As the ice hardened in the Cold War of the mid-1950s, and the USSR mocked the USA for both its supposed barbarism and racial segregation, the representative from Harlem, Adam Clayton Powell Jr, had a bright idea. Instead of competing in the cultural heats of the Cold War on Soviet strengths of classical music and ballet, why not bring the world that quintessentially, originally American art form, jazz? With the added benefit that most jazz ensembles were racially mixed, to dispel the Soviet claims about segregation.

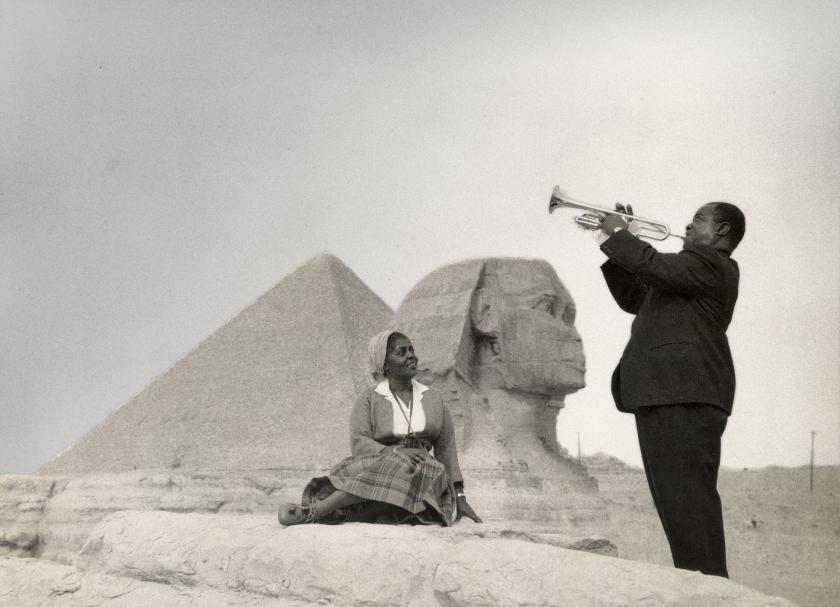

Powell’s wife, Hazel Scott, was a jazz singer, and he was close friends with stellar trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie, who was chosen as the first band leader to represent American values. Over the next eight years, most of the cleaner-living stars of 1950s and 1960s jazz took a turn: Armstrong, Ellington, Brubeck and Benny Goodman. They travelled anywhere there was doubt about the Cold War affiliations of the local population, which mainly meant India, Africa and the Middle East.

The reception the ambassadors received spanned ecstatic to transformational. In Athens in 1956 Dizzy Gillespie (photographed below, with his band in Turkey) charmed a student protest that had, that morning, been lobbing rocks at the US Embassy. Dave Brubeck’s homage to Chopin, “Dziękuję” (Thank You), left Polish audiences speechlessly overcome. In Moscow, Benny Goodman’s band took part in a clandestine jam with Russian musicians at the university that would, had the KGB found out, have prompted their abrupt withdrawal to some distant, frost-bound labour camp.

Perhaps most extraordinary, Louis Armstrong’s band inspired a 24-hour ceasefire during the civil war in the Democratic Republic of Congo so both sides could enjoy the gig. (The USSR accused the US, with some justification, of using Armstrong as a diversionary tactic from their collusion in the deposition of DRC prime minister Patrice Lumumba.) Whether these tours had any substantial political effect is less certain. Penny M. von Eschen, author of a study of Armstrong’s tours, cast doubt on the idea, suggesting that the hard detail of foreign policy was ultimately more influential.

Musically, claims were made that these tours were a two-way process of education and influence. Darius Brubeck, the pianist’s son, who accompanied his father on some of his tours, explained that "Blue Rondo a la Turk" was inspired by the street musicians of Izmir. Ellington’s album The Afro-Eurasian Eclipse is infused, to some extent, with the sounds of India and the near east he heard on a tour cut short by JFK’s assassination. Otherwise, the tours, although long and physically gruelling, seem to have been flattering rather than inspiring for the musicians involved.

Musically, claims were made that these tours were a two-way process of education and influence. Darius Brubeck, the pianist’s son, who accompanied his father on some of his tours, explained that "Blue Rondo a la Turk" was inspired by the street musicians of Izmir. Ellington’s album The Afro-Eurasian Eclipse is infused, to some extent, with the sounds of India and the near east he heard on a tour cut short by JFK’s assassination. Otherwise, the tours, although long and physically gruelling, seem to have been flattering rather than inspiring for the musicians involved.

“Ambassadors” gives a misleading impression of the musicians’ political docility and obedience. The period of the ambassadors’ programme coincides with both jazz musicians’ peak cultural status and influence and the incipient stages of the civil rights movement. Many of these performers knew they could make a difference, and did so. Though Armstrong had in some respects been used as a smokescreen for the government’s involvement in regime change in DRC, he was politically aware, and willing to use his influence. He had withdrawn from negotiations about a 1957 tour after the federal government refused to intervene to ensure school integration in Little Rock, Arkansas, declaring, “The way they are treating my people in the south, the government can go to hell.” Two weeks later, Eisenhower sent the National Guard to Little Rock, and Armstrong went on a tour of South America. A campaign against the US government’s involvement in DRC, meanwhile, was led by a younger generation of jazz musicians, including Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln.

Relations improved under JFK, but in the early years there was little love lost between the jazzers and the Eisenhower administration, who began querying both the costs and musical quality - in Gillespie’s case, this was very modern jazz - of the tours. The feeling was mutual. “The powers that be were basically racist people, especially in the south,” recalled Gillespie’s drummer, Charlie Persip.

Several interviewees attempted to construct allegories about jazz and democracy, suggesting that the freedom to improvise within a regulated framework made jazz both figuratively and practically the perfect advocate for democracy. Perhaps. A different, but similar, argument could be made about the democratic virtues of stars from any branch of American popular culture. While it’s true that jazz was popular in the Eastern Bloc partly for its associations with America, the ecstatic throngs who greeted each one of these tours in the footage shown here looked as though they were enjoying the music more for its exuberant brilliance than its allegorical heft.

The ambassadors programme gradually faded after the assassination of JFK. Even if it hadn’t, by the end of that decade rock bands were touring prolifically, and promoting American values, with no need of help from the US Information Agency. Truth be told, the insight offered by the ambassadors scheme into jazz as music is limited, but for a snapshot across critical areas of American domestic and foreign policy, during a period of radical change (as regards civil rights, at least) it was both fascinating and well told.

In 1958 the New Yorker ran a cartoon depicting officials talking round a table. One said: “This is a diplomatic mission of the utmost delicacy. The question is, who’s the best man for it - John Foster Dulles [secretary of state] or Satchmo?” Try re-phrasing with a musician of today and you’ll see how extraordinary the position of these ambassadors was, for a music only a few decades old. Kanye? Bono? Anyone?

Add comment