Howard Davies: An Appreciation | reviews, news & interviews

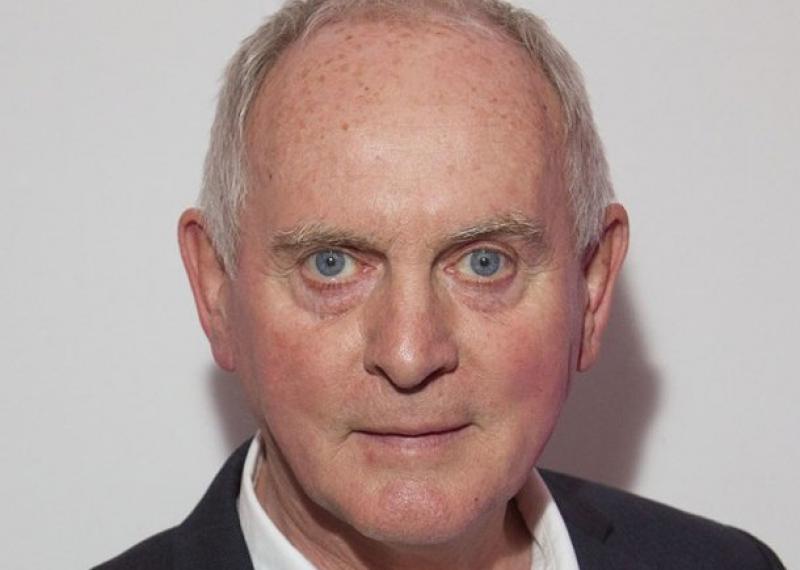

Howard Davies: An Appreciation

Howard Davies: An Appreciation

The peerless directors' director cast a spell over audiences across the repertoire

Howard Davies, the theatre director who has died at the too-early age of 71, may not have achieved the renown of many of his colleagues. He didn’t direct blockbuster musicals, rarely ventured into TV and film, and didn’t possess the signature style that gets you noticed – and wins awards – early on.

But Davies was what one might call a directors' director: a wide-ranging talent who approached text from the inside out with a clarity, vigour and breadth of vision that are pretty much without peer. I saw my first Davies production in New York in 1981, when his London staging of Pam Gems’s Piaf crossed the Atlantic, winning its then unknown leading lady, Jane Lapotaire, a Tony Award over the likes of Elizabeth Taylor. (No one looked as shocked as Lapotaire, whose acceptance speech is worth watching on YouTube.)

And as recently as last December, I was held spellbound by Davies’s gifts, on that occasion with a Hampstead Theatre revival of Tom Stoppard’s 1988 espionage-themed drama, Hapgood, that exhibited the quiet bravura on which Davies staked his brilliant career (pictured: Lisa Dillon in Hapgood. Photo by Alastair Muir.) In between was a CV devoted both to new plays (The Secret Rapture) and classics (a brilliant Crimean-era Troilus and Cressida for the RSC), canonical masterworks (Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, his scorching All My Sons) with lesser-known titles from great writers (Hapgood, for example) that, under Davies’s enquiring eye, seemed newly reclaimed. (Pictured below, Zoe Wanamaker and David Suchet in All My Sons. Photo by Nobby Clark.)

And as recently as last December, I was held spellbound by Davies’s gifts, on that occasion with a Hampstead Theatre revival of Tom Stoppard’s 1988 espionage-themed drama, Hapgood, that exhibited the quiet bravura on which Davies staked his brilliant career (pictured: Lisa Dillon in Hapgood. Photo by Alastair Muir.) In between was a CV devoted both to new plays (The Secret Rapture) and classics (a brilliant Crimean-era Troilus and Cressida for the RSC), canonical masterworks (Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, his scorching All My Sons) with lesser-known titles from great writers (Hapgood, for example) that, under Davies’s enquiring eye, seemed newly reclaimed. (Pictured below, Zoe Wanamaker and David Suchet in All My Sons. Photo by Nobby Clark.)

Small wonder Nicholas Hytner insisted on Davies as a first among equals when Hytner was handed the National’s reins: accustomed to working with stars – and major ones at that – Davies always put whatever play it was first, at the possible expense of announcing himself as a directorial star. That made him a magnet for talent even as he returned the industry-wide affection with generally unerring taste.

In so doing, of course, he became a leading light, or star, largely by finding the human pulse and heartbeat to the play at hand. It wasn’t surprising when I interviewed the brilliant team of Lindsay Duncan and Alan Rickman in 2002 on the occasion of their transfer to Broadway of Davies’s smash West End production of Private Lives to hear both stars report people asking whether Coward’s comedy classic had somehow been rewritten?

In so doing, of course, he became a leading light, or star, largely by finding the human pulse and heartbeat to the play at hand. It wasn’t surprising when I interviewed the brilliant team of Lindsay Duncan and Alan Rickman in 2002 on the occasion of their transfer to Broadway of Davies’s smash West End production of Private Lives to hear both stars report people asking whether Coward’s comedy classic had somehow been rewritten?

The answer, of course, was no. Davies had simply encouraged his cast to play Coward’s comically envenomed comedy for its underlying pain as well as wit, the ache beneath the badinage: the result stamped a potentially shop-worn play afresh for a generation, just as Duncan and Rickman’s previous partnership in Davies’s defining premiere of Christopher Hampton’s Les Liaisons Dangereuses has yet to be equalled in any of the three revivals of that play I have seen in the years since.

Largely associated with the National Theatre, Davies in fact spread his talent far and wide, and I fondly recall his contribution to venues across the capital – from banner, headline-making ventures (Kevin Spacey and Eve Best in A Moon for the Misbegotten at the Old Vic, which went on to Broadway) to small jewels like Richard Nelson’s New England, an acerbic piece to which Davies brought the requisite polish and bite when it was premiered at the Barbican’s Pit in 1994. His Almeida Theatre revival of The Iceman Cometh, starring Kevin Spacey, transferred from Islington both to the Old Vic and then to Broadway, reminding playgoers along the way that five hours of Eugene O’Neill possess an innate energy that is there to be tapped, no matter how despondent the drunks that occupy centre stage.

Not for Davies time-wasters or diversionary games that took attention away from the work

Davies didn’t flinch in the face of stardom but met great actors head on, whether Spacey or Best or Julie Walters (who won an Olivier for that seminal All My Sons), or the mighty pairing of Judi Dench and Maggie Smith in a David Hare two-hander, The Breath of Life, whose title encapsulated Davies’s vitalising effect on the script. Grandes dames of the theatre didn't scare him; Davies seemed, however unobtrusively, always to have the upper hand.

He was at home across the repertoire. Lauded for a Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? that featured amongst its starry cast the actress (Clare Holman as Honey) who would become Davies’s second wife, the director did even better, arguably, by the world premiere at the Almeida of a blistering Edward Albee work, The Play about the Baby (1998), that Davies made funny and forbidding, as needed.

On the Russian front, his reclamations of Gorky (Philistines) and Bulgakov (the Olivier Award-winning The White Guard) brought to bear the full might of the National’s resources on two pieces of “total theatre” that did for the Russian canon what Davies’ work on The Shaughraun (marking an early example of the Olivier auditorium’s drum revolve) and, especially, The Silver Tassie did for the Irish canon (pictured above, photo by Catherine Ashmore). The wounding cry in Sean O’Casey play – “Dear God, this crippled form is still your child” – is seared on the memory to this day. Throughout it all, integrity and humanity were the constants, alongside a clear-eyed appraisal of his chosen profession that resisted sentimental guff. I vividly recall Davies once remarking how scarily easy it was on Broadway to be sacked; during another interview he spoke to me of a testy meeting that resulted in him pulling the tablecloth quite literally out from under his companion, who was a prominent New York producer.

Throughout it all, integrity and humanity were the constants, alongside a clear-eyed appraisal of his chosen profession that resisted sentimental guff. I vividly recall Davies once remarking how scarily easy it was on Broadway to be sacked; during another interview he spoke to me of a testy meeting that resulted in him pulling the tablecloth quite literally out from under his companion, who was a prominent New York producer.

Not for Davies time-wasters or diversionary games that took attention away from the work. Rather like a less rampaging Hickey in The Iceman Cometh, his was an ongoing report from the frontline of truth, and to reciprocate that intention, I will say but this: he was among the English-speaking theatre’s very best. That, for sure, is true.

TRIBUTES TO HOWARD DAVIES FROM FOUR DIRECTORS OF THE NATIONAL THEATRE

Rufus Norris: “Howard achieved an almost legendary status within the industry. His work – particularly on the American, Russian and Irish canons – was unparalleled. His reputation amongst actors, writers, directors and designers alike was beyond question, and has been for so long that his name has become a byword for quality and depth. His gaze and focus were unswerving, but his twinkling humour sat on the shoulder of his fierce intellect; either way, he always spoke his truth, and for a junior director that was both inspiring and frightening. His questions and opinion demanded the same rigour of others that he always applied himself, and his understated nod was the greatest compliment. He will be missed beyond measure.”

Nicholas Hytner: “Howard Davies was the director all actors wanted most to work with, and his productions were the ones I most wanted to see, always cracking with intellectual and emotional energy. He unlocked wild and contradictory passions in everything he did, and would describe a play not in terms of his concept, but of its humanity. He was the first person I asked to work with me when I became the National’s Director. I could not imagine being there without him, or doing the job without his friendship and support. He was the irreplaceable cornerstone. Among his countless outstanding productions, Bulgakov’s The White Guard in 2010 was as good as the theatre ever gets, an overwhelming experience. The National, the RSC and the theatre at large would be a shadow of themselves without everything he’s done for them; and so would all the actors, writers and directors whose lives were enriched by him.”

Trevor Nunn: “Ever since I first met Howard and employed him as an RSC assistant director, I have thought of him as an astonishingly brilliant young man. Through the time of him running the Donmar Warehouse, soon after the RSC opened it as a theatre, to his constant flow of legendary productions at the NT, he never ceased to amaze. For me, his NT production of All My Sons remains the greatest production of a 20th-century classic I have ever seen. The news of his death is incomprehensible.”

Richard Eyre: “He was a wonderful director, a wholly admirable man and a good friend.”

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

The Producers, Garrick Theatre review - Ve haf vays of making you laugh

You probably know what's coming, but it's such great fun!

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Not Your Superwoman, Bush Theatre review - powerful tribute to the plight and perseverance of Black women

Golda Rosheuvel and Letitia Wright excel in a super new play

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Cow | Deer, Royal Court review - paradox-rich account of non-human life

Experimental work about nature led by Katie Mitchell is both extraordinary and banal

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Deaf Republic, Royal Court review - beautiful images, shame about the words

Staging of Ukrainian-American Ilya Kaminsky’s anti-war poems is too meta-theatrical

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

Laura Benanti: Nobody Cares, Underbelly Boulevard Soho review - Tony winner makes charming, cheeky London debut

Broadway's acclaimed Cinderella, Louise, and Amalia reaches Soho for a welcome one-night stand

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

The Pitchfork Disney, King's Head Theatre review - blazing with dark energy

Thrilling revival of Philip Ridley’s cult classic confirms its legendary status

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Born with Teeth, Wyndham's Theatre review - electric sparring match between Shakespeare and Marlowe

Rival Elizabethan playwrights in an up-to-the-minute encounter

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Interview, Riverside Studios review - old media vs new in sparky scrap between generations

Robert Sean Leonard and Paten Hughes make worthy sparring partners

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Fat Ham, RSC, Stratford review - it's Hamlet Jim, but not as we know it

An entertaining, positive and contemporary blast!

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

Juniper Blood, Donmar Warehouse review - where ideas and ideals rule the roost

Mike Bartlett’s new state-of-the-agricultural-nation play is beautifully performed

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

The Gathered Leaves, Park Theatre review - dated script lifted by nuanced characterisation

The actors skilfully evoke the claustrophobia of family members trying to fake togetherness

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

As You Like It: A Radical Retelling, Edinburgh International Festival 2025 review - breathtakingly audacious, deeply shocking

A cunning ruse leaves audiences facing their own privilege and complicity in Cliff Cardinal's bold theatrical creation

Add comment