Is Wales really the land of song? | reviews, news & interviews

Is Wales really the land of song?

Is Wales really the land of song?

As Festival of Voice opens in Cardiff with Bryn Terfel, Charlotte Church and John Cale, a historian explains Wales's choral roots

Culture, said Aneurin Bevan, comes off the end of a pick. A hundred years ago there was no shortage of picks when a quarter of a million coalminers were employed in south Wales. By now the mines have gone but many of the choirs they created are still here, for the male voice choir is one of the distinctive emblems of Welsh identity.

The south Wales coalfield is the longest continuous coalfield in Britain and its choral tradition is just as unbroken. It began when the first tramload of the best steam coal in the world trundled out of the Bute Colliery in Treherbert at the top of the Rhondda Valley in 1855. The consequences were momentous. Within five decades the population of the Rhondda had soared from less than a thousand to 150,000, most of the work-force employed in the 56 pits that were sunk in close proximity to each other along the valley floor. The names of these collieries, some of them employing up to 2,000 men, still resonate like famous battles: Abergorki, Parc and Dare, Tynewydd and Lewis Merthyr have the Napoleonic ring of Austerlitz, Jena and Borodino.

The choir was an assertion of working-class male bonding, of harmonious fellowship

Immigrants flooded in from the rest of Wales and beyond to cut and transport this black gold so that by 1900 the Bristol Channel was as significant to the world economy as the Persian Gulf is today. Most of these migrants were young single men who on arrival took lodgings where they were given the room next to the front door. After work they went through it in search of recreation and the company of young men like themselves. Men outnumbered women by a ratio of 10 to 8 in the Rhondda, and this accounts for much of the masculine culture that is still a feature of the valleys today. Their fondness for boxing, rugby, football, the brass band, the working men’s club and the male voice choir persists, even if the industrial flood tide which gave rise to them has now receded into history.

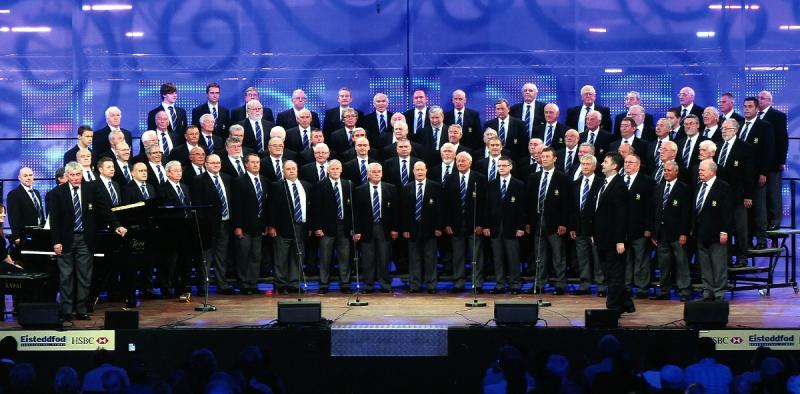

This was an industry that bred pride in men’s manual skill and loyalty to the collective institutions that represented them – the Miners’ Federation, the lodge, the institute, the rugby team, the band, and the choir; especially the choir. The choir was an assertion of working-class male bonding, of harmonious fellowship. And just as Welsh steam coal achieved world-wide recognition so did its choirs. The Rhondda Gleemen (pictured below) won first prize at the Chicago World’s Fair Eisteddfod in 1893; two years later their great rivals from Treorchy were invited to Windsor Castle to sing in front of Queen Victoria, the first of many to receive the royal command. Soon they would be singing at the White House too.

They were nearly all miners. At the coal face the work was unremitting, the dust and heat suffocating, and the casualty rate from roof falls and runaway trams exceeded only by the horrific explosions of gas and fire damp that claimed 290 lives at Cilfynydd in 1894, 119 at Wattstown in 1905 and 439 in 1913 at the Universal Colliery, Senghenydd. The south Wales coalfield was the most dangerous in Britain. These were circumstances that bred faith and fellowship. This is reflected in the repertoire of the Welsh male choir today, for it has changed little over the years: dramatic opera choruses, melancholy part-songs and rousing hymns.

They were nearly all miners. At the coal face the work was unremitting, the dust and heat suffocating, and the casualty rate from roof falls and runaway trams exceeded only by the horrific explosions of gas and fire damp that claimed 290 lives at Cilfynydd in 1894, 119 at Wattstown in 1905 and 439 in 1913 at the Universal Colliery, Senghenydd. The south Wales coalfield was the most dangerous in Britain. These were circumstances that bred faith and fellowship. This is reflected in the repertoire of the Welsh male choir today, for it has changed little over the years: dramatic opera choruses, melancholy part-songs and rousing hymns.

But why sing at all? For one thing the consonantal character of the Welsh language, like Italian and German, lends itself to clearly articulated expression. When the rural migrants poured in to the mining valleys they brought with them their traditional culture, their language, their nonconformist religion, and their fondness for lusty congregational singing. In their unfamiliar new surroundings, they found solace and sociability in song, for in a materially poor society the voice was the most democratic of instruments; it cost nothing, as even the cloth-eared have a larynx.

Men and women found comfort from the daily industrial grind in their nonconformist churches which were opening in Wales at the rate of one a week throughout the 19th century; by 1900 there were over 5,000 of them, over 150 in the Rhondda alone to complement the 50 collieries, dominating both the skyline and the social and cultural life of the people. They were places of song as well as worship. This was where choirs took shape, rehearsed and performed, for where else was there? In the early industrial years, before welfare halls and workmen’s institutes were built, they were also the people’s theatres, their venue for entertainment.

The chapel and the colliery are the key institutions in the history of the Welsh male choir. Chapels in Wales are closing at the rate of one a week; King Coal will never recover his throne. But his choral legacy lives on.

- Festival of Voice runs in Cardiff from 3 to 12 June

- Gareth Williams is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of South Wales. His book Do You Hear the People Sing? The Male Voice Choirs of Wales is published by Gomer at £14.95

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bach’s B minor Mass, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin - everything human and divine

Perfect ensemble runs the gamut of a supreme masterpiece

Bach’s B minor Mass, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, Christ Church Cathedral, Dublin - everything human and divine

Perfect ensemble runs the gamut of a supreme masterpiece

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James’s Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James’s Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Add comment