David Hockney RA: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life, Royal Academy | reviews, news & interviews

David Hockney RA: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life, Royal Academy

David Hockney RA: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-life, Royal Academy

An ongoing series of portraits has served as a tonic during difficult times, but its value is more personal than artistic

The opening image of this new David Hockney exhibition – a sketchily painted portrait of a seated man, slumping heavily forward, his head buried in his hands – could be a portrait of Brexit despair.

In this sense, this opening portrait, dated precisely 11th, 12th, 13th July 2013, can also be regarded as a self-portrait, the agitated hatching of the background and discordant zig-zag pattern of the rug illustrating Hockney’s and J-P’s shared state of wretchedness, while the composition (perhaps unconsciously) echoes Van Gogh’s Sorrowing Old Man.

The contrast between the grief-stricken figure, the dazzling Californian colours, and the rapid execution, however, sparked a new idea. Hockney embarked on what would be a more public cycle of intimate portraits, each using the same 48” x 36” upright canvas, each produced over a similar timeframe (the precise dates are included in the titles), and each using the same coloured backdrop. A second portrait of his close friend Bing McGilvray, whose bulky form fills a canvas that can’t quite accommodate him, illustrates Hockney’s maxim about portraiture, that one can never "quite get the whole person".

The contrast between the grief-stricken figure, the dazzling Californian colours, and the rapid execution, however, sparked a new idea. Hockney embarked on what would be a more public cycle of intimate portraits, each using the same 48” x 36” upright canvas, each produced over a similar timeframe (the precise dates are included in the titles), and each using the same coloured backdrop. A second portrait of his close friend Bing McGilvray, whose bulky form fills a canvas that can’t quite accommodate him, illustrates Hockney’s maxim about portraiture, that one can never "quite get the whole person".

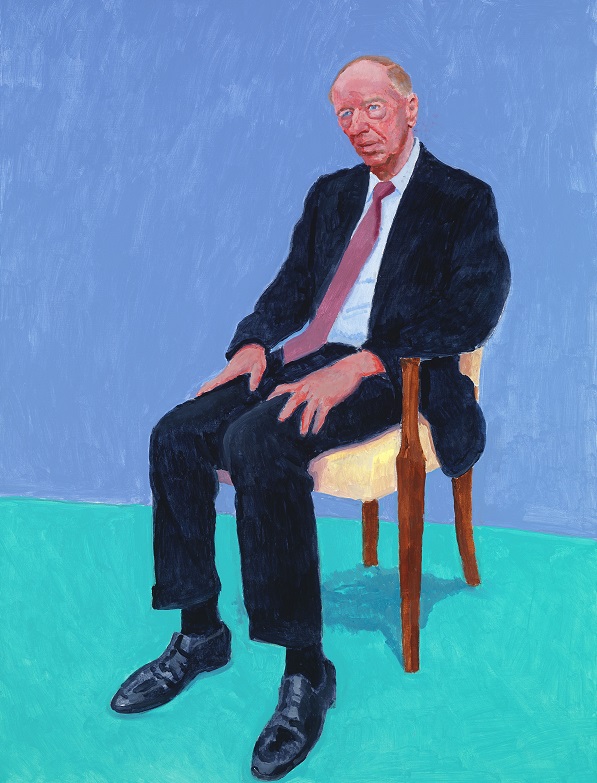

After 10 more works the idea of a series crystallised, and the project is still ongoing. The subjects are Hockney’s surrogate family of friends and intimates (many of them art world luminaries), some of his own family, and a few children of friends, all painted over three days (not too onerous for the sitter – one day off work and a weekend, as Hockney suggested – although busy folk like Jacob Rothschild (pictured above right) and Larry Gagosian could only spare two).

So now we have 82 portraits – and (rather coyly) one still-life – all drawn in charcoal directly on to canvas and then built up in acrylics in the same methodical way, during seven-hour bursts of activity. Clearly Hockney has turned to ritual as an aid to recovery and artistic reinvention. Only the first portrait displays any raw emotion, but all share scale (the exception is a double portrait of twins), a turquoise-green and blue ground, and the same simple chair with its butter-toned upholstery. The chair was positioned on a platform, so that the eye-level of sitter and artist matched, and the light is unvarying (all were painted in Hockney’s LA studio).

This is the undoubted strength of the project and exhibition – the series is presented as one coherent whole, rather like a giant Pop collage. The Academy has hung the works uniformly against a rich Venetian-red backdrop, the room colour normally reserved for Old Masters. This makes the colours zing, and gives the pictures maximum formal and colouristic impact.

Hockney has worked from life, relying on the decisiveness and immediacy of the drawn line. This gives the series a freshness, a sense of real time, and a strange mute energy that could never quite be captured by a photograph. We know that Hockney is gregarious, but also very deaf, so that although he loves parties he now prefers intimate one to ones. This series provides him with that opportunity on a continual basis, although the process of painting is intense and largely silent. Thus Hockney responds more to body language than features animated by exchange.

Hockney has worked from life, relying on the decisiveness and immediacy of the drawn line. This gives the series a freshness, a sense of real time, and a strange mute energy that could never quite be captured by a photograph. We know that Hockney is gregarious, but also very deaf, so that although he loves parties he now prefers intimate one to ones. This series provides him with that opportunity on a continual basis, although the process of painting is intense and largely silent. Thus Hockney responds more to body language than features animated by exchange.

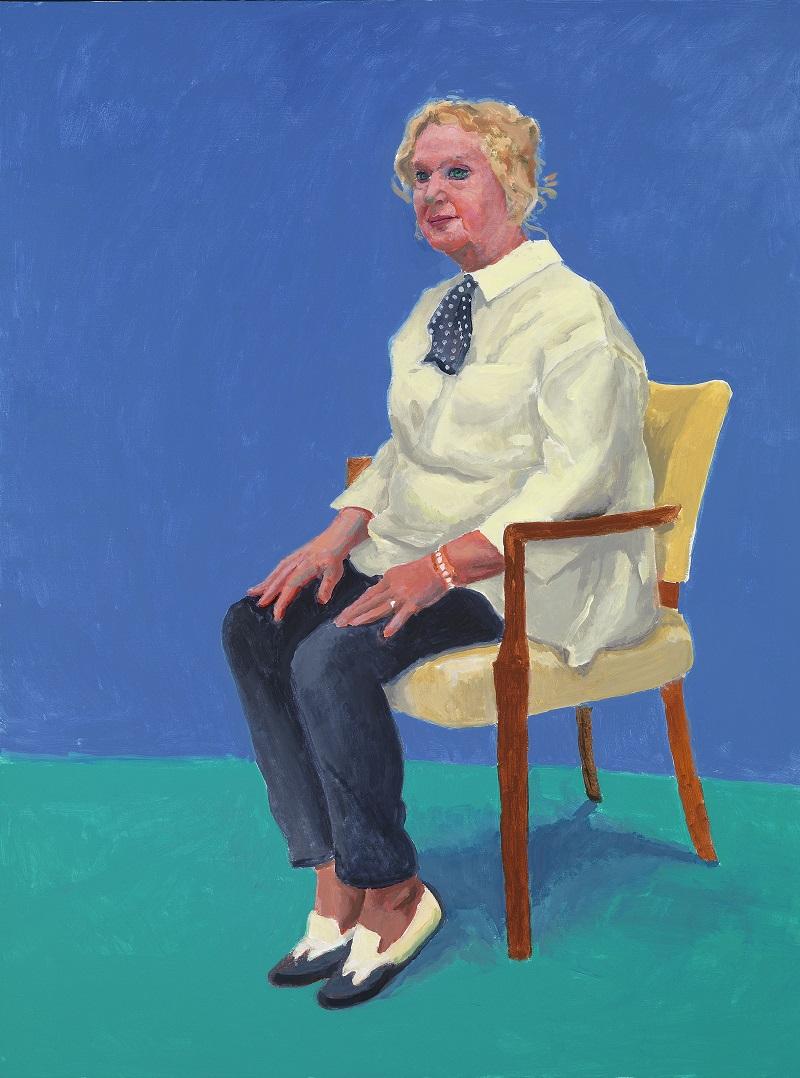

The exhibition has an undoubted impact, due largely to its Pop splash of colour and its repetitive nature. The eye naturally searches for rhythm and variations among the ruddy-faced sitters, provided largely by the way they occupy the chair (one slings his leg nonchalantly over the arm) and the variety of clothes they have chosen for the occasion: the glint of Larry Gagosian’s expensive watch; the shiny black shoes of Jonathan Mills; the billowing red taffeta of Rita Pynoos’s skirt (pictured above left). The still-life of fruit and vegetables, against the same background, provides a humorous counterpoint.

But by half way, I’m flagging; I am distracted by the flatness of many of the characterisations and the unevenness of Hockney’s handling of the acrylic medium (including the new gel acrylic that he is learning to use). There is the occasional portrait that really grabs: I particularly liked the detached portrait of 11-year-old Holden Schmidt, who was apparently resentful at sitting during his school holidays. Another portrait that triumphs against the odds is that of 73-year-old Celia Birtwell (once Mrs Clarke), the subject of many celebrated Hockney portraits. Here there is a real sense of shared history and intimacy over decades (main picture).

The rather splendid book that serves as an exhibition catalogue, shows Hockney standing with a montage of all 83 paintings, demonstrating that he wants this series to be regarded as a single body of work. He also believes that "The 20-hour exposure is not only visual. These people are revealed." Whether he has succeeded in both respects is questionable. For Hockney, however, it is clear that this return to the portrait format he loves has brought creative renewal and a welcome burst of sanity.

- David Hockney RA: 82 Portraits and 1 Still-Life at the Royal Academy until 2 October

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Photo Oxford 2025 review - photography all over the town

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Add comment