supposed to have remarked that every time he painted a portrait he lost a friend

But the great pleasures offered by his sheer captivating skill with paint has led to a reversal of critical fortunes. The huge exhibition in London at Tate Britain in 1998 provided fascinating insights into the ruling élite, and delight in bravura expertise.

This exhibition should persuade even more of us that it is not just the creamy swathes of white paint, the sheen of satin and silk, the softness of a woman’s skin, the uncannily wrinkled neck of the old, that is so beguiling. The commissioned portraits are often but not always psychologically penetrating. But now at the National Portrait Gallery we see in sharp focus an intimate side of the artist’s milieu.

Here is the last of the old masters in a new guise: revealing, affecting, human and humane. Here are the literati, the intelligentsia, the actors, poets, writers, musicians, artists, among whom he moved and in a very real sense had his being. His fellow artists are almost all minor ones, but included here are two formidable geniuses: Rodin and Monet. He was a very close friend of the latter.

Sargent is supposed to have remarked that every time he painted a portrait he lost a friend; but what is remarkable here is the evident empathy and interest, and the persuasive insights. The full-length portrait of the young, and very pale aesthete W Graham Robertson,wrapped up in a huge overcoat – huge hands almost fluttering, an ancient beribboned dog in a basket at his feet – shows a startled sensitivity. The Pailleron children, Edouard and Marie Louise, whose parents were leaders of the Paris salon, evidently had to sit endlessly for the artist. They are beautifully dressed, their expressions wonderfully sulky and resentful, quietly furious, and bordering on mutinous.

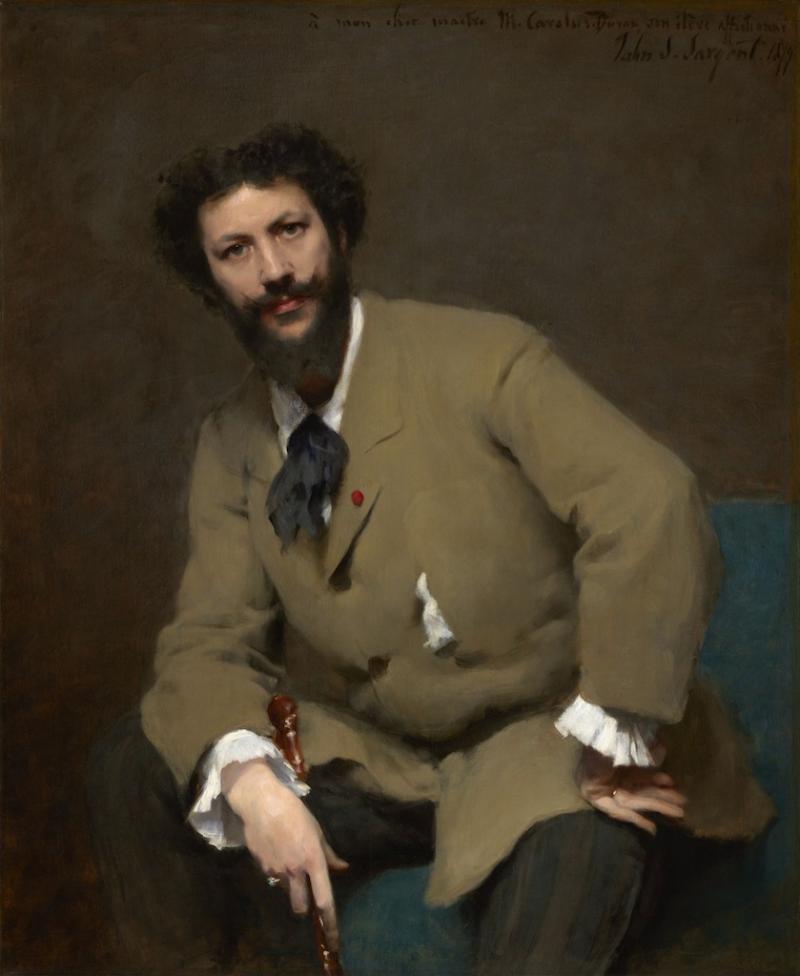

Henry James said he had a knockdown insolence of talent: Sargent’s portrait of his teacher Carolus-Duran, 1879, (main picture) is the painting that inspired the comment, and yet, elegantly languid as the subject is, it seems that the portrait is irradiated with respectful affection and admiration; indeed it is so inscribed by the artist, who was only 24 when he painted this tour de force.

Here too there are homely portraits, of people who seem extraordinarily vivid and alive: his compatriot the artist Charles Stuart Forbes in one such, curiously wet mouthed, gazing out with a quiet determination. His paintings of artists can be quietly if affectionately sardonic. In The Fountain, Villa Torloni, 1907, the American artist Wilfred de Glehn lounges, dozing while his artist wife Jane, perched on a balustrade, paints away, concentrating hard on the garden scene, a contrast to her husband’s studied indolence.

In An Out-of-Doors Study, c.1889, Madame Helleu is patently bored and fed up as she listlessly semi-naps next to her husband Paul, who is totally absorbed as he sketches by the river in the Worcestershire countryside. An Artist in His Studio,1904 (pictured above), shows us the bearded Antonio Raffele with palette, brooding in front of his unfinished landscape; the jumbled sheets of the unmade bed next to him are a virtuoso of creamy, shadowy whites.

In An Out-of-Doors Study, c.1889, Madame Helleu is patently bored and fed up as she listlessly semi-naps next to her husband Paul, who is totally absorbed as he sketches by the river in the Worcestershire countryside. An Artist in His Studio,1904 (pictured above), shows us the bearded Antonio Raffele with palette, brooding in front of his unfinished landscape; the jumbled sheets of the unmade bed next to him are a virtuoso of creamy, shadowy whites.

What is so touchingly evident, in a way that contradicts the conventional view of Sargent, is the tender feeling, the personal empathy, that pervades almost all of the portraits here on view.

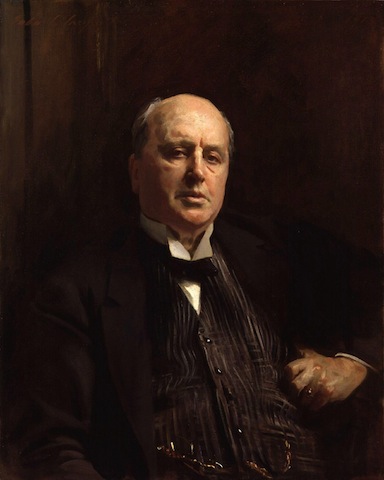

Perhaps not altogether surprisingly the most reticent, austere and reserved renderings are the self-portraits: he is enigmatic, impenetrable even to his own brush. Yet it is to Sargent that we owe, for example, definitive and memorable depictions of, say, Henry James, (portrait pictured left, painted in 1913), the fellow American who persuaded the artist to leave Paris to make his career in London. James is smug, formidable, but there is a curious hint of uncertainty, and an understanding perhaps of the kind of façade that James himself could so readily portray in words.

Perhaps not altogether surprisingly the most reticent, austere and reserved renderings are the self-portraits: he is enigmatic, impenetrable even to his own brush. Yet it is to Sargent that we owe, for example, definitive and memorable depictions of, say, Henry James, (portrait pictured left, painted in 1913), the fellow American who persuaded the artist to leave Paris to make his career in London. James is smug, formidable, but there is a curious hint of uncertainty, and an understanding perhaps of the kind of façade that James himself could so readily portray in words.

Although Sargent never married, or had, as far as is known, any sexual or emotional liaison (the gay world continually tries to co-opt him) he is served very well by his collateral descendants, among whom is Richard Ormond, the art historian who is the co-author of the outstanding, multi-volumed catalogue raisonée of Sargent’s oeuvre, and a curator along with those at the Metropolitan Museum where this show, in even more ample form, will travel.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Comments

I have been in love with