Rock 'n' Roll America, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

Rock 'n' Roll America, BBC Four

Rock 'n' Roll America, BBC Four

The story of popular music's ground zero had Little Richard and a big impact

One, two, three o’clock, four o’clock rock… For those who orchestrated the swing from blues to rock ‘n’ roll, it’s getting late. Like the Chelsea pensioners, their numbers are beginning to dwindle and, as time keeps on slipping, slipping, slipping into the future, their testimony must be recorded for posterity, lest it be lost for ever in the music mists (currently somewhere off the coast of Kintyre). Except – and it’s a fairly big "except" – this stuff’s already fairly well documented, no?

Well, maybe not. The job here was to convey the sense of newness and context in a way that would slap the modern viewer out of their complacency and leave them reeling in a real-life pull-focus as cognitive dissonance took hold and they processed the events, bypassing the solipsistic filter of their own life’s experience. It’s a tough ask by anyone’s standards, particularly for territory that people feel so familiar with. Gravitas, good footage and some on-form talking heads are the absolute minimum requirement.

This is a series about the origins not just of rock ‘n’ roll but of modern dance music

The gravitas box was ticked by a growling David Morrissey voice over, full of drama and flying low over the landscape. We started with the building of suburban America and the teenage rebellion that this newfound prosperity both fostered and enabled. Among this background to the story, we got a surprisingly astute focus on film. As well as providing a great story about how the B-side obscurity “Rock Around the Clock” stepped out of the shadows and on to the red carpet (by way of Blackboard Jungle star Glen Ford’s son, Peter, and his precocious record collection), this allowed us to see how youth rebellion was sold. Brando’s famous retort when asked what he’s rebelling against in The Wild One seems to sum it up, but perhaps not in the way one might expect. White American youth had pretty much bugger all to be angry about: many had cars, money and independence, but they were consumers now. It was very easy to make pointless, petulant immaturity and self-regard look cool, and it paid dividends.

Meanwhile, with segregation ensuring that black America could enjoy few of the benefits of modern living, it got on with the business of creating the soundtrack – and that’s what’s really important here, the meat in the gravy, so to speak. Which brings us rather neatly to the probable architect of it all – Fats Domino. The footage of him was a joy to watch, and as we focused on his hard, hammered triplets that forged such a distinctive sound, I couldn’t help but think he must have had his foot down hard on the sustain pedal, as its effect – and the dismissive sneers it elicited – still resonate today. The subsequent focus on the migration up the Mississippi corridor to Chicago and Detroit was equally captivating, taking in Sam Phillips’ Sun Studios on the way. Here, the industry’s search for a "white singer with a black voice" was to reach an end with the shaking hips of Elvis Presley, who proved a suitable stand-in until Paul Young claimed his rightful crown somewhere around 1983.

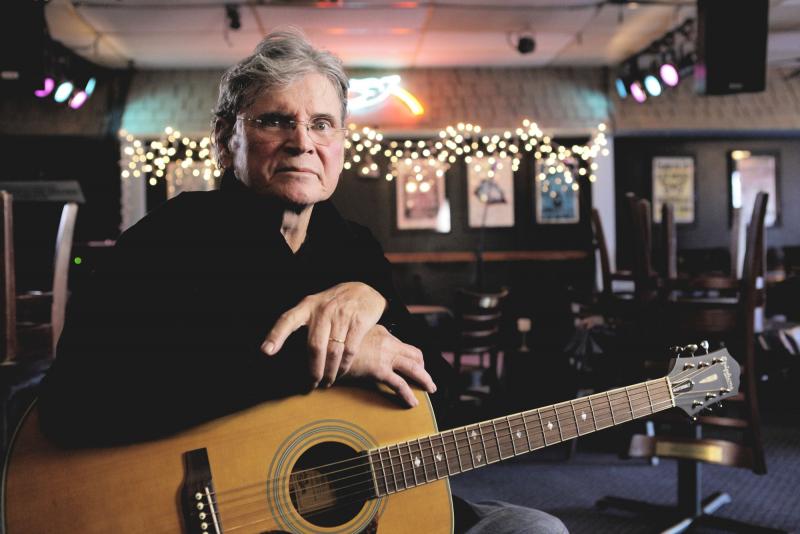

Seeing Little Richard give the rock ’n’ roll train a locomotive engine and some driving ambition was a delight, particularly when the realisation hit that the euphemistic origins of “Tutti Frutti” predated “I Wanna Hold Your Hand” by six years and made the Fab Four look about as dangerous and sharp as a chocolate knife in a heat wave. It was clear at this point, that this is a series about the origins not just of rock ‘n’ roll but of modern dance music. Dirty, filthy, sexy dance music. Allen Toussaint, Wanda Jackson, Don Everly and Jerry Lee Lewis… it was quite a roll call, and they all seemed to be in agreement: “Things were going on, man,” said Everly, looking deep into his mind’s eye. It seemed a good place to be.

There were occasional winces. I like Chuck Berry as much as the next person (unless that next person happens to be one of his waitresses, in which case there will be some discrepancy), but to compare him to Shakespeare is a bit rum. A masterful guitar player and performer, certainly. A great songwriter, for sure. A decent lyricist, yes. But Tom Jones’s insistence that Berry’s ability to come up with a different word for every beat puts him in the same category as the Bard is ridiculous (and also ignores the choruses). I mean, by that measure, the ultimate literary touchstone would be Dr fucking Seuss. Actually, that may be a fair point…

Minor nitpicking aside, there’s a reason why this was among the more successful of the BBC4 music documentaries, and it’s that it was given space to breathe and time to take – it’s the first of three parts. The luxury to rock on, and on, and on, is one that those funding such projects would be well advised to afford other genres.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Slow Horses, Series 5, Apple TV+ review - terror, trauma and impeccable comic timing

Jackson Lamb's band of MI5 misfits continues to fascinate and amuse

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Coldwater, ITV1 review - horror and black comedy in the Highlands

Superb cast lights up David Ireland's cunning thriller

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

Add comment