Man With a Movie Camera | reviews, news & interviews

Man With a Movie Camera

Man With a Movie Camera

Dziga Vertov's dazzling 1929 opus captures a day in the life of an idealised Soviet city

Dziga Vertov’s narrativeless “city symphony” Man With a Movie Camera celebrates the modernity and energy of the post-Bolshevik Revolution metropolis – a composite of Kharkov, Kiev, Moscow and Odessa filmed over three years. Propaganda for the harnessing of machinery in the building of the Soviet Union’s future, it was much more besides – a masterpiece of avant-garde experimentalism and, fleetingly, an unexpected critique of the continuing class struggle.

Inspired by Constructivism’s creed of art with a social purpose and its photo-montage techniques, Vertov’s poetic documentary was partially intended to repudiate subjective films derived from literature and theatre and derided by him as bourgeois fairytales. In a sense, it was Constructivism put to the service of deconstruction – fragmentation – and reconstruction. The day-in-the-life portrait of the idealised city comprises rapidly montaged images (often humorously or pointedly twinned) of myriad aspects of labour, industry and transport; leisure, domesticity, and the passage of life (marriage, birth, divorce, death), which, as the cutting accelerates at the climax, swirl in kaleidoscopic abstraction. They leave an overall impression of prosperity of body and soul under Communism: most of the Russians and Ukrainians observed seem happy or content with their lot.

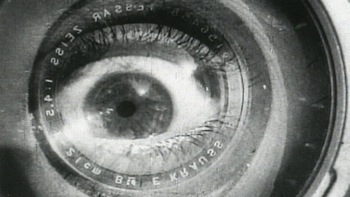

More than any of the other great early Soviet auteurs, Vertov, the leader of the Kinoks (from “Kino-oki”, or Cinema Eyes) group, which included his editor wife Elisaveta Svilova and his cameraman brother Mikhail Kaufman, championed the primacy of the camera (“kino-glaz”, or film-eye, pictured above) over the human eye in seeing truth and disseminating it.

More than any of the other great early Soviet auteurs, Vertov, the leader of the Kinoks (from “Kino-oki”, or Cinema Eyes) group, which included his editor wife Elisaveta Svilova and his cameraman brother Mikhail Kaufman, championed the primacy of the camera (“kino-glaz”, or film-eye, pictured above) over the human eye in seeing truth and disseminating it.

"I am kino-eye, I am a mechanical eye, I, a machine, show you the world as only I can see it," he wrote in a 1923 manifesto, a year after beginning the series of Kino-Pravda (“film truth”) newsreels on which he began the technical experiments that reached critical mass on Man With a Movie Camera, an almost delirious compendium of speeded-up and slow-motion shots, superimpositions, split-screen effects, surreally geometric juxtapositions within a single frame, primitive stop-motion animation, canted angles, and footage played backwards. Self-reflexive to the max, the meta-doc embellished by these tricks is shown being “simultaneously” photographed by Kaufman, cut together by Svilova in her editing suite, and projected to an appreciative audience in a cinema. (Pictured below: urban cotton worker.)

The idea of a mechanised eye was more of a conceit – one with a hint of directorial egocentricity – than a reality, since a cinematographer must obviously look into a viewfinder to control what is being filmed and use it to change perceptions, which was Vertov’s goal. Accordingly, the dominant motif in Man With a Movie Camera is a human eye behind a camera lens. It was probably Kaufman’s. He not only shot the film, but played the eponymous cameraman who was photographed risking life and limb to get the shots that Vertov wanted. Camera and tripod in hands, like Buster Keaton in The Cameraman (1928), he lies under a railway track to film the train that thunders over him (pulling a foot out of harm’s way in the nick of time), nonchalantly climbs a girder of an iron bridge and a factory chimney, hangs from another train, and stands, Keaton-esque, between trams that pass on either side of him. (The brothers unsurprisingly never worked again.)

The idea of a mechanised eye was more of a conceit – one with a hint of directorial egocentricity – than a reality, since a cinematographer must obviously look into a viewfinder to control what is being filmed and use it to change perceptions, which was Vertov’s goal. Accordingly, the dominant motif in Man With a Movie Camera is a human eye behind a camera lens. It was probably Kaufman’s. He not only shot the film, but played the eponymous cameraman who was photographed risking life and limb to get the shots that Vertov wanted. Camera and tripod in hands, like Buster Keaton in The Cameraman (1928), he lies under a railway track to film the train that thunders over him (pulling a foot out of harm’s way in the nick of time), nonchalantly climbs a girder of an iron bridge and a factory chimney, hangs from another train, and stands, Keaton-esque, between trams that pass on either side of him. (The brothers unsurprisingly never worked again.)

These stunts were integrated into Vertov’s politically charged depiction of the fusion of man and machine on the street and in the workplace. The wittiest such images show women at the mercy of slimming machines. Vertov (pictured below) seemingly wasn’t a dour artist-apparatchik chronicling Party achievements; he, or at least Svilova, included many sensual images, especially of attractive women – among them a sleepyhead slipping on her bra, a Louise Brooks lookalike, a sports spectator unnecessarily wearing a spotted veil – or their legs. Or were the gifted editor and her husband sugaring the pill? If so, they pay, to their credit, special attention to the face of a wizened old woman of peasant stock at a market, a babushka who would have remembered the emancipation of the serfs back n 1861.

The shot Kaufman most relentlessly pursues is of two well-dressed women sitting with family members in a horse-drawn carriage as a camera car runs alongside it; one of them coyly imitates Kaufman cranking his camera. It makes a stark comparison to his shots of the waking vagrants, including a woman who turns quickly away from him, at the start of the film. Vertov doubtless didn’t endear himself to the authorities by showing that some Soviets were still richer than others. The shock registered in the wide-open human Kino-eye staring at the viewer from its lens may have been his way of expressing horror at the persistence of inequality.

The shot Kaufman most relentlessly pursues is of two well-dressed women sitting with family members in a horse-drawn carriage as a camera car runs alongside it; one of them coyly imitates Kaufman cranking his camera. It makes a stark comparison to his shots of the waking vagrants, including a woman who turns quickly away from him, at the start of the film. Vertov doubtless didn’t endear himself to the authorities by showing that some Soviets were still richer than others. The shock registered in the wide-open human Kino-eye staring at the viewer from its lens may have been his way of expressing horror at the persistence of inequality.

The newly restored Man With a Movie Camera is accompanied by a soundtrack by Alloy Orchestra. The Blu-ray version released simultaneously features Michael Nyman’s score and an impressive array of extras, including Vertov’s Kino-Pravda No 21 (1925), One Sixth of the Globe (1926), and Three Songs of Lenin (1935).

- Man With a Movie Camera opens July 31 at the BFI, and on limited release around the UK and Ireland

Overleaf: watch the BFI restoration trailer for Man With a Movie Camera

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

Don't Let's Go to the Dogs Tonight review - vivid adaptation of a memoir about a Rhodesian childhood

Embeth Davidtz delivers an impressive directing debut and an exceptional child star

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

One Battle After Another review - Paul Thomas Anderson satirises America's culture wars

Leonardo DiCaprio, Teyana Taylor, and Sean Penn star in a rollercoasting political thriller

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Comments

Very interesting article on