Jules Dalou, Edouard Lantéri, Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, Charles-François Daubigny, Alphonse Legros, Giuseppe de Nittis? Perhaps not household-name Impressionists, but the subtitle of Tate Britain's exhibition, French Artists in Exile 1870-1904, makes things clearer: this is really an examination of cross-channel conversations occasioned by the drastic military and political crisis in France in 1870-1871 – the Franco-Prussian war, followed by the Commune.

Not only did some 230,000 or more combatants and civilians die, but many a familiar landmark was pulverised as central Paris was profoundly damaged. Fearful of conscription, artists like Monet came to London, living in relatively reduced circumstances, their livelihoods threatened as the French art market found itself in serious difficulties. Then, as now, refugees came for political and economic reasons, leaving devastation behind, and hoping for new opportunity.

The cross-channel journeys of the artists led to unexpected consequences. In the penultimate gallery there is a hypnotically beautiful coup de théâtre, late Impressionism at its finest, with six views by Monet of Westminster from 1904, never seen together before in London, and created on trips made some 30 years after his initial temporary exile. This is the largest group to be shown in Europe for nearly half a century, and sensational they are, as are two of his views of Charing Cross. He was transported and inspired, he said, by the changing colours in the fog and rain of London: coal fires were a health hazard but produced beautiful skyborne effects. These are canvases of transcendent beauty: the buildings of Westminster punctuate the urban atmosphere. Monet is that rare creature whose art in the 21st century looks ever more radical and ever more beautiful. (Pictured below: Claude Monet, Houses of Parliament, Sunlight Effect, 1903, Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York)  The final gallery gives us the coming vibrancy of the modern world. The brilliant coda there is a selection of Thames-scapes, 1906-7, by André Derain, heavily patterned like an imaginative jigsaw puzzle, with stridently brilliant, almost savage, colour. Derain had seen an exhibition of Monet’s views of the Thames at Durand-Ruel’s Paris gallery in 1904, but his views – divisionist, expressionistic – were a striking contrast as art idioms moved on in a push-me, pull-you fashion. His dealer Vollard wanted Dérain to emulate Monet’s success with his new take on views of the Thames.

The final gallery gives us the coming vibrancy of the modern world. The brilliant coda there is a selection of Thames-scapes, 1906-7, by André Derain, heavily patterned like an imaginative jigsaw puzzle, with stridently brilliant, almost savage, colour. Derain had seen an exhibition of Monet’s views of the Thames at Durand-Ruel’s Paris gallery in 1904, but his views – divisionist, expressionistic – were a striking contrast as art idioms moved on in a push-me, pull-you fashion. His dealer Vollard wanted Dérain to emulate Monet’s success with his new take on views of the Thames.

Welcome as the wondrous Monets are, Impressionism is a marketing come-on for this intriguing anthology. The story that Tate reveals is complex, with much presented as visual history: sketchbooks, documentary photographs of the destruction of Paris, beautifully and horrifically detailed. The art varies from the gracefully academic to the almost stodgy – dare one say, boring? – technically accomplished but curiously empty sculptures by Jules Dalou and Jean Baptiste Capeaux.

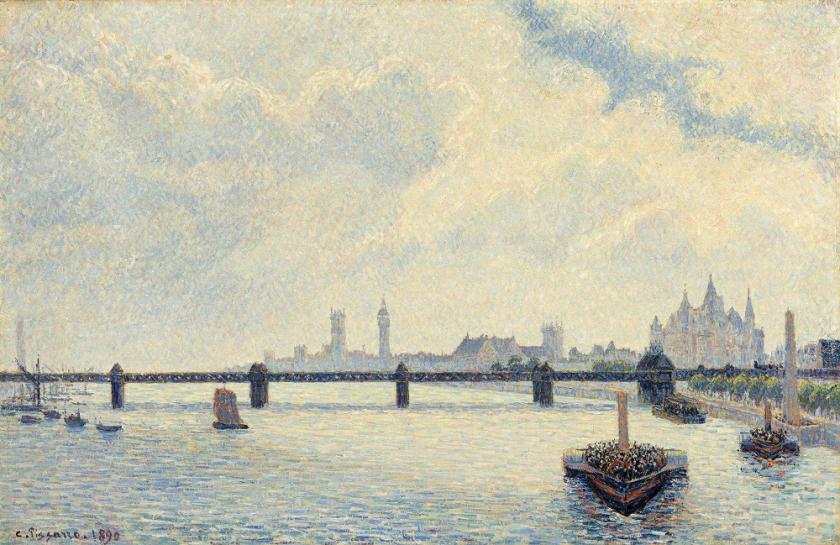

Each artist has a different story. James (Jean-Jacques) Tissot (1836-1902) had defended Paris in the Franco-Prussian war, become involved with the Commune and moved to London, perhaps to escape political consequences, and also possibly for more success; indeed he exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy. Tissot was a hallucinatory painter (and a skilled watercolourist and printmaker) whose techniques in oil on canvas have much more in common with the Pre-Raphaelites and High Victorians like Lord Leighton, without the moralising overtones. He was a mesmerising social reporter, and moved back to Paris after the death of his beloved mistress Kathleen Newton (pictured below: James Tissot, The Ball on Shipboard, c.1874).  Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), the sage and wise paternal figure to so many of the Impressionists, is here with his wonderfully evocative paintings of south London suburbs, of Kew, and cricket on the lawn: they look so tightly knit compared to the resplendently sensual sweeps of colour deployed by Monet in his London views (main picture: Camille Pissarro, Charing Cross Bridge, 1890). The Anglo-French Albert Sisley (1839-1899) is here too, his home and prospects destroyed by the Prussians.

Camille Pissarro (1830-1903), the sage and wise paternal figure to so many of the Impressionists, is here with his wonderfully evocative paintings of south London suburbs, of Kew, and cricket on the lawn: they look so tightly knit compared to the resplendently sensual sweeps of colour deployed by Monet in his London views (main picture: Camille Pissarro, Charing Cross Bridge, 1890). The Anglo-French Albert Sisley (1839-1899) is here too, his home and prospects destroyed by the Prussians.

This is an exhibition which shows by example the enriching value of welcoming refugees, not to mention visitors from elsewhere, both political and economic. In an age when there were no passport or visa restrictions, some artists had settled earlier. The highly skilled painter and printmaker Alphonse Legros became a Slade professor, and embedded himself in English cultural life. The sculptors Lantéri and Dalou – the latter returned to Paris with great success in 1879 – were also teachers, and influenced the curricula in the London art schools, by virtue of their uncanny skills at modelling. Carpeaux came and went for economic advantage, and also hoping for patronage from the royals of the Second Empire, deposed and in exile in England.

The array of relatively unfamiliar artists is intriguing and informative, giving a rounded view of the period. The high academic competence of these currently relatively disregarded artists can – alas – produce an art lacking in vitality. But this art points out the astonishing nature of the Impressionist experiments, reactions to the prevailing meticulous nature of both painting and sculpture in the landscape of conventional academia. And with a soupçon of Rodin, introduced to an English audience by his French compatriots, we see how even academic correctness could be transcended.

- Impressionists in London, French Artists in Exile (1870-1904) at Tate Britain until 22 April 2018

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment