Don Juan, Lesya Ukrainka Theatre, St James Theatre | reviews, news & interviews

Don Juan, Lesya Ukrainka Theatre, St James Theatre

Don Juan, Lesya Ukrainka Theatre, St James Theatre

Actors excel in Ukrainian classic despite symbolic overload

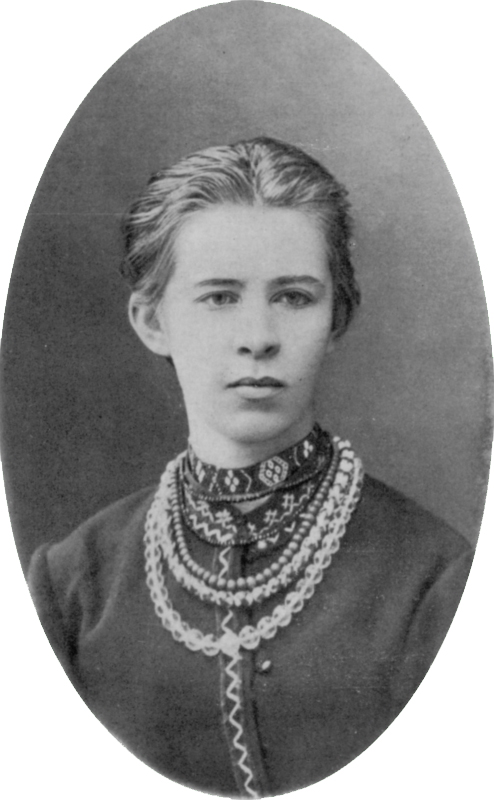

Whose Don Juan – progenitor Tirso de Molina’s, Molière’s or Pushkin’s? None of the above. Unless you have some knowledge of Ukrainian culture, you won’t have heard of Lesya Ukrainka, born Larysa Petrivna Kosach-Kvitka in 1871 to a proudly nationalist (if half-Byelorusian) father and a mother whose pioneering work in women’s rights she continued.

Her Don Juan of 1912, written a year before her untimely death from tuberculosis, was the seminal play which director Konstantin Khoklov staged in 1938 to bring true Ukrainian drama to the leading Kiev theatre. Its name changed as a result, from Kiev State Russian Drama Theatre to the Lesya Ukrainka National Academic Theatre of Russian Drama (to give its full title). This is the company which has been performing two plays about, not exactly by, Chekhov and a Turgenev adaptation on anything but a shoestring at the St James Theatre, and though I wish I’d caught those too, I’m proud and happy to have seen their final offering.

This is deep and serious work by a fine ensemble of actors, and the take of Ukrainka (pictured right) on a legendary figure is essential viewing. True to her feminist credentials, she makes Don(n)a Anna the powerful figure, the woman who wants both the power of her status as the wife of the Commander (read Commendatore if you prefer to think in Mozartian terms) – not his daughter, note, since this version follows the Pushkin line – and the passion of the outsider-lover, whose lack of what veteran director Mikhail Reznikovich calls integrated personality renders him ultimately the weaker figure. Since she wavers between the two for much of the play, the fatal killing which happens minutes in to Mozart’s opera occurs here near the end of the play, running, like the company’s other shows, without an interval, at one hour 40 minutes.

This is deep and serious work by a fine ensemble of actors, and the take of Ukrainka (pictured right) on a legendary figure is essential viewing. True to her feminist credentials, she makes Don(n)a Anna the powerful figure, the woman who wants both the power of her status as the wife of the Commander (read Commendatore if you prefer to think in Mozartian terms) – not his daughter, note, since this version follows the Pushkin line – and the passion of the outsider-lover, whose lack of what veteran director Mikhail Reznikovich calls integrated personality renders him ultimately the weaker figure. Since she wavers between the two for much of the play, the fatal killing which happens minutes in to Mozart’s opera occurs here near the end of the play, running, like the company’s other shows, without an interval, at one hour 40 minutes.

Headlong drama it isn’t. The style sits somewhere between those of two far more swankily backed and blingily attended recent Russian visitors – much more involving than the incomprehensible mannerisms of three Vakhtangov Theatre productions, not as fluent as the Chekhov of Andrey Konchalovsky’s Mossovet State Academic Theatre (though comparisons with realism aren't exactly fair). On an elaborate set designed by Maria Lewitskaya which starts out looking a bit like a tacky Witch’s Den in somewhere like Tintagel or Glastonbury but opens up to enticing Velazquezian perspectives, the actors are constantly hedged in by an often obscure symbolism which threatens to smother what they’re so eloquently saying, chucking giant chess pieces about or being upstaged by a mute girl in white who mimes playing the violin (to the most frenetic sequence of Schnittke’s frenetic Concerto Grosso No. 1). At least all of this is disciplined, never aimlessly cluttering up the stage. As with the Vakhtangov company, the soundscape music is almost constant, sometimes distracting from eloquent speech, but when the actors need to move or dance to it, they do so with unflinching physical accomplishment.

Much remains obscure, above all why the principals have to repeat their idées fixes on a telephone in front of the water-channel which frames the main stage, and I’m still at a loss to know exactly what happens at the end – clearly the Commander as Stone Guest returns, but does Anna die as well as Juan (who doesn’t go to hell)? But there’s great intensity from the nervy Anna of Natalya Dolya, Eugeny Avdeenko’s very masculine, charismatic Juan and Olga Kulchitskaya's superseded. Dolores. Like the main pair of lovers, Vladimir Raschyk’s Commander (pictured above with Dolya) is both powerful and young – a crucial point when in contrast to their contemporary dress the guests at his party are ossified figures from the court of Velazquez’s Philip II, executing several dances of death across the front of the stage and constantly underpinning the action in routines well choreographed by Alla Rubina. Reznikovich, now 77 and perhaps the leading force in Ukrainian theatre, is making his clearest point here about the tension between conventions of honour and status on the one hand and impulsive youth on the other.

Much remains obscure, above all why the principals have to repeat their idées fixes on a telephone in front of the water-channel which frames the main stage, and I’m still at a loss to know exactly what happens at the end – clearly the Commander as Stone Guest returns, but does Anna die as well as Juan (who doesn’t go to hell)? But there’s great intensity from the nervy Anna of Natalya Dolya, Eugeny Avdeenko’s very masculine, charismatic Juan and Olga Kulchitskaya's superseded. Dolores. Like the main pair of lovers, Vladimir Raschyk’s Commander (pictured above with Dolya) is both powerful and young – a crucial point when in contrast to their contemporary dress the guests at his party are ossified figures from the court of Velazquez’s Philip II, executing several dances of death across the front of the stage and constantly underpinning the action in routines well choreographed by Alla Rubina. Reznikovich, now 77 and perhaps the leading force in Ukrainian theatre, is making his clearest point here about the tension between conventions of honour and status on the one hand and impulsive youth on the other.

I’d like to have heard the often beautiful delivery of the text without the admirable English narratives in my earpiece, but better that than the inadequate intermittent précis we got in the Globe to Globe Festival: if supertitles are too expensive, this is a good second best and took me back to the days of National Film Theatre 3 when in order to keep the screen pure of subtitles, you got those voices in the ear. I apologise for proselytizing about this wonderful ensemble – 24 actors, all consummate in movement – towards the end of the company's run in the intimate surroundings of the St James Theatre, with a full house mostly consisting of attentive young Ukrainians, but let’s encourage them to return. The more we know about Ukrainian culture, the more we’re likely to root for this troubled but courageous fledgling democracy. A visit to Kiev beckons.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

50 First Dates: The Musical, The Other Palace review - romcom turned musical

Date movie about repeating dates inspires date musical

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

Bacchae, National Theatre review - cheeky, uneven version of Euripides' tragedy

Indhu Rubasingham's tenure gets off to a bold, comic start

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Harder They Come, Stratford East review - still packs a punch, half a century on

Natey Jones and Madeline Charlemagne lead a perfectly realised adaptation of the seminal movie

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

The Weir, Harold Pinter Theatre review - evasive fantasy, bleak truth and possible community

Three outstanding performances in Conor McPherson’s atmospheric five-hander

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Dracula, Lyric Hammersmith review - hit-and-miss recasting of the familiar story as feminist diatribe

Morgan Lloyd Malcolm's version puts Mina Harkness centre-stage

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

Reunion, Kiln Theatre review - a stormy night in every sense

Beautifully acted, but desperately grim drama

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Code, Southwark Playhouse Elephant review - superbly cast, resonant play about the price of fame in Hollywood

Tracie Bennett is outstanding as a ribald, riotous Tallulah Bankhead

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

The Lady from the Sea, Bridge Theatre review - flashes of brilliance

Simon Stone refashions Ibsen in his own high-octane image

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Romans: A Novel, Almeida Theatre review - a uniquely extraordinary work

Alice Birch’s wildly epic family drama is both mind-blowing and exasperating

Add comment