theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Mark Wigglesworth | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Mark Wigglesworth

theartsdesk Q&A: Conductor Mark Wigglesworth

English National Opera's new Music Director on Shostakovich, silence and 'accessibility'

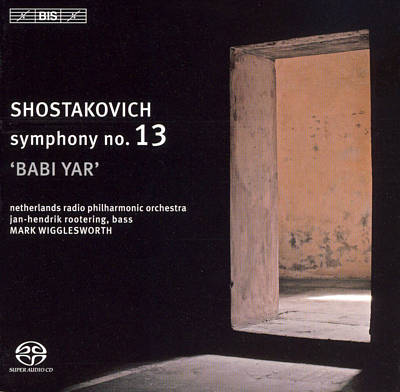

Mark Wigglesworth and I go back quite a long way in terms of meetings – namely to 1996, when I interviewed him for Gramophone about the launch of his Shostakovich symphonies cycle on BIS. He completed it a decade later, though that release hung fire until last year.

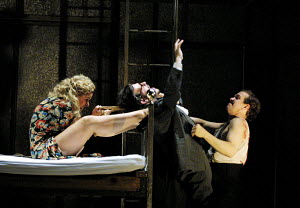

Now, then, is just the right time. Having literally stunned us with his deep, dark conducting of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk at ENO in 2001, Wiggesworth is back with the same opera to mark his inauguration as the company’s Music Director – just about the only candidate who I guarantee won’t disappoint after the amazing success of Edward Gardner’s tenure (Wigglesworth was also one of the options at the time that Gardner took the job). His track record with ENO is one of pure success: the most meaningful Cosi fan tutte I’ve ever seen on stage, in Matthew Warchus’s production with Susan Gritton, Mary Plazas, Janis Kelly (pictured below) and Toby Spence in the cast (though a Barbican staging wasn’t as successful) – followed by a Parsifal which converted theartsdesk’s vehemently anti-Wagnerian Igor Toronyi-Lalic, and a total fusion of drama and music in Janáček'’s Katya Kabanova so powerful I went twice.

To prepare, I made sure I listened to each one of the symphonies recordings I’d not caught up on, and found all of them held their truthfully recorded and incisively interpreted ground alongside the most successful of the recent cycles, Vasily Petrenko’s with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (Wigglesworth's own notes to each instalment are full of startling new insights). So that’s where we started, before moving on to the opera and ending up with issues of “accessibility” and selling tickets at ENO, challenges facing the company as it moves, reeling from the blow of the Arts Council’s capricious cut but artistically never in better shape, into its new era.

To prepare, I made sure I listened to each one of the symphonies recordings I’d not caught up on, and found all of them held their truthfully recorded and incisively interpreted ground alongside the most successful of the recent cycles, Vasily Petrenko’s with the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra (Wigglesworth's own notes to each instalment are full of startling new insights). So that’s where we started, before moving on to the opera and ending up with issues of “accessibility” and selling tickets at ENO, challenges facing the company as it moves, reeling from the blow of the Arts Council’s capricious cut but artistically never in better shape, into its new era.

DAVID NICE: You started your cycle of Shostakovich symphonies when we first met, with the Seventh ["Leningrad"], in 1996 and the final release, of the First and Fifteenth, appeared last year. Do you wish you could go back and do anything differently?

MARK WIGGLESWORTH: When I first did them, the confidence you feel you need to create a performance comes from a conviction that this is how it has to be, and I’ve done some of these pieces 50, 60 times. And that’s performing, not counting the rehearsals. When you do them over and over again with different orchestras, different oboists and even different leaders of the orchestra, you realize that it’s fine – not to be completely different, but another way works too. And you’re still being true to your vision of what this music is saying.

Your mind is flexible enough to embrace the change.

That’s right, it’s like a satnav which has a goal that it’s heading to, and you decide to take a slightly different route, and it recalculates and either says, that’s fine, if you want to go this way we will, or else it says turn round where possible. And if you know when to trust and when to lead, that’s the secret. You never get it really right, but that philosophical conflict is quite clear to me, that it’s when to let go and when to demand both musically and psychologically.

It’s interesting that finally very recently listening to them all together…

Did you notice a big difference [between the recordings with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales – Wigglesworth pictured left by Ross Cohen at the start – and the later ones with the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra]?

Did you notice a big difference [between the recordings with the BBC National Orchestra of Wales – Wigglesworth pictured left by Ross Cohen at the start – and the later ones with the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra]?

I didn’t, no, that’s what surprised me, I’ve said to you before that what amazed me is this depth of sound that you always get anyway, but between the Wales and the Netherlands performances – they’re both orchestras that one doesn’t think of, perhaps unfairly, as in the front league, and yet they sound it, and bears out why I think that it’s daft to put up a list of the world’s best orchestras, it should be about the world’s best partnerships. [MW laughs]. But they sound remarkably similar to me, I don’t know what you think.

Well, to be honest, I haven’t listened, of course I listen to the edits and I’m very much part of the process, but I don’t think I’ve listened to any of them since they’ve been released, and that’s why I’m curious to know, not specifically about the Welsh being different from the Dutch, but me being different; and the Shostakovich symphonies, though they are so different as individual pieces, there’s always a unified voice coming through them, and I’d be curious to know whether that voice had changed.

What seemed incredibly consistent was the sense of space, without being slow, the articulation, which is so clear and all dynamics working, and also of course, this is partly the BIS recording, but when it’s ppp it’s some of the quietest sound I’ve heard on CD.

And people accused us of manipulating, we haven’t. It’s interesting what the whole CD listening experience: is it, as I’m sure you do, sitting down and listening, getting a volume that can cope and making an active decision to listen, or is it chucked in the car when you’re driving around the M25, in which case you’re going to have a problem? BIS’s philosophy, which I’m proud to be part of, is that we make records for people who really want to sit down and listen to them, and that’s maybe taxing for your neighbours on the one hand and your ears on the other. They don’t compress and we work really hard to play as quietly as we can.

They used to have caveat on the front about the dynamic range. I’ve just heard, and was moved to tears by the dynamic range of the Netherlands Radio Choir on the Thirteenth ["Babi Yar"] Symphony – also their Russian seemed so clear. And their crescendos and decrescendos are so impressive.

I think the Thirteenth and the Fourteenth are the two for me that I never want to stop doing, and I think it’s the texts that give you the confidence of what the music’s actually about, because although you have a sense of what the others are about, you can’t argue with the texts.

I think the Thirteenth and the Fourteenth are the two for me that I never want to stop doing, and I think it’s the texts that give you the confidence of what the music’s actually about, because although you have a sense of what the others are about, you can’t argue with the texts.

It always amazes me that Prokofiev never lived to that time when he could say exactly what he meant, but Shostakovich did, with Yevtushenko’s poetry – it’s very specific and clear and almost hard, and that “Fears“ movement, there you have the document of what was felt in the 1930s and 40s.

Terrifying, absolutely terrifying.

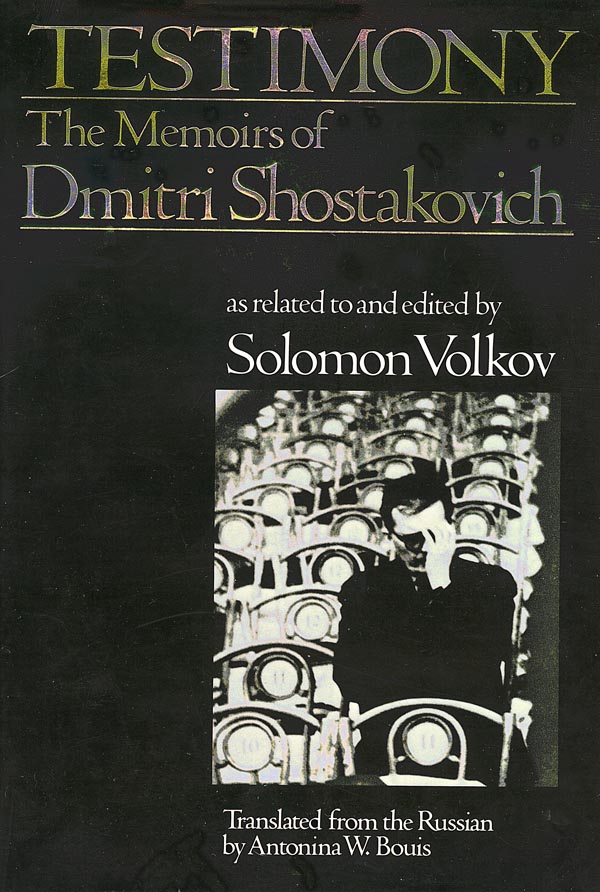

This interests me – when you started you were very Testimony-based [on the book which purports to be Shostakovich’s memoirs “as related to and edited by" Solomon Volkov]: we know that there’s been controversy since then about how authentic it is. I think that fundamentally there’s great truth in there, only doubt about by which route it came, but it’s still a useful guide.

I think it’s a bit of a red herring, Testimony, in that people talk about the legality about it. I mean, OK, but as far as I’m concerned if Ashkenazy, Rostropovich, Kurt Sanderling, Victor Liebermann believe the essence of it, then that’s good enough for me. It’s not a question of whether literally he’s writing. The point that matters is, is this what the music is expressing? And if you listen to the music, it is. I remember reading it for the first time and devouring it. And in my notes I’ve always tried to be semantically careful, trying to not create an obstacle to the view. It seems to me in the music, and I would like to think that I didn’t need to read Testimony to hear that.

Sure, it just confirmed what you felt.

And I like to think that people can hear the music without any knowledge of it, and what’s interesting about Shostakovich’s life as a composer, he’s probably the only composer whose context does add to your experience. But I would still like to think that he is a great enough composer that that experience can speak to people subliminally. And I agree that it can be taken too far when it’s said, "Oh if it’s a two-note figure which represents…" But when I do the Tenth Symphony, you’re not thinking Stalin, you’re thinking evil and brutality and anger, and you’d think that whether it was Stalin or not. But as an historical document, these symphonies are equally fascinating.

They’ve often been described as a developing chronicle of Soviet history…

Although what’s depressing, and equally fascinating, is that if you listened to the 15 symphonies not knowing their numbers, what order would you put them in? And I don’t think you would put them in the order in which they were written. I did that as an experiment. You’d put One first, do you know what I mean? Is Six a development...

And Four could belong to when it was actually first performed, in the 1960s, 30 years after it had been composed...

Exactly. And you’d probably put 11 and 12 probably earlier than 8; 9 you’d certainly put earlier. So a logical development emotionally doesn’t work, and I think why I find it depressing is that the Soviet Union was just repetition, the ability of history to repeat itself across decades, centuries..

And you look at “A Career” in the Thirteenth Symphony, and I think of a certain Russian conductor operating today, someone who’s signed the Faustian pact with Putin to keep and build on what he has, and this is a great interpreter of Shostakovich.

And you look at “A Career” in the Thirteenth Symphony, and I think of a certain Russian conductor operating today, someone who’s signed the Faustian pact with Putin to keep and build on what he has, and this is a great interpreter of Shostakovich.

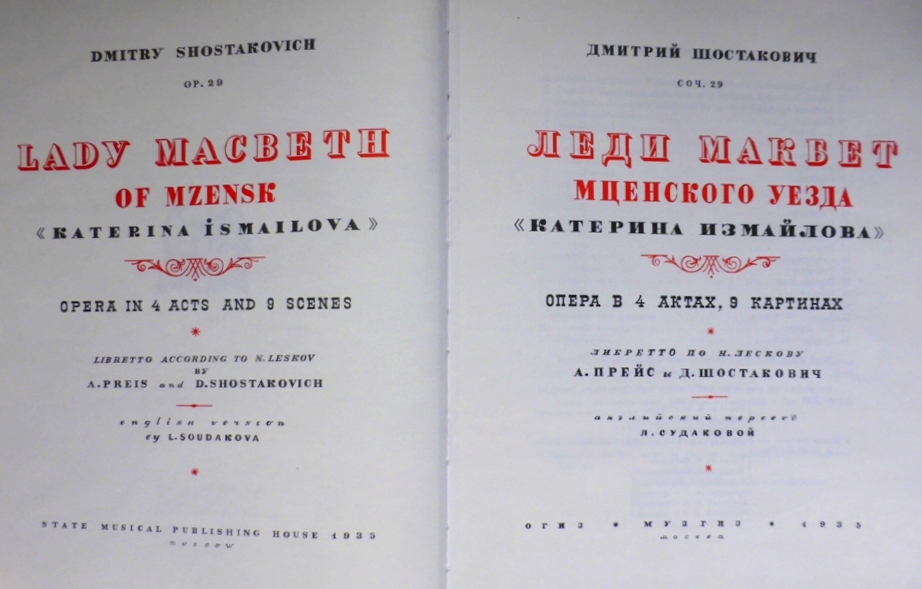

Well, I’ve written an article for The Independent which will probably come out before your interview, full disclosure, I don’t want you to think that you’re duplicating, but – they said, would you just write something about Shostakovich, and I didn’t know where it was going to take me, actually; I didn’t want to write the obvious about the Pravda article denouncing Lady Macbeth [in 1936, nearly two years after it had opened, as “chaos instead of music”, which marked the crackdown on freedom of expression in the arts], it’s fascinating and it needs to be said…

That’s the one thing everyone knows about Shostakovich.

Exactly. And when I started thinking about the feminist angle of this piece, and Shostakovich’s desire to write a kind of Ring for women, a tetralogy about Russian women, I’d forgotten about that…

I always wondered about it, whether he said that just for the public record...

Where I am at the moment, I think it’s massive, and this piece as a feminist tract – the relevance of it today is extraordinary and terrifying, and I started doing some research on feminism in Russia – it was unbelievable.

You mean now?

Now, and since Stalin. And the extraordinary thing is that immediately after the Revolution, it was an optimistic time for women. It was when Stalin arrived that this need for machismo style of politics increased, and now we have the sexualisation of Putin now – and when you’re talking about now, look at Pussy Riot – their crime was feminism. To discover the relevance of this piece today was both good and bad. So I think – there are the women “In the Store” in the Thirteenth Symphony. I don’t think he was a feminist in the political sense…

…and his wives were there to look after him.

But I think he saw himself as the voice for any oppressed individual or group, whether it was Jews or women or the Hungarians in 1956, whoever the oppressed people of the time were. And I think women are a part of that group of people for him. I certainly didn’t think that before.

Next page: on Shostakovich's Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and Tcherniakov's production

Does anything that [the director of the ENO production of Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk Dmitri] Tcherniakov’s done affect that? Because I didn’t see this production when it was done in Germany, the images are wonderful…

As you know the Pountney production was iconic and I’m relieved and thrilled to say that this could not be more different in a way that I believe is equally valid. Shostakovich said the piece was a tragedy-satire, and Dostoyevsky said that tragedy and satire were the twin sisters of truth, so maybe I’m being a bit simplistic, but Pountney’s production was very strong on the satire. And it was brilliant, I loved it, while this is on the tragedy, and there is not a single gesture in it that doesn’t come from the music (pictured above: Patricia Racette as Katerina in the ENO production, photo by Clive Barda). That’s unusual. He does hear it in a way that’s incredibly sincere, he knows these women – and the men.

Has he been here working on it?

Every day. It feels brand new, to be honest. The Dusseldorf production was a long time ago and obviously the set arrives and it is what it is and you work with that set, which is not without its challenges in a different auditorium, but in the work with the singers we’ve all felt it’s a new production. That’s as it should be.

I didn’t realize that Patricia Racette was singing Katerina until recently, and of course you did Janáček'’s Katya Kabanova with her, pictured right, which contains a similar situation – the downtrodden daughter-in-law has to make obeisance to her husband’s powerful parent.

I didn’t realize that Patricia Racette was singing Katerina until recently, and of course you did Janáček'’s Katya Kabanova with her, pictured right, which contains a similar situation – the downtrodden daughter-in-law has to make obeisance to her husband’s powerful parent.

It’s very similar, the Leskov story [The Lady Macbeth of the Mtsensk District] is intriguing to read because there is no moral judgment.

And her most appalling crime in it, the murder of a nephew, is cut out of the opera.

Exactly, well, it always helps to make people more sympathetic if you get rid of the child murder. I think it’s interesting that in order to make her sympathetic, Shostakovich thought, I can’t write music that will defend a child-murderer, I can write music that can defend all the other murders, and he does. But when you read Leskov there is no emotional value put to her action, so your judgment towards her is different, in that you’re not manipulated. Shostakovich is very manipulative, he makes it incredibly difficult for you not to feel sorry for her, not only by making all the men real shits, extremely so, but he gives her these tunes, this music, and the power of music to overcome your moral compass: I mean if you do feel sorry for her, really? You’re not condoning murder, but when you hear those harmonies and the gut-wrenching loneliness of her solos, you have to be on her side, and I think that’s the power of music that Stalin was terrified of. It’s not so the satire and the sex scenes or the send-up of the chief of police, it’s not the difficulty of the music, because it’s popular and incredibly accessible, it’s not modernist in the Wozzeck sense…

Or even The Nose [Shostakovich’s first full-length opera of 1929].

Exactly. So what Stalin feared – we know he was a musician in that bizarre way that Hitler was as well – it’s such a strange thing for us all to deal with, that monsters can be touched by music, but I think Stalin saw the power of that and he was terrified.

We’ll never know how he responded emotionally, will we? Because the stereotype is to think that all the bureaucrats were idiots and they didn’t hear between the lines, but many of them did.

We’ll never know how he responded emotionally, will we? Because the stereotype is to think that all the bureaucrats were idiots and they didn’t hear between the lines, but many of them did.

I think he did, and that begs the question: Why did Shostakovich survive? Hardly any of his friends did. Why did Stalin spare him – really, was he that famous? He wouldn’t have been that famous if he’d dealt with him in 1936. So it is a fascinating thing – and Testimony talks about Stalin dying to a Mozart piano concerto going round and round, and the story of the recording of that concerto was Stalin hearing a lady playing on the radio and saying, I want that record, and the staff realising it was a concert, and overnight they made a single pressing, they rang her up – so this is all Testimony, so who knows? As I say, I think you can get bogged down in it, but I think that Stalin’s understanding of music was probably valid.

We know much less about that than Hitler’s very precise views on Wagner and Bruckner…

Much to those composers’ loss, of course.

In the same way that people bang on about Wagner and Hitler, they bang on about the Lady Macbeth scandal. What I find interesting about that Pravda article is that it’s actually quite correct, about screaming and neurosis.

Yes, and there were plenty of American critics who said the same thing.

“Pornophony”.

Right.

Can you remember details about the 2001 Lady Macbeth at ENO? I remember Vivien Tierney very vividly [pictured right], and one moment crystallized it all for me, that moment on the death of the father-in-law when the brass band on stage just blasted out and I nearly fell off my seat. What’s changed in the way you hear the music now?

Can you remember details about the 2001 Lady Macbeth at ENO? I remember Vivien Tierney very vividly [pictured right], and one moment crystallized it all for me, that moment on the death of the father-in-law when the brass band on stage just blasted out and I nearly fell off my seat. What’s changed in the way you hear the music now?

I think it’s related to what we were saying at the beginning. The brass band are not on stage in this, they’re in the boxes, so they’re powerful, but there’s a disconnect between what you see and what you hear in this production as opposed to the Pountney one. What’s interesting about this production is it’s so intimate. It’s very much close-up.

That’s difficult to achieve in the Coliseum, but not impossible.

Yes. But when you’re looking at this one face and you hear that music, not specifically that moment, it changes how you do it. Because it is in her head, and the audience aren’t really watching much, and so it’s a subconscious thing that I hadn’t really thought about until you asked. But I would like to think that it is equally powerful. Right now I think it’s more powerful, but we’re not in a sort of competition. It’s terrifying to think of that power, 15 brass players in addition to the ones in the pit, in your head, you think, goodness, Shostakovich heard that in his head.

That’s not a fashionable view, the internalizing. I remember when the Borodin Quartet played the 15 quartets in Norwich, I was challenged when I placed Britten on the level of Shostakovich for the inner tensions, and someone in the audience challenged that. And I said, not only that, but the fact that Britten and Shostakovich had such similar angsts, yet they lived under different systems. Of course for Britten there was another sort of oppression...

Exactly. I think their connection was because they both felt trapped, they both felt imprisoned, and they are kindred spirits, unquestionably.

That later meeting when they picked up from each other I find very moving.

One of the things that struck me was that when I first did this opera I’d only done, probably, five of the symphonies, and now I’ve done them all, and coming back to Lady Macbeth what fascinates me is that he saw his whole life at the age of 24 – he knew what it was going to be like. And he wrote it before the Pravda attack. He was celebrated, he was incredibly popular and sparky. And yet you could imagine this piece being autobiographical, identity with the suffering individual, and the satire and the wit and the power, everything in the symphonies is in there. Of course in his later works he quoted from Lady Macbeth, so there is a false mirror effect going on, but it doesn’t feel like a young man’s piece. Occasionally on a musical level it does, but not on an emotional level. And what’s interesting about the musical thing is there are actually three versions – ’32, the ’35 score which is a piano score with some modifications, also pre-Pravda, and then the Katerina Izmailova of the 1960s. I’ve looked at all of those and I’m informed about all of them in my choices.

You’ve not conducted Katerina Izmailova as well?

No. But what’s interesting about the anti-Testimony people, and there’s an interesting article in The Shostakovich Companion by Rosamund Bartlett, and it’s quite supportive of Katerina, on the basis that Shostakovich said towards the end of his life, “This is the only version that should be played”. Now of course we, the Testimony-ites, would say, Well he would say that anyway. But what’s interesting for a musician is that although the later version cuts out the rawness of the drama and the violence, the corrections he made I believe have to be valid. And all the metronome marks are slightly different, and it’s not that all of it is a lot slower, a lot is a little bit slower, and I’ve tried to find the balance in the choices I’ve made, which are quite self-conscious changes, between maintaining that raw, unbelievable energy of a 24-year-old, all of that nerve-wracking stuff with a composer of the experience of another 35 years.

So you wouldn’t take on any of the new music?

So you wouldn’t take on any of the new music?

I haven’t changed notes or cut bars or anything, but the tempos and dynamics mean that you do realise what he wanted to hear. Hopefully we’ll keep that shock and awe, but in the article the gist is, Why do we assume he was lying when he said, this third version is the one I want to perform? It’s an interesting question; we shouldn’t be held spellbound by our own tyranny of Testimony, I think it’s best to keep an open mind: that’s what I’m trying to do at the moment. We’re also doing Force of Destiny at the moment as you know, those versions are only seven years apart and the differences between those are unbelievable and fascinating.

Which version are you going for?

Musically we’re doing the later version. Whether that’s what you see on stage is another matter, and I’ve talked to Calixto [Bieito] about it, and theatrically the first version feels true.

Where Don Alvaro hurls himself off the rock at the end?

Yes, Calixto’s view is: Well, maybe he doesn’t have to do that, but really, is he going to walk off into the sunset? But just as a musician – we’re changing the third act order, because we know Verdi was never happy with it. But how he changed in seven years – there’s not a single bar that’s not more interesting in the later version. So it’s interesting that Shostakovich didn’t change that much, and that’s what I meant about the symphonies – you could listen to the Fourth Symphony and it could be his last work.

Next page: on Stalin, silence and the ENO experience

It’s probably wrong to say he didn’t have the breadth, but when you listen to Britten, there’s a lot of joy in the earlier stuff, and with Shostakovich I don’t know that there’s ever joy as such.

But that’s the Russian soul, isn’t it? I told this story a lot not to newspapers but to friends, because I find it extraordinary – when I did the “Leningrad” Symphony in Los Angeles, one of the violinists said to me that she was born during the Siege, and we were sharing the unbelievable horror stories of what people did to each other, then she looked at me square in the eyes and said: “Of course, it’s much worse now.” And this sort of suffering soul of the Russians which goes on… this was in the Nineties. But now, 25 per cent of Russians would vote for Stalin, Putin is celebrating…

It’s almost more Stalinistic than Stalin in every way except the killing.

We have to hope except the killing. Five million people were in the gulags before they admitted they existed, so we have to hope that Google Earth gives us a bit of help…

We have to hope except the killing. Five million people were in the gulags before they admitted they existed, so we have to hope that Google Earth gives us a bit of help…

People are still being removed. Actually to me, reading what Mussolini was up to in the 1930s, it’s more like that, but there are Stalinist aspects.

If it hadn’t been for Shostakovich I wouldn’t have known anything about Stalin as a student. Because in the mid-Seventies at my school we had to write an essay on whether Stalin was a great man or not, and I remember my mother’s horror at me being asked to write this essay: what were the good points and what were the bad points? Her horror at what a 12-year-old boy was being asked to engage in.

This is your mother not with a particular background, but just knowing…

She knew. And I can’t remember how that particular history lesson ended, but in the 70s everyone was very proud of how they stood up to Hitler, and Stalin was slightly more complicated and embarrassing, so perhaps best not to talk about him that way in history lessons. In England we like to think we’re terribly truthful and honest and open, but that was my history lesson on Stalin. It was only through music – I remember studying the Tenth Symphony for A Level, and through that you get to the history, and then you begin to realize… And that’s why the music is so important. People say, why do you do so much Shostakovich? Essentially because I love the power it has to express both private and public emotions, it’s a real privilege to be part of that. But it’s so much more than that, and that’s why the historical context does matter.

I don’t think it’s just because of the historical context that Shostakovich symphonies now fill a hall, it’s because of how it speaks.

I reckon there are 11 of the 15 symphonies that would be in a concert programme and no-one would raise an eyebrow. Two and Three, 12 – apart from them the others are regularly performed. That’s more than any other symphonist ever – Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Mahler even. Why? As you say, it’s not just people coming for a history lesson. And the most popular classical music is popular for a reason, not because it’s populist but because it’s the greatest music, whether it’s Beethoven Five or Brahms Four, Meistersinger or La Boheme.

And it requires the greatest concentration.

We underestimate the public as performers at our peril.

Newspapers underestimate the public all the time. I don’t know why this is, but the idea that at just about every Prom I went to there were 5,500 people [Mark Wigglesworth at the 2014 Proms by Chris Christodoulou] – at some very mixed programmes…

Newspapers underestimate the public all the time. I don’t know why this is, but the idea that at just about every Prom I went to there were 5,500 people [Mark Wigglesworth at the 2014 Proms by Chris Christodoulou] – at some very mixed programmes…

We need to embrace that rather than give the impression that classical music is – the fact that classical music is a challenge is its greatest strength. Whether it’s cricket or religion or classical music, these major areas of our lives that are struggling to maintain their audience give up their essence at great risk, I think.

I was reading a piece today which maintained that “classical” concerts are a conflict zone between people who are uptight or laid back. It was saying, people need to loosen up. It was saying there’s a division and there needs to be a unity, but actually there’s a great unity in silence, the intensity of the way people listen. And you can’t lose that in a Mahler or Shostakovich symphony, where the silence is a crucial part of the performance. .

We’re all terrified of silence, aren’t we? And when I’ve done these Shostakovich pieces there are incredibly silent moments and there are audiences that can’t cope. They only get coughs at those moments because they can’t cope. They are hearing the silence, it’s there, and for many people it’s terriying. I used to think it was because they weren’t listening, and though I think that’s valid in certain cases, I think that for some people it’s frightening. And we fight that everywhere, in the idea that noise is better than silence, whether you’re in a hospital or a bookshop, it’s extraordinary. It’s extraordinary the idea that music needs to be louder to be better, to be more relaxing. We know that music raises your blood pressure. It cannot therefore be a relaxing motivator, and the Pipe Down campaign is absolutely vital, to maintain our right to the privacy of our mind.

If it could be seen as active meditation, though I know that’s a different thing, no-one would think of using their mobile phone during meditation.

No, although most places where you go and have a massage will have music on. And I have to use the line, well, it’s not for me because I’m a musician, which is not quite what I believe. And music inspires you. I think going back to the audiences thing, we should be incredibly proud of how special the experience is. That is not to say that we don’t want as many people as possible to experience that. But any company which diminished its product in order to get more sales would not last. And any company would say that the way to get more sales is to make your product even better. And that’s something which here at ENO is a very interesting discussion to have. Because Lilian Baylis, whom I talk about a lot as being fundamental to this company’s past, present and future, her view was not about accessibility as a goal, it was about the combination of accessibility and the highest quality of experience. So it’s not just that we want everybody to come to ENO, we want everybody to come and see how special opera is, the messaging of that, to use a 21st century term, is quite complex, but I’m really keen that we celebrate the fact that it’s a special occasion. It’s not about what you wear. People don’t ask when they go to the theatre what should they wear, but they are concerned when they go to the opera. Those are messages we can try to get across, that that’s a stereotype that is not relevant in this company. But the harder thing to make people realise is that special is special.

You partly do that by the sheer power of performance. I think people will generally shut up and listen if something is gripping.

Which is why I find the whole attitude from performers… It’s up to us to get people’s attention. The actors that famously walk to the front of the stage and tell people off for doing something unacceptable – of course we’re all frustrated when that sort of thing happens, but is it the right of the performer to tell people how to behave, other than how they are performing, forcing the concentration? Anybody can leave a phone on by accident, frankly. It’s not the greatest thing in the world. It’s far worse with someone who’s not engaged. And the engagement is our responsibility. And the reason I get upset with the coughing audiences – and I’m going to slightly contradict myself in what I said about the Shostakovich silences – is your consciousness that you failed that person’s experience, and that’s why it’s disappointing.

People used to remark on minute’s silences at the end – I remember when Rattle did Britten’s War Requiem in Bury St Edmunds – but minutes’ silences now are really frequent. They happen a lot here in the UK. And that is a lot to do with the authority of the conductor, just as not having people applaud between the third and fourth movements of Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique is up to the conductor.

I wrote in one of my blogs about how long is a piece? Because for a conductor, when does the music start? There’s this moment before the start which the conductor is unquestionably controlling. And that’s very easy to do, frankly. But what about the end of a piece? How long should that be and is it up to you to control it? Is it something that you can be part of. There’s one Beethoven symphony where there’s a pause marked on the silence, and I bet that’s never been heard.

I’ve seen several performances of Chailly’s Mahler where there’s a very loud ending, and yet people don’t break in with applause.

Because of how he’s done it. With Shostakovich Five, if there is immediate applause at the end, I think: I didn’t do that right, unquestionably. And the greatest thrill is to get to the end of Five or Ten and for that to happen. Then you know that people are spoken to, they get it. But as you say what’s interesting about the Proms and other concerts – not enough people go to London, but we are still lucky to live in a city where people are there because they want to be and therefore the experience is a very genuine and sincere two-way communication between the audience and the performers. I’ve been around a lot in the world, and – nowhere is as good as Tokyo, I would say. I was warned that it was about respect: it’s more than respect, it’s about engaging in experience.

Whereas I remember I was taking part in a Prokofiev-Shostakovich event at Carnegie Hall and Ashkenazy was conducting the Thirteenth Symphony, with Yevtushenko reading before the music started, but the general feeling was a low level restlessness all the way through. There wasn’t anything spectacularly awful happening in the audience, but it was disconcerting..

Apparently I have the record in [New York’s] Avery Fisher Hall for the number of people walking out, when I did Shostakovich’s Fourteenth with the New York Phil. I’m told that about 400 people left during it. I could tell there was a restlessness, but I didn’t really know until I got off stage and the two singers who’d been looking at them, [Yelena] Prokina and [Sergei] Leiferkus, were so furious that they said, if it happens again – there were four performances – if this happens in performance two, we’re going home. So I gave a speech to the audience before performance two, and I said, well, you’re about to hear 11 songs about death, and it’s going to take about an hour. And almost to a man, the entire audience looked at their watches. It was a fascinating thing to see that their dinner reservations, and all that they were going to do after the concert, were already on their mind. When does that mean I’m getting out, and should I go now, and do I really want to engage for an hour in death? The exit was considered an improvement that night, but why do you go to Shostakovich 14 in the first place, I’m all for curiosity…

It’s part of the social diary, I guess, or you have a subscription… we don’t for the most part have subscriptions here…

Which is both good and bad, one would die for the subscription because the security and the freedom that gives you is really special [Wigglesworth pictured right by Benjamin Ealovega]. But I was just talking to the box office manager here, whom I’ve known for years and years, and he was saying that across the arts more and more is last minute, so the box office finds it hard to know how things are going to be until then. Now although that is stressful, it’s actually thrilling, that people’s decision is, let’s go now, and it’s present tense existence, rather than, I bought my tickets for this six months ago and I didn’t realize Andy Murray was playing that afternoon…

Which is both good and bad, one would die for the subscription because the security and the freedom that gives you is really special [Wigglesworth pictured right by Benjamin Ealovega]. But I was just talking to the box office manager here, whom I’ve known for years and years, and he was saying that across the arts more and more is last minute, so the box office finds it hard to know how things are going to be until then. Now although that is stressful, it’s actually thrilling, that people’s decision is, let’s go now, and it’s present tense existence, rather than, I bought my tickets for this six months ago and I didn’t realize Andy Murray was playing that afternoon…

They invariably have standbys here, I know because a lot of my students would regularly go along at the last minute, but actually it did fill up. Even the Mastersingers did fill up – but how can you not sell out Wagner double-quick, especially when it was so ecstatically reviewed?

You only need 16,000 people, I think there were seven performances, and we need to engage in that question. If you can do work as great as that, as well as they did it, we need to absolutely ask ourselves: what could we, should we have done, what is this about?

Because even second-rate Wagner at Covent Garden sells, I think.

There is a Wagner audience, yes, thank goodness.

I was worried when there was that spell of three not good productions, and I’ve never seen the place so empty. That was the autumn of 2013.

What – Fledermaus and Fidelio?

And Magic Flute. Actually that sold well because it was Complicite, I hated it, sorry, but…

I would like to talk to you about why you hated it, not now but later. Because I’m doing the revival. I respect your views and I’m interested to know what you hated about it.

It’s such a good cast coming up. It was just for me very dark and serious throughout. Having seen that Parsifal at the Royal Opera in which Amfortas and the brotherhood were very sombre men in suits who went through this hideous ritual – I do think that whatever else is wrong in the world of Parsifal, that moment of ritual should have something enlightened about it. Similarly for me Sarastro and his brotherhood can’t just be creepy guys in suits.

That’s interesting, it was very successful in Amsterdam. And we have got a thrilling cast. And I wanted to do it because I think that having an orchestra visible onstage feels appropriate for the music director to be part of it.

No, I loved that.

But maybe after one of our chats on your course we can talk in more detail about it, because I think a revival has to be an opportunity to build on what was done the first time. And I suspect that Simon [McBurney], from his own attitude to the work, feels the sense of repetition in his life. Let's see.

- Book tickets for ENO's Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, opening on Saturday 28 September

- David Nice's blog on covering Lady Macbeth in depth in his Frontline Club lectures

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment