theartsdesk Q&A: John Lydon | reviews, news & interviews

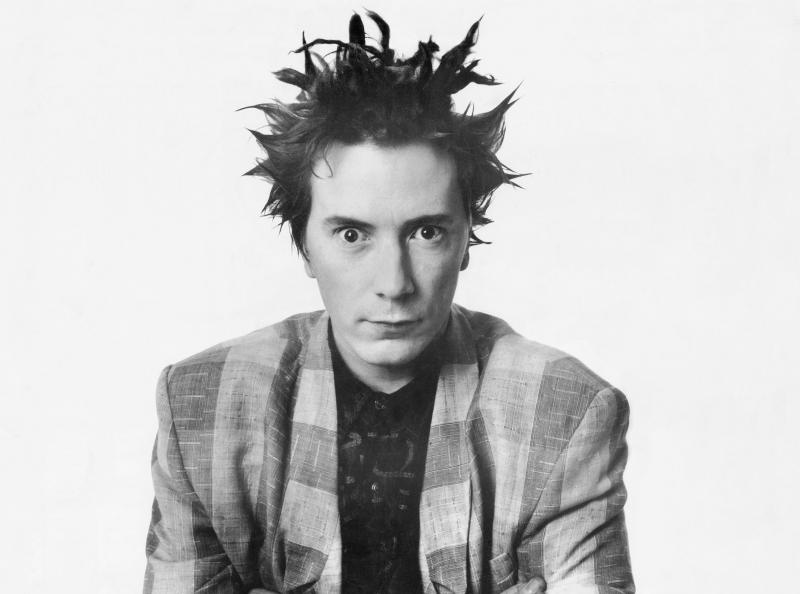

theartsdesk Q&A: John Lydon

theartsdesk Q&A: John Lydon

Here's Johnny: the PiL singer lifts the lid on 'Metal Box'

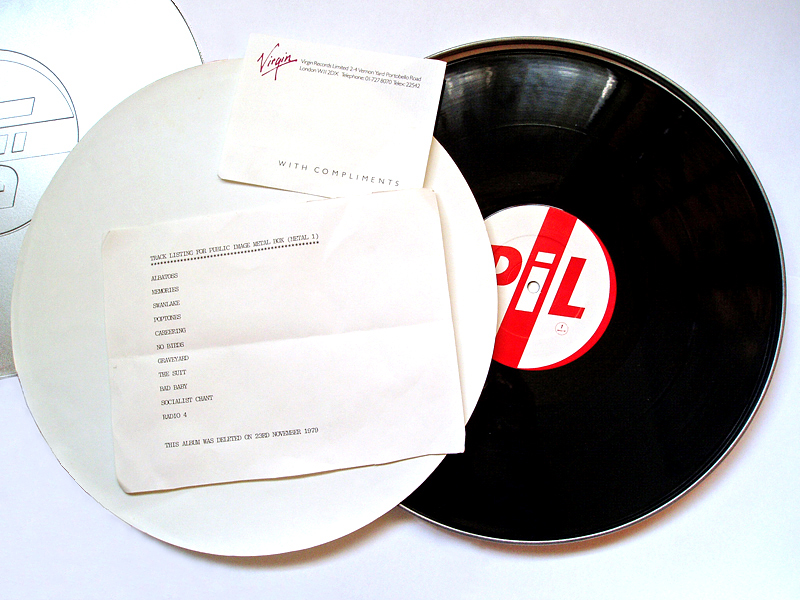

It was first released on 23 November 1979, comprising three 45rpm, 12in records housed in 16mm metal film cans, and then reissued the following February as Second Edition, in the more friendly and familiar format of a double album, 33rpm, gatefold sleeve, lyrics on the back, no song titles, with just the PIL logo on the record label.

Thirty-six years later, and already enjoying a healthy digital afterlife in the reissue department, John Lydon has overseen a new Super Deluxe Edition of both Metal Box and the 1986 album, Album. Each one has expanded to a four-disc set, in vinyl and CD editions, featuring unreleased live and studio tracks, plus the usual high-end box-set accoutrements – poster, book, art prints, postcards.

Talking from his home in LA, it's clear that Lydon's close involvement in the project reflects his commitment to some of his finest ever music, and to that music's audience. It's also a fair guarantee of not being cheated by the shoddy or the second-rate. Talking about Metal Box's turbulent, inspired creation in the tail lights of the 1970s, or the pleasures of working with Ginger Baker and Tony Williams on Album, Lydon is clearly proud of the music's enduring longevity and power, passionate about how it should sound and how it should be heard – and as marvellously unrepentant as ever.

TIM CUMMING: How involved have you been in these reissues?

JOHN LYDON: You have to make sure it’s of the highest quality, and I’m always very involved in the art work so that it doesn’t get bastardised. People come to you with these offers and ideas and you think it’s going to be easy, but it isn’t. You have to monitor every single aspect of it, and it takes up an awful lot of time. It’s a worthy cause. These were excellent records, not only in their time, but now.

How was Metal Box conceived – as a soundscape it’s of a piece, in the way Bitches Brew or On the Corner are.

I’ve made that connection myself and I understand what you mean by that, but we didn’t have the luxury of a full-time studio, so there were lots of bits and pieces done all over the place. But particularly the Virgin one on Goldhawk Road. If it had spare time after the major acts left, we’d just zip over. And spend most of the afternoon and late evenings sitting around twiddling our fingers waiting for the opportunity. We were messing about on old keyboards at the time, an old Yamaha I had, trying to get a set together. We could never do more than one or two songs a night. It’s amazing how we kept a continuity in the sound and approach, knowing all those distractions going on – but we did. And a major distraction of course was our own internal squabbling [laughter].

Did that discord and tension help at all?

Did that discord and tension help at all?

No. I’d had experience of that with a previous band, but I never wanted PIL to be that way, but you can’t help it. Personalities sometimes clash, you know – you’ve just got to wait for people to sort themselves out. But sometimes that can add an intent into the recording itself that is impossible to imitate, once you get that uh – shall we call it spite? [laughter] Once you put some reigns on it you can ride it into the groove properly. The cause is bigger than any individual argument, and therefore – hello, chaps. And that was usually the conclusion.

There was a group mind going on?

Yes, very much so. Always. And I never take that away from anybody. We had a serious level of respect for each other. Made none the easier by record company involvement. They were continuously trying to turn up at the studio and offer advice, which in them days was always under the sentence, "Can you write a hit single?" [laughter]. Whatever that was supposed to mean. I think by the time of Metal Box I had a history of writing hit singles. I certainly didn’t need no advice. I wanted this to be a far different, more challenging landscape. And I think I was proved right, in the end. By taking the risks we did we made the better records.

Metal Box is far out and very challenging, especially compared to anything around that time – or anything now...

I think it’s as powerful – or more so – as Never Mind the Bollocks in terms of its influence. Whatever doors we opened up in the Pistols, with Metal Box we shattered the entire framework of the housing [laughter]. It was very good fun. I remember at the time I was asked to describe the music and I said it’s a runaway truck going down a hill with no brakes. Deliberate, not too fast – hence, it’s a truck – but none the less dangerous. And thrilling working with people who weren’t known, who weren’t famous. It was the first time in my life I could "get back to my roots."

Whatever doors we opened up in the Pistols, with 'Metal Box' we shattered the entire framework of the housing

What kind of records were on your player when you were making the album?

Oh, everything. I’m always limited in the jazz world because I find too much of it phoney, but Miles Davis is always going to be there, Ornette Coleman is always going to be there. Sun Ra, and a few other odds and sods. A lot of folk music from all around the world. Reggae, a consistent friend of mine. And of course pop records. I don’t like the way the Top 30 is manipulated, but every now and again there’s a real gem in there. I like the easy flow of a pop production. You can say an awful lot in as few words as possible. Very nice territories to explore. It was the first thing we ever did as Public Image, the song itself, which was the first thing we rehearsed, and that came out automatically. That set us on our way. "We’re onto something good here." That was the bond that tied us.

There’s such leap form the first PIL album to Metal Box.

That came about very instinctively. There never, ever is anyone sitting around dictating, "this record is going to sound like…" It evolves itself instinctively.

What kind of folk music were you listening to? British, American?

I could go all over the world, but American folk, normally no. I’m sorry, but that 60s revolution from New York folk music never meant anything to me. It was a little too perfected. It left me cold. It wasn’t coming from real folk, it was coming from pretentious arseholes, most of it, with very few rare exceptions. Who can knock Joni Mitchell, for instance? You can’t, she’s bloody perfect. Same with Carol King. Perfect. But the rest with their frumpy hats and farming implements, no, I’m not interested. Steelye Span was more me, and Fairport Convention.

In terms of the remastering of Metal Box, how do you keep that original 12in bass sound?

Well, that’s a process in itself because you’re fighting an industry that wants to manufacture as cheaply as possible as many units as they can. Our way, and this has always been a PIL thing, is to give you the most sound quality you can, regardless of the cost. That’s an uphill battle in itself. I don’t do this to save money. I’ll save costs for the listener. I’ll dig into me own pockets when I feel it’s necessary. We don’t make this textured landscaping, which is what our music is, for it to be reduced to a picture postcard.

So it’s the same arguments with record companies today as it was then?

Continuously and consistently, that’s the bottom line. It’s in that area that I earned a reputation of being difficult to work with. Because I do insist on quality, Why would I be doing this otherwise? For nonsensical, vague misrepresentations of the thing. That’s why the internet infuriates me. If you listen through the internet, the sound is never going to be there. The set-up is against you right from the start, so my automatic recommendation is vinyl, and if that’s not affordable, go to CD. Listening on the internet, so many of the dimensions are missing, it’s cheating yourself. And Metal Box is a very difficult album to make, because of the amount of bass we wanted to flood it with. And engineers in the studio, so many rows with them! "Oh that’s just not technically possible. Something will have to give." Well, bring down the vocals. [laughter]. And bring up the bass. I want to hear bass. The bass is what we’re trying to base all this on. It’s the selling point of the sound. You could call it early drum 'n' bass. And with, to my mind, the most astounding guitar playing I had ever heard, which was Keith. We’re far from friendly with each other, but hey, I’d never ever knocked my respect for him. What he was capable of was incredible and so thrilling to work with. We all brought different gifts to the tea party. The chimps' tea party [laughter].

'Metal Box' is a very difficult album to make, because of the amount of bass we wanted to flood it with

Metal Box came out in November 1979 – Mrs Thatcher had just come to power. And 36 years later, we have Mrs May, Brexit and the return of grammar schools…

Well, here she is challenging everything we really know about what works or doesn’t in the world. She wants to bring back that old school system. Creating this us-and-them attitude. Hello? That’s what got the country into such problems. You’re still not learning to treat everyone equal. Everyone deserves the right to equal-opportunity education as well as welfare. And that does not make me a socialist. It makes me a common sense person who cares for his other human beings. This is the unfortunately duality of the world. Us and them. Metal Box is quite clearly "all of us!". It was equal opportunities as far as publishing went, too. I could quite easily have grabbed every penny and run off with it, but no, I wanted to treat my fellow human beings with respect.

With Public Image, it was also a process and a product, rather than a star band.

We had fabulous big ideas about using the idea of a corporate logo to represent anti-corporate feelings.

With Metal Box coming out again now, it seems to be still pointing to the future, it seems as relevant as it was then.

Well, let me explain: at the time, when I plonked that on the counter at Virgin Records, and said, there you go, enjoy, they were in no mood for it. Could not make hide nor hair of it. And for me that is a very pleasing, good result. If you’re not creating shock and awe, what’s the point? When you’re young you’ve got to take risks. You can’t afford to be lulled into mainstream activities, or you’ll be quickly lost on the conveyor belt of sellability. Very dangerous things to be taking on, but we reaped the rewards, eventually. Personally it’s cost me small fortunes, because I had to invest in PIL to keep it running. A nice little reminder to my fellow compatriots at the time: "You want to share the spoils? Come and share the debt!" [laughter].

There’s an unissued live set included, from Manchester in 1979?

There’s an unissued live set included, from Manchester in 1979?

Which was very difficult, because we went through so many bleedin’ drummers. There was some kind of situation going on there between the bass and the drums. We had such an excellent drummer in Jim Walker, we then found it difficult to keep up with that. The tension was there – I’m always standing up for the disenfranchised, and I wanted to make the best of that situation, but it turned out to be daft, and there it goes. But that is what PIL is, it’s a school of learning, We’re all learning all the time.

It sounds like a bit of a laboratory on stage.

It is. And it’s a chemistry experiment, too, behind the stage [laughter]. Trying to get the right balance of personalities.

In the long list of PIL drummers, there’s Karl Burns from The Fall.

Yeah. Yeah. He was around and there it goes. We needed someone to do Top Of The Pops. You grab whatever’s available. It’s a mixed bag out there, there wasn’t exactly huge amounts of money being thrown at us. Anything that could possibly work would work. The ideas were bigger than any importation into us. Again it’s a risk.

Do you ever cross paths with Mark E Smith?

No. I seen him a few years ago, I think he was a bit worse for wear, shall we say, at the Q Awards, and I was far from sober. That was about it. But there’s a man who’s relentless – he’s miraculous in many ways. Here’s a man working inside this one song idea, which he’s finding new and different inflections for, continuously. It’s an obsessive work that he creates, but it’s thrilling. You can drop in and out of it, leave years in between, and it’s almost like there’s a safe guarantee of something familiar there. Of course, that’s as different to me as you could possibly hope to get, but that don’t mean that I don’t respect other people’s approaches. Far from it.

It was a fantastic creative time. My record collection at that time really swelled

And from the same period, Genesis P Orridge – he’s making music again.

There’s some rare talent going on in that brain. It was a fantastic creative time. My record collection at that time really swelled [laughter]. People were picking up on the idea that you don’t have to follow a routine, you don’t need a format, and great things came from that. What we were doing was making it vibrant and interesting and thrilling again. The Pistols created a punk audience for you, and I go into PIL and create an entirely new audience all over again. And listened to by people who want to be in bands themselves, and create things that only add to the textures and flavours that make us human beings so relevant. We find these delicious ways of communicating with each other, and music is the one I’m most involved in.

With you and PIL it’s a much broader reach – from Metal Box, a few years later you’re working with Afrika Bambaataa.

That came about because I like the way he mixed his records live. Funkadelic, then a Kraftwerk track, then some insane ACDC track. He’d found ways of blending the grooves together, and that was lovely. A universal appreciation of all the different approaches to music. We met, we got together, there wasn’t much happening at the time, PIL was in a state of fracture, so I went in to the studio with him. That’s where I met Bill Lazwell, which later evolved into Album. That was the result of taking a mad dash and, dare I say it, interesting cowboy risks. From that Bambaataa track, the world of rap became an issue.

It seems a very timely track now, as if it could have been written last week.

It seems a very timely track now, as if it could have been written last week.

It’s bang on, isn’t it? Shocking, shocking. Small ladders lead to, well snakes. If you’re not careful. That’s what led to working with Leftfield on “Opening Up” [1995]. It’s about opening that door to different trains of thought that could meet on the same track.

You’re doing some dates in the UK soon.

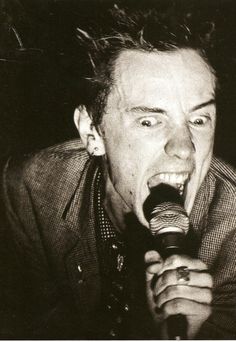

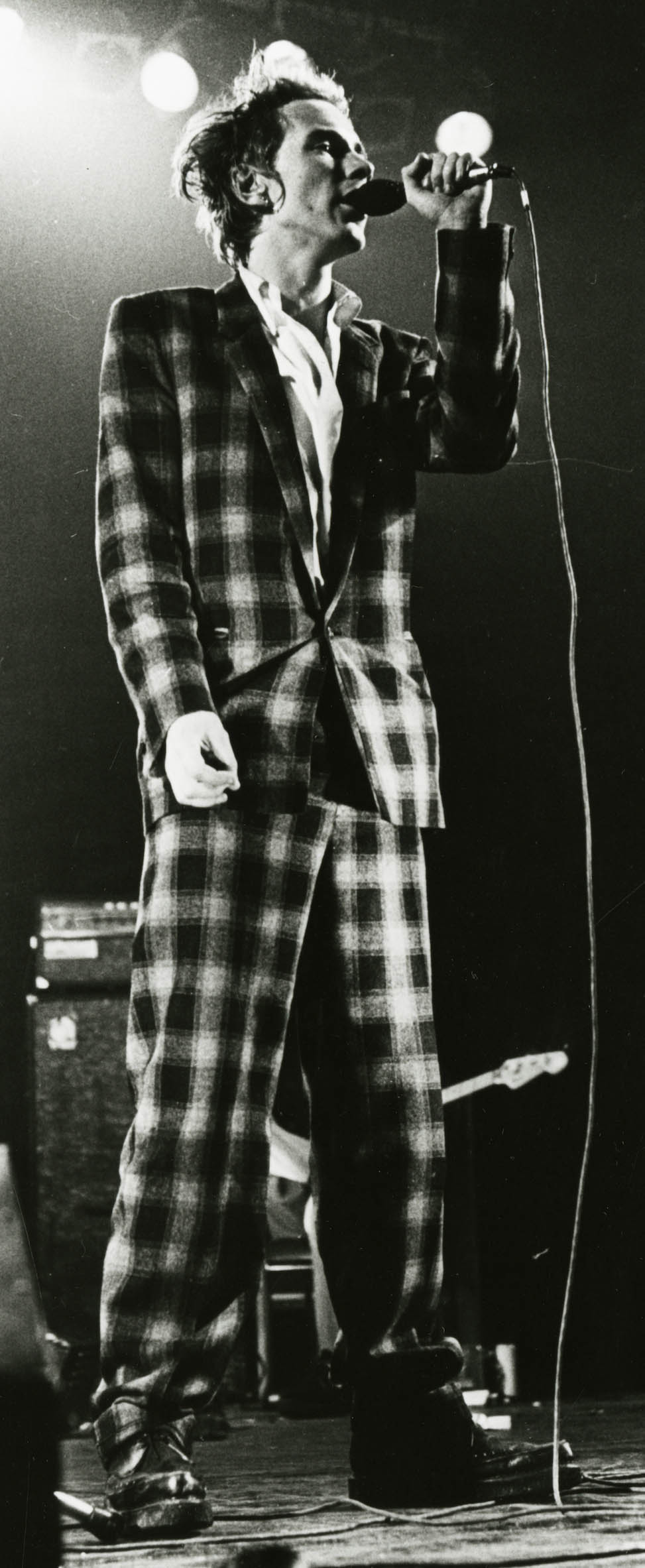

Yes, these are warm, intimate places we’ve picked. I don’t need stadium rock. I like up-close and personal. In the wonderful world of music I was thrown into, I had to very quickly get over my shyness, so now for me, eye contact is vital, for the concert to work. The audience, they feed you the energy back. You can feel what it is they’re thinking, in their eyes, and that shape-shifts the songs amazingly well. That’s what I mean when I describe PIL as a folk band. We share this with the folk, and we’re the same folk ourselves. We’re looking for that direct connection.

Will you draw much from Metal Box on this tour?

An awful lot of it will be led by the last two albums, and of course newer ideas are creeping in, and we’re thinking of shape-shifting them songs. But it’s all different pieces of the jigsaw puzzle that blend well together, and take your brain off into different directions, and hopefully entertaining not only your feet but your minds also.

With Album, what was it like having Ginger Baker behind you?

Let’s face it, he’s one of the world’s greatest drummers and greatest personalities. He’s as mad as they come [laughter]. I found him great fun to work with. Just watching him dismantle drum kits, basically, his approach to it. With all the capability and sensibility of rhythmic pattern and structure that you could ever ask for as a singer. But then different drummers bring different things to the table. Tony Williams was there, too. Stunning, equally brilliant in a completely different way.

There were many jazz people, especially when we moved to New York, who were fascinated by what we were doing, sound-wise. They wanted to know if we were following a train of thought or a rule book, or a manifesto – which is what jazz musicians tend to do. Nope, it’s all spur of the moment, instinctive. Which opened up a lot of their eyes as to where jazz was going wrong.

One of things that used to horrify me most – the Japanese are brilliant at this – was that they can duplicate note for note a very complicated jazz album, but it will be completely soulless because of that. It lacks the originality and looseness of the original concept. So that’s the damage that can be done, by over-elaborating grandiose thoughts into what should be seen basically as the flippancy of music. It’s the temporariness of it that thrills me; that you’re never, ever going to be able to do it the same way twice is even more thrilling. Because why would you want to? There’s my drive.

Ginger briefly toured and recorded with Hawkwind; weren’t you a fan?

Aah, well I used to follow Hawkwind, when I was young. Whenever I knew they were gigging, and festivals in particular, I’d always zoom off, and bunk on the train and go off up there, usually alone. They had a family type of affair wrapped around them, at the same time they had a biker crew [laughter]. We all had similar interests. I was very young for them, I suppose. I wasn’t one for back-stage hanging out, so don’t get me wrong, saying that. I was out front, me. I came for the music, not the social scene.

Going back to Metal Box, is it a confessional album?

Well, I hope so. I’m tearing myself apart and researching what motivates me as much as I am anything else. That’s very important. You see, for me the Pistols were never an attack on individuals, it was an attack on institutions and governing bodies that dared presume they had the right to tell us what to do without our involvement. PIL was inner research and finding out what was wrong with myself, and correcting it. Putting myself in a position of strength when I looked at the actions of others. Always to be accurate, that’s my dream. To tell it like it really is, to tell it as you really see it, and to not be just plain damn spiteful. Or bitter or twisted, which a lot of people end up doing, That’s a pity. That’s how you wreck your own life, when you hold bitter resentments. Sorry Donald, but that’s what Mr Trump is up to at the moment. [laughter] He’s a classic example for me of how I never ever want to be. At the same time I can analyse him and realise how easily all of us have the capability of turning into him in a heartbeat. And to know that and to have that sense of empathy with people, even if they’re extremely negative – if you research this in yourself, you’ll find solutions for human problems.

The Pistols were never an attack on individuals, it was an attack on institutions and governing bodies that dared presume they had the right to tell us what to do without our involvement

At the moment there is a lot of division in the world.

There is, and it is pointless and futile. I don’t like playing festivals too much because a lot of the bands are very oppositional. They take this "us and them" attitude and there really isn’t any of that sharing stuff that I used to know, that rock festivals were famous for. The generosity. If you were freezing, someone would give you a blanket. They seem to be working against that "we’re all in this together" principle.

So the “us and them” principle of the old power structures has gone internal, into rock band culture?

Yeah, into band warfare. It’s there, it exists. At the same time, so many bands are delightful company. You can’t win the whole world; the few who share the enjoyment of being alive with you is good enough to get you through.

As I try to indicate, the more research you do internally – and you don’t need an analyst for this, because you are your best analyst inside yourself – the more you’ll realise you can be calm about other people’s mistakes. For me there’s one basic bottom line. If you lie to me more than three times, in a row, that’s it. I can’t be doing with you. That’s a correct driving force in life. You can’t have people abuse you with lies. It’s very important. From when I was very young, that major horrible illness that took my memories away for so long, it was really important for people to tell me the truth, and that has stuck with me ever since. There you go, I’m difficult to work with because I demand to tell it like it is.

I guess you could see PIL and Metal Box especially as a truth laboratory. Internally, and between members.

It really is, yeah. And I think you can read that in the songs, the lyrics quite clearly indicate that. For me, when I go back and listen to it, it’s an astounding tour de force, and I am really impressed we kept ourselves bonded there for that length of time, to make such a massive statement.

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more New music

Album: Solar Eyes - Live Freaky! Die Freaky!

Psychedelic indie dance music with a twinkle in its eye

Album: Solar Eyes - Live Freaky! Die Freaky!

Psychedelic indie dance music with a twinkle in its eye

Album: Night Tapes - portals//polarities

Estonian-voiced, London-based electro-popsters debut album marks them as one to watch for

Album: Night Tapes - portals//polarities

Estonian-voiced, London-based electro-popsters debut album marks them as one to watch for

Album: Mulatu Astatke - Mulatu Plays Mulatu

An album full of life, coinciding with a 'farewell tour'

Album: Mulatu Astatke - Mulatu Plays Mulatu

An album full of life, coinciding with a 'farewell tour'

Music Reissues Weekly: Sly and the Family Stone - The First Family: Live At Winchester Cathedral 1967

Must-have, first-ever release of the earliest document of the legendary soul outfit

Music Reissues Weekly: Sly and the Family Stone - The First Family: Live At Winchester Cathedral 1967

Must-have, first-ever release of the earliest document of the legendary soul outfit

Album: Robert Plant - Saving Grace

Mellow delight from former Zep lead

Album: Robert Plant - Saving Grace

Mellow delight from former Zep lead

Brìghde Chaimbeul, Round Chapel review - enchantment in East London

Inscrutable purveyor of experimental Celtic music summons creepiness and intensity

Brìghde Chaimbeul, Round Chapel review - enchantment in East London

Inscrutable purveyor of experimental Celtic music summons creepiness and intensity

Album: NewDad - Altar

The hard-gigging trio yearns for old Ireland – and blasts music biz exploitation

Album: NewDad - Altar

The hard-gigging trio yearns for old Ireland – and blasts music biz exploitation

First Person: Musician ALA.NI on how thoughts of empire and reparation influenced a song

She usually sings about affairs of the heart - 'TIEF' is different, explains the star

First Person: Musician ALA.NI on how thoughts of empire and reparation influenced a song

She usually sings about affairs of the heart - 'TIEF' is different, explains the star

Album: The Divine Comedy - Rainy Sunday Afternoon

Neil Hannon takes stock, and the result will certainly keep his existing crowd happy

Album: The Divine Comedy - Rainy Sunday Afternoon

Neil Hannon takes stock, and the result will certainly keep his existing crowd happy

Music Reissues Weekly: Robyn - Robyn 20th-Anniversary Edition

Landmark Swedish pop album hits shops one more time

Music Reissues Weekly: Robyn - Robyn 20th-Anniversary Edition

Landmark Swedish pop album hits shops one more time

Album: Twenty One Pilots - Breach

Ohio mainstream superstar duo wrap up their 10 year narrative

Album: Twenty One Pilots - Breach

Ohio mainstream superstar duo wrap up their 10 year narrative

Album: Ed Sheeran - Play

A mound of ear displeasure to add to the global superstar's already gigantic stockpile

Album: Ed Sheeran - Play

A mound of ear displeasure to add to the global superstar's already gigantic stockpile

Add comment