This final episode of BBC Four's Looking for Rembrandt, exploring the life and work of the Netherlands’ greatest painter, was a mini-masterpiece in itself. We rejoined the story in the mid-1650s, when Rembrandt found that his days of popular acclaim and patronage by heads of state and the nobility were behind him. Instead, he had discovered to his horror that “my pupils are more popular than me and I’m fodder for the gossips.”

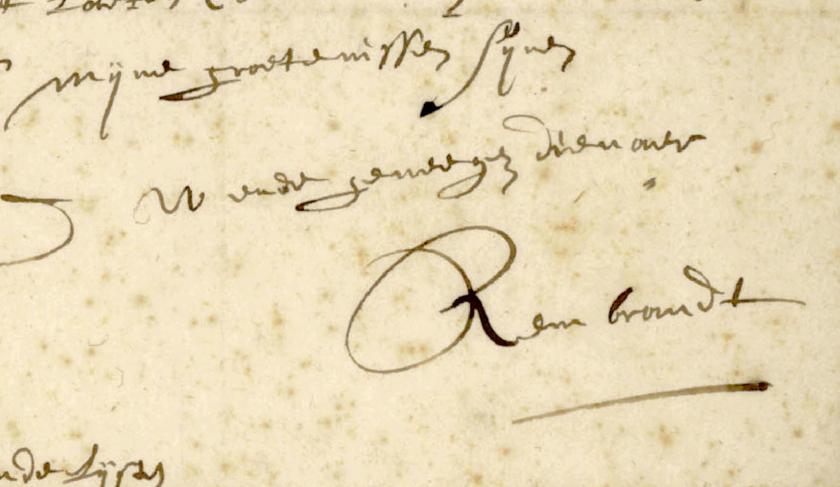

It was an inspired move to hire Toby Jones as the voice of the artist. Resisting any urge towards thespian grandstanding, Jones conveyed the varied facets of the painter’s personality with a range of subtle inflections and shifts of tone. He could sound wry and witty, dejected and downtrodden, cynical and resentful, and sometimes devious and cunning. Since Rembrandt left virtually nothing in the way of letters or diaries, all credit to writer and director Tim Niel, who has shown great ingenuity in constructing this persuasive first-person narrative (pictured below, Rijksmuseum director Taco Dibbits with The Night Watch).

Skilful, too, was the way the artist’s life and work were knitted together, each throwing light on the other. Though he was growing old and had fallen out of fashion, Rembrandt was continuing to make huge artistic breakthroughs, as a painting such as The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Deijman revealed (a squad of critics and museum curators was on hand to unpick the many strands of Rembrandt’s genius). But much of his time was spent fighting off creditors and struggling to eke out a living – “I’m just a painter, desperate for the thousand guilders that I’ll get when this is finished.”

Skilful, too, was the way the artist’s life and work were knitted together, each throwing light on the other. Though he was growing old and had fallen out of fashion, Rembrandt was continuing to make huge artistic breakthroughs, as a painting such as The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Deijman revealed (a squad of critics and museum curators was on hand to unpick the many strands of Rembrandt’s genius). But much of his time was spent fighting off creditors and struggling to eke out a living – “I’m just a painter, desperate for the thousand guilders that I’ll get when this is finished.”

He was by no means entirely scrupulous. When he held a sale of his possessions to raise desperately-needed cash, he hired rooms at an inn for the purpose, but never paid for them. His transfer of the deeds of his house to his son Titus to prevent it being sold to cover his debts was, essentially, fraud. The ploy by Titus and Rembrandt’s partner Hendrickje to create a business and hire Rembrandt as a salaried employee would have earned the admiration of many an expert tax lawyer.

The end of his life was a litany of tragedies, including the deaths of his son and partner. If it was any consolation to him, his work grew ever more insightful and expressive. The Jewish Bride seems to enshrine his love for Hendrickje, while Simeon in the Temple can be read as a memorial to his son and baby grandchild. Rembrandt was buried in a rented grave at a cost of 15 guilders, but his reputation looms ever larger.

Add comment