Pianist Christopher Glynn on Schubert in English: 'this new translation never walks on stilts' | reviews, news & interviews

Pianist Christopher Glynn on Schubert in English: 'this new translation never walks on stilts'

Pianist Christopher Glynn on Schubert in English: 'this new translation never walks on stilts'

On working with Roderick Williams and Jeremy Sams on 'Winter Journey'

The idea for a new translation of Schubert's Winterreise came from an old recording. Harry Plunket Greene was nearly 70 (and nearly voiceless) when he entered the studio in 1934 and sang "Der Leiermann," the final song of the cycle, in English (as "The Hurdy-Gurdy Man") into a closely-placed microphone.

There’s a disarming directness to this singing – and it seems inextricably bound up with that fact that Plunket Greene chooses to sing in his native language. Like many singers of his pre-war generation, he often sang Lieder in translation, perhaps because communicating in the audience’s own language was thought to be as important as fidelity (or another kind of fidelity) to the composer’s original intentions.

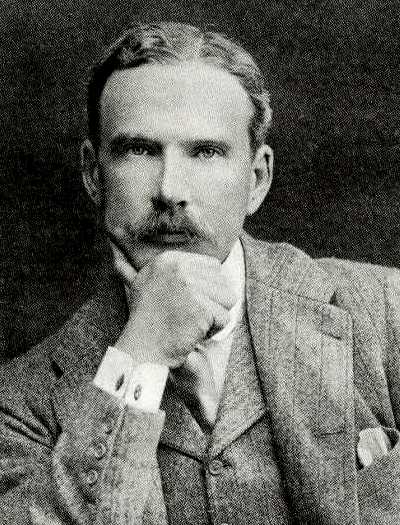

For later generations of singers, no doubt influenced by the legacy of German-speaking artists like Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, it became an article of faith that Lieder should always be sung in the original language. But returning again and again to Plunket Greene’s "Leiermann," (the Irish baritone pictured left in younger days) I wondered whether a translation could help unlock the cycle for new listeners. Because even in the classical music world, song recitals are rarer than they might be – a niche within a niche – and I know from my own experience as a festival director that only a subset of the audience can be persuaded to listen to a whole evening of songs in a foreign language. What would it be like to hear Winterreise sung in modern English? Could it help new listeners (and singers) get to know Schubert’s traveller, just as Plunket Greene did?

For later generations of singers, no doubt influenced by the legacy of German-speaking artists like Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, it became an article of faith that Lieder should always be sung in the original language. But returning again and again to Plunket Greene’s "Leiermann," (the Irish baritone pictured left in younger days) I wondered whether a translation could help unlock the cycle for new listeners. Because even in the classical music world, song recitals are rarer than they might be – a niche within a niche – and I know from my own experience as a festival director that only a subset of the audience can be persuaded to listen to a whole evening of songs in a foreign language. What would it be like to hear Winterreise sung in modern English? Could it help new listeners (and singers) get to know Schubert’s traveller, just as Plunket Greene did?

After a few fumbling attempts at translating the songs myself, I soon gave up and asked Jeremy Sams, wordsmith and polymath extraordinaire, if he’d take on the challenge. As the son of the great Lieder expert, Eric Sams, Jeremy has these songs in his blood and knows them intimately, but also shares my enthusiasm for bringing them to a wider audience. As the first drafts began to arrive over email - wonderfully lyrical and direct – it was clear that Jeremy’s winter traveller would speak the language of Everyman, echoing the "naturalness, truth and simplicity" to which Wilhelm Müller thought all poetry should aspire. My favourite thing about this new translation is that it never walks on stilts.

It’s true, though, that translation always involves elements of compromise. Jeremy himself describes the process as ‘a devilish game of four dimensional chess’ and no-one should underestimate how difficult it is. But isn’t there perhaps a compromise when songs are heard in a foreign language too? We tend to be faced with a choice between giving half our attention to the translation in the programme (thereby missing much of the expression that comes through a singer’s face and body language) or engaging fully with the performance but perhaps missing some of its meaning. And even those who understand the German words will never have the same emotional response to them as they do to their mother tongue.

After one such performance in Hull, Roderick had the idea of taking Winter Journey on nationwide schools tour – exactly the kind of project I’d hoped the new translation would enable, and one to which I readily agreed. So we’ve set aside three weeks next year to perform it to (and with) secondary school students all over the country – a sort of Schubert roadshow. We want them to feel this is their music - that Schubert belongs to them every bit as much as Ed Sheeran does. Another project in the pipeline will involve imagining what happens after that strange meeting in "Der Leiermann" between Schubert’s traveller and the hurdy-gurdy-playing beggar.

I’ve come to think of song translation as something like a film adaptation of a classic novel. Not a replacement for the original but a homage to it, faithful to the spirit if not always the letter, and with the possibility of reaching a broader public. It can be a stepping-stone to the original, or just enjoyed in its own right. Perhaps all the best translations are about the joy of discovery?

Not everyone will like it. For some, quite understandably, the original marriage of words and music is sacrosanct; whilst for others, not knowing exactly what is happening just adds to the mystery, or allows them to imagine their own stories into the music. Nothing wrong with that. But perhaps there is also room for a vernacular Winter Journey that offers the chance to experience meaning and music together, with something of the same immediacy that the composer surely intended when he sat down at the piano in 1827 and first shared the cycle with a group of his closest friends. Song is, after all, the conjunction of sound and sense; so Jeremy, Roddy and I hope that, for at least some listeners, Winterreise will be found in translation.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Two-Piano Gala, Kings Place review - shining constellations

London Piano Festival curators and illustrious friends entertain and enlighten

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Echo Vocal Ensemble, Latto, Union Chapel review - eclectic choral programme garlanded with dance

Beautiful singing at the heart of an imaginative and stylistically varied concert

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Scott, Irish Baroque Orchestra, Whelan, RIAM, Dublin review - towards a Mozart masterpiece

Characteristic joy and enlightenment from this team, but a valveless horn brings problems

Add comment