The American Dream: Pop to the Present, British Museum | reviews, news & interviews

The American Dream: Pop to the Present, British Museum

The American Dream: Pop to the Present, British Museum

Sixty years of print-making makes for a thrilling all-American portrait

Dream or nightmare? Bay of Pigs, assassinations, Vietnam, space race, Cold War, civil rights, AIDS, legalised abortions, same-sex marriage, ups, downs and inside outs. From JFK to The Donald in just under 60 years, as seen in 200 prints in all kinds of techniques and sizes by several score American artists (although, shush, a handful are – shock, horror – immigrants).

In The American Dream: Pop to the Present we are rushed through the isms from pop to agitprop, Conceptualism and Minimalism to figurative Expressionism and photorealism with a bow to geometric abstraction along the way: this is a wow of an exhibition. Seven years in the thinking, four years in the planning, and judicious purchasing and gifts mean some 70 percent is owned by the British Museum, which has an increasingly significant American collection including North American Indian art – serendipitously there is a choice showing of northwest Haida art concurrently on view there.

There are short and pithy films, interviews from Chuck Close to Julie Mehretu and Kiki Smith, and films of printmakers – cue Andy Warhol – making prints, with an elegant bow to the innovative printing firms and publishers that provided so much technical knowhow.

There are short and pithy films, interviews from Chuck Close to Julie Mehretu and Kiki Smith, and films of printmakers – cue Andy Warhol – making prints, with an elegant bow to the innovative printing firms and publishers that provided so much technical knowhow.

It is a can-do exhibition and what distinguishes it from so much of the period this side of the Atlantic is that clichéd but accurate view of American ambition, unembarrassed, unabashed, absolutely determined, thinking big. Here is something for everybody, the pains and pleasures of a diverse society expressed in images that celebrate the observed, and protest at inequalities. Prints reached a bigger audience, obviously, and various specialist and experimental print studios from Gemini GEL, Crown Point and Tamarind on the West Coast, to Andy Warhol’s screen prints emanating from his vast studio in New York, and Tatyana Grossman’s Universal Limited Art Editions to name but few.

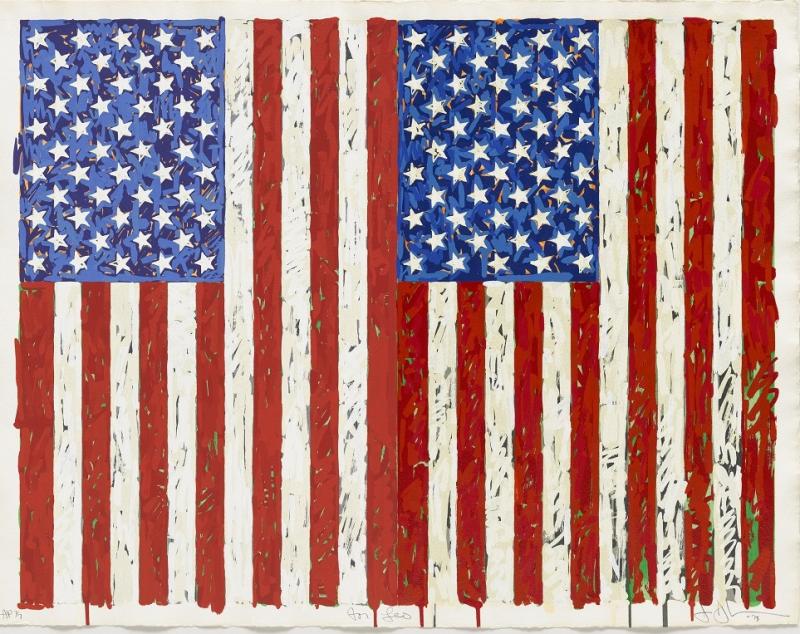

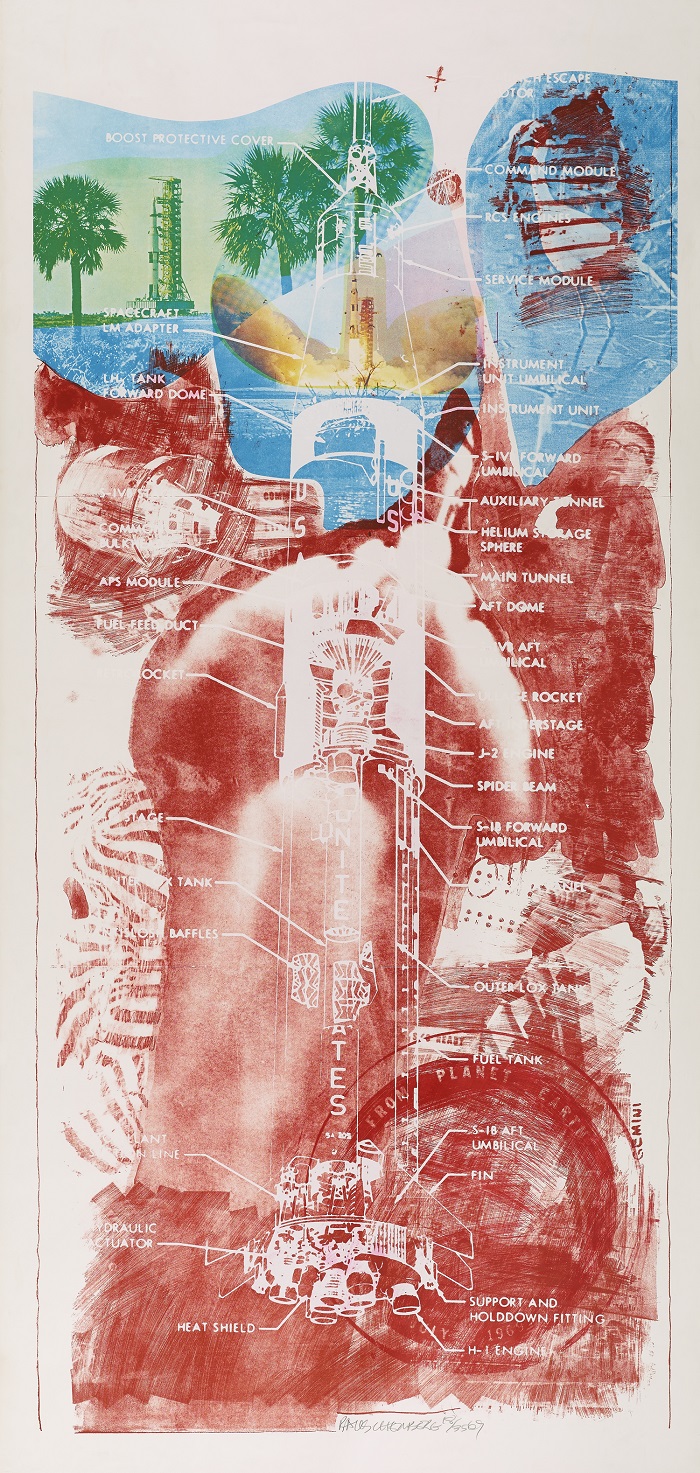

What is so striking and accessible about this multifarious display is the way artists embraced the quotidian, responded to events, subtly campaigned. The photorealists – Richard Estes, for example – turned sharp-focus photography on its head, showing with deadpan bravura ordinary shop fronts and signage, glittering with light from the plate glass of shop windows. Robert Rauschenberg used many sources including press photographs for montage mash-ups of political figures, space rockets and the like (pictured above right: Rauschenberg's Sky Garden from Stoned Moon, 1969. © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation/DACS). Jasper Johns, of course, with his superb sense of texture and colour took as his subject the sacred American icon, the flag (main image). There is an irony in turning it into a decorative object, almost a shocking sacrilege from an artist who could make of a beer can something dignified and important. Richard Serra makes monumental black prints, while Kara Walker creates telling images of the black experience (pictured above: no world from An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters, 2010. © Kara Walker). Chuck Close uses photography to make huge gridded portraits of friends and himself, imposing, impressive and curiously subversive. Ed Ruscha observes with an uncanny precision the disregarded: petrol stations, garages, rusting signs, dragging the everyday into the forefront of visual consciousness. The polemic anonymous campaigning Guerrilla girls use both text and image to indicate the disparity, through chilling statistics, of the representation of women in art. One hilarious print puts a guerrilla head on an Ingres Odalisque: Do women have to be Naked to Get into the Met. Museum?

Richard Serra makes monumental black prints, while Kara Walker creates telling images of the black experience (pictured above: no world from An Unpeopled Land in Uncharted Waters, 2010. © Kara Walker). Chuck Close uses photography to make huge gridded portraits of friends and himself, imposing, impressive and curiously subversive. Ed Ruscha observes with an uncanny precision the disregarded: petrol stations, garages, rusting signs, dragging the everyday into the forefront of visual consciousness. The polemic anonymous campaigning Guerrilla girls use both text and image to indicate the disparity, through chilling statistics, of the representation of women in art. One hilarious print puts a guerrilla head on an Ingres Odalisque: Do women have to be Naked to Get into the Met. Museum?

It seems every significant American artist of the period has tried his or her hand at print-making, but it also shows the cultural dominance of bi-coastal America.

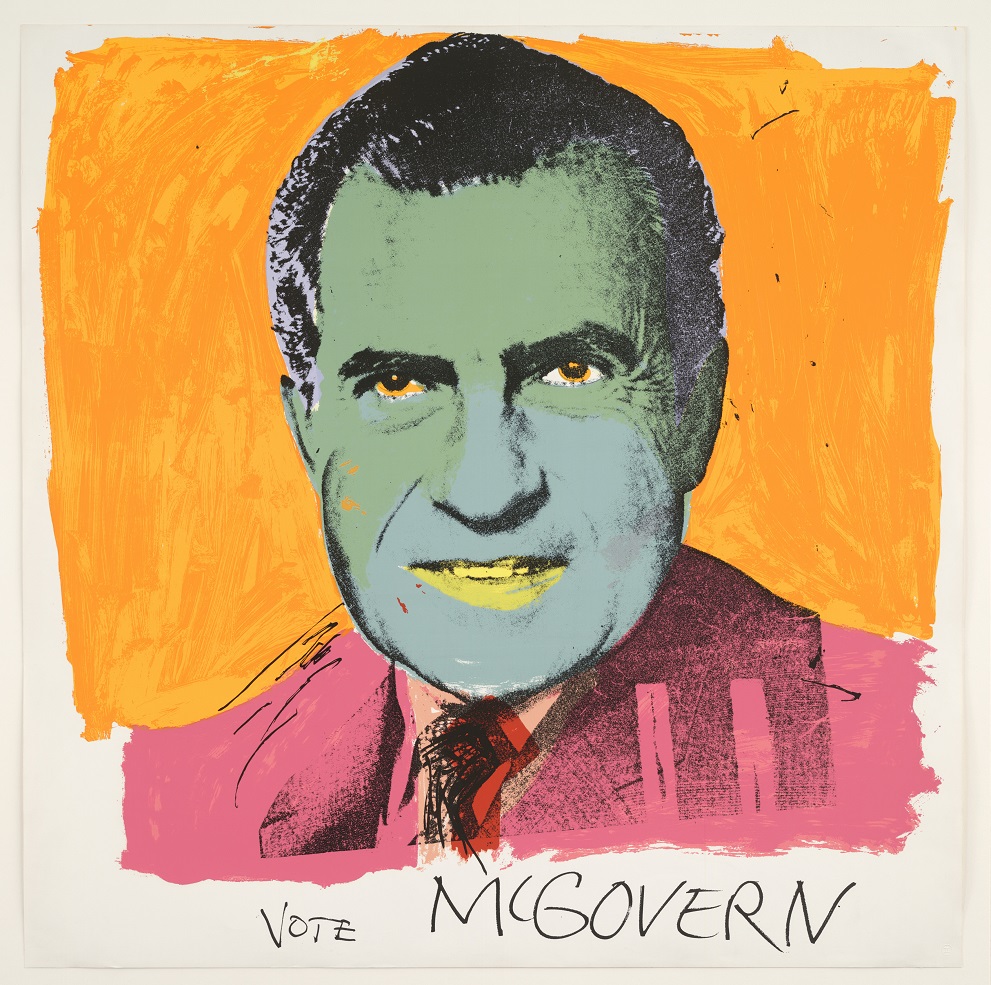

David Hockney is the honorary American, represented with his highly innovative Paper Pools (is the swimming pool an emblem of America?) done with Tyler Graphics: Ken Tyler, the Chicago-born son of immigrants, is a leading figure in technical innovation. More of Hockney’s quintessential Americana offers a neat supplement to Tate Britain’s retrospective. Pared-down Conceptualism/Minimalism includes Sol LeWitt, the master of the line in all its permutations. And with Warhol we have the gamut: Marilyn, Mao, Jackie, even the Campbell Soup Tin, not to mention that essential American invention of true horror, the Electric Chair. (Pictured above left: Warhol's Vote McGovern, 1972. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts).

David Hockney is the honorary American, represented with his highly innovative Paper Pools (is the swimming pool an emblem of America?) done with Tyler Graphics: Ken Tyler, the Chicago-born son of immigrants, is a leading figure in technical innovation. More of Hockney’s quintessential Americana offers a neat supplement to Tate Britain’s retrospective. Pared-down Conceptualism/Minimalism includes Sol LeWitt, the master of the line in all its permutations. And with Warhol we have the gamut: Marilyn, Mao, Jackie, even the Campbell Soup Tin, not to mention that essential American invention of true horror, the Electric Chair. (Pictured above left: Warhol's Vote McGovern, 1972. © The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts).

What is hypnotic about the anthology is its inclusiveness: touching portraits from Philip Pearlstein, stylised renderings of people from Alex Katz, Wayne Thiebaud’s delight in cafeteria food, and Vija Celmins’ superbly obsessive meditations on the ocean waves or the starry sky. A big range of Jim Dine moves from depictions of paintbrushes to bathrobes, to DIY tools and self-portraits. It is neatly divided into chapters, which means that although a big exhibition you can take your time – although more benches, please.

You can argue about who is in and who is out in this powerful, immensely enjoyable show which asks a lot of questions about whence and whither, not only for America, but also the idea of America. As the exhibition leaflet says, perhaps ironically, “Land of the free. Home of the brave”. But now what? Wherever America is heading, there will though be artists.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment