'What did you do?' Actors reveal their Shakespearean secrets | reviews, news & interviews

'What did you do?' Actors reveal their Shakespearean secrets

'What did you do?' Actors reveal their Shakespearean secrets

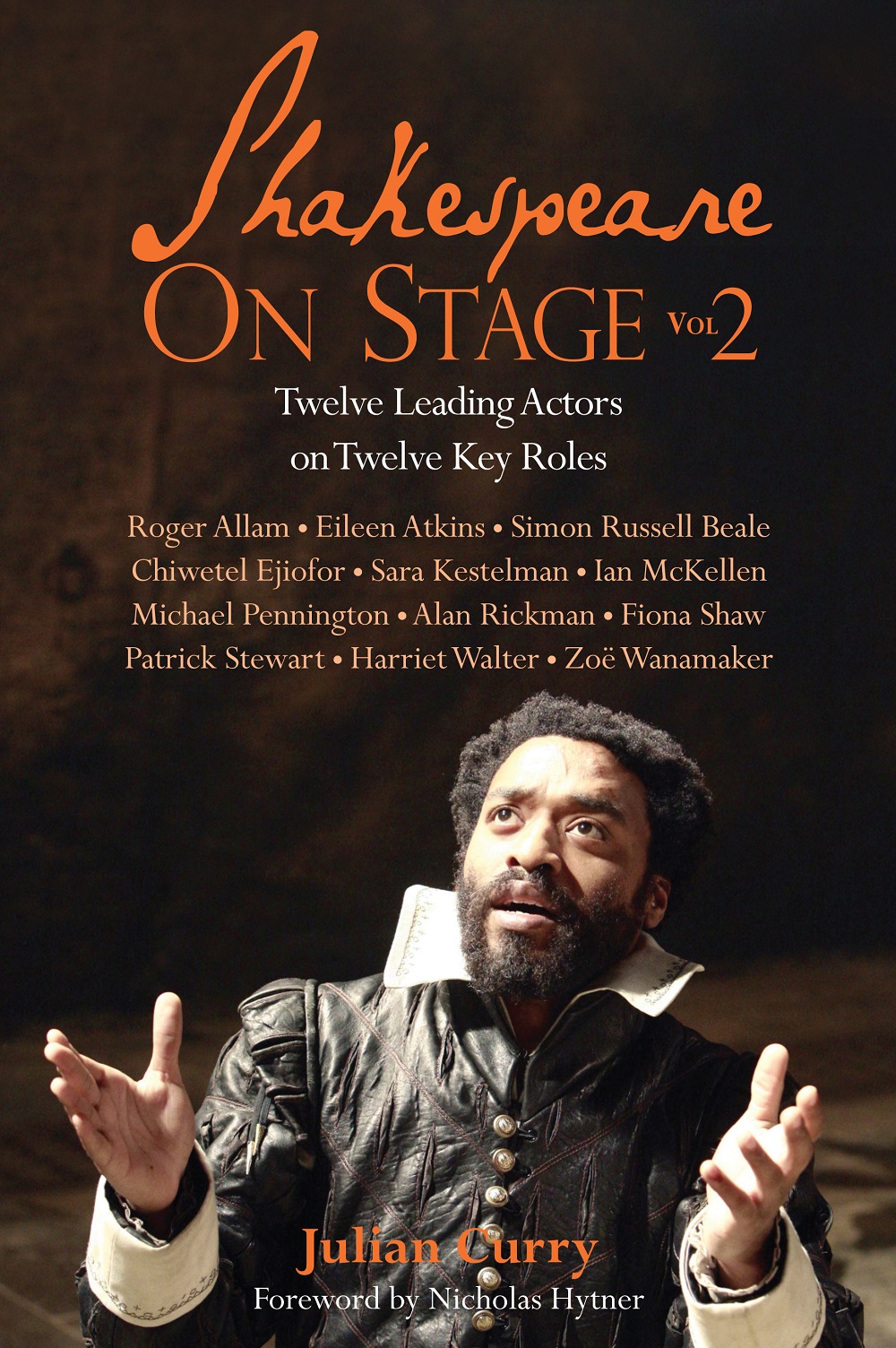

On the 401st anniversary of the Bard's death, actor-author Julian Curry introduces his new book of interviews, Shakespeare On Stage Vol 2

Much of the brilliance of Shakespeare lies in the openness, or ambiguity, of his texts. Whereas a novelist will often describe a character, an action or a scene in the most minute detail, Shakespeare knew that his scenarios would only be fully fleshed out when actors perform them. He was the first writer to create character out of language. Falstaff has an idiosyncratic way of speaking that is quite distinct from Juliet, as she does from Shylock, and he from Lady Macbeth.

George Bernard Shaw wrote long prefaces and elaborate stage directions; his texts are littered with instructions to actors and directors as to how his plays should be done. This can be helpful, but as often as not it’s limiting, even annoying. Shakespeare, conversely, wrote hardly any stage directions. The best known is "Exit, pursued by a bear" in The Winter’s Tale – which incidentally is far from proscriptive: is some unfortunate actor bundled into a bear costume? Or is the bear surreal, an effect of sound and lighting? Directors have carte blanche. The only solution rarely adopted is to put a live bear on stage. On occasion Shakespeare does give a precise indication of stage business. In the courtroom scene of The Merchant of Venice, Gratiano says: “Not on thy sole but on thy soul, harsh Jew, / Thou mak’st thy knife keen” [4.1]. Then the actor playing Shylock understands that he should take out his knife and sharpen it on the sole of his shoe. Other stage directions take the form of implicit but less precise suggestions. When Hamlet says to Osric, “Put your bonnet to his right use; ’tis for the head” [5.2], the actor playing Osric knows one thing for sure: his hat is not on his head. How else he is using it is up to him.

There are times when the actor may decide to do the opposite of what the text seems to indicate. For instance, when King Lear exits saying to Goneril and Regan, “You think I’ll weep? No, I’ll not weep... this heart / Shall break into a hundred thousand flaws / Or ere I’ll weep” [2.4], the suggestion appears to be that the actor will remain dry-eyed. Ian McKellen immediately burst into convulsive sobs. I found this very moving. Shakespeare doesn’t tell his actors how to play their parts; he gives hints but leaves the decisions up to them. My interest in writing Shakespeare On Stage: Volume 2, and the companion volume that preceded it, is the myriad options available to performers of Shakespeare’s texts, and the choices they make. Theatre is written on the wind. Even the most brilliant performances exist only in the moment, and will endure nowhere but in the memories of those present. Actors are notoriously reluctant to define and discuss how they act, but luckily they are often willing to talk about their past performances.

As with the earlier volume, my guiding principle was to approach excellent actors who had played leading roles in memorable Shakespearean productions, and to ask them if they’d be willing to reveal if not how they acted, at least what they did. I also wanted to know how the show was set, what they wore, and what went on around them. Having been lifelong in the business, many of my intended targets were friends who were easily accessible, and most generous with their time.

As with the earlier volume, my guiding principle was to approach excellent actors who had played leading roles in memorable Shakespearean productions, and to ask them if they’d be willing to reveal if not how they acted, at least what they did. I also wanted to know how the show was set, what they wore, and what went on around them. Having been lifelong in the business, many of my intended targets were friends who were easily accessible, and most generous with their time.

Preparing for each encounter was a labour of love. Of necessity it involved a thorough refresher course, going back to the plays and spending long hours with nose in text. I also read critical studies and pestered archivists for back copies of reviews. I was determined to approach the interviews as well briefed as possible, in order to frame productive questions. At times it felt like the work of a barrister. The difference is that whereas a barrister’s questions are designed to steer the witness towards a desired answer, mine were simply intended to get juices flowing and tongues wagging. I concentrated on mechanics rather than theory. As far possible I made the question “What did you do?” rather than “How did you do it?”

The resulting book is an account of 12 performances, by the actors who gave them. Each interview focuses on a single performance, and the production in which it featured, spanning 50 years, from Eileen Atkins’s Viola in 1961 to Patrick Stewart’s Shylock in 2011. What they have in common is a uniquely personal account of a creative process. I was delighted by the frequent departures from lazy assumption. For instance, Sara Kestelman describes A Midsummer Night’s Dream set in an immaculate white box utterly devoid of vegetation, or tiny fairies with wings. Simon Russell Beale, who looks anything but lean and hungry, was triumphantly cast as Cassius. Patrick Stewart’s Shylock ruled over a business empire set in Las Vegas. Ian McKellen repeatedly questions the assumption that King Lear goes mad, just as Alan Rickman finds the adjective “melancholy” inadequate to describe Jaques. But there the similarities end. I’m not aware of any other continuities or recurring themes. On the contrary, each one quite naturally occupies its own territory, and I’m happy with that. It also seems that, as a by-product, the actors have in fact revealed a great deal about themselves and their own working methods. As such, I hope the reader will enjoy the range and diversity of responses, and that it will be of interest to other actors, students and theatregoers alike.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment