Rutger Bregman: Humankind, a Hopeful History review – nice guys finish first | reviews, news & interviews

Rutger Bregman: Humankind, a Hopeful History review – nice guys finish first

Rutger Bregman: Humankind, a Hopeful History review – nice guys finish first

Human nature shines in this spirited whirl through history and science

In retrospect, we will surely see that British battles over the Covid-19 lockdown harboured within them a bitter but half-hidden war of ideas. On one side, the behavioural scientists who first guided policy seemed to depend on a model of human beings as (in Rutger Bregman’s words) “selfish, aggressive and quick to panic”. Early signs, such as the spate of hoarding, served to confirm their stance.

Bregman is a young Dutch writer and researcher whose first book, Utopia for Realists, advocated a Universal Basic Income among other proposals for a fairer, happier society. Here in Britain, we don’t yet enjoy Utopia but, thanks to the pandemic, we do now have UBI in the shape of income support for millions of workers. Under the pressure of events, the impossible tends to become possible. Humankind, however, recommends not so much an outlandish swerve of policy as a mental reboot; not the creation of new realities but a recognition of those that actually exist. For Bregman, politicians, scientists, philosophers and clerics have drummed into us the belief in an innate human selfishness that results in perennial conflict, war, inequality and injustice. Even if we don’t adhere to St Augustine’s doctrine of “original sin”, mighty paradigms from the “selfish gene” theory to the political thought of giants such as Hobbes and Machiavelli, and many schools of psychology and economics, promote a “grim view of humanity” as monsters of egotism, driven by want, greed and fear. Our surface shows of kindness and civility only act to mask the “calculating robot” underneath.

In a book that thinks big, aims high but stays cheerful – in a rather Dutch way, forthright, robust and pragmatic – Bregman seeks to pierce this armour-plated cynicism. As he moves between history, philosophy, anthropology and psychology with no respect for boundaries, or for reputations, he flays the sacred cows of the born-bad – or the evolved-to-be-mean – brigade. Not only do notions such as the “veneer theory" – that civilised order is but a thin crust atop a seething lava of aggression and cruelty – darken the light in which we see our fellow-beings. They deliver the opposite of a placebo effect: a nocebo effect that worsens social outcomes. After all, “you get what you expect to get”. This kind of pessimism becomes “a self-fulfilling prophecy”. It primes economies and societies to breed exactly the sort of suspicious, competitive and ultra-individualistic beings its dismal outline of humanity mandates.

In a book that thinks big, aims high but stays cheerful – in a rather Dutch way, forthright, robust and pragmatic – Bregman seeks to pierce this armour-plated cynicism. As he moves between history, philosophy, anthropology and psychology with no respect for boundaries, or for reputations, he flays the sacred cows of the born-bad – or the evolved-to-be-mean – brigade. Not only do notions such as the “veneer theory" – that civilised order is but a thin crust atop a seething lava of aggression and cruelty – darken the light in which we see our fellow-beings. They deliver the opposite of a placebo effect: a nocebo effect that worsens social outcomes. After all, “you get what you expect to get”. This kind of pessimism becomes “a self-fulfilling prophecy”. It primes economies and societies to breed exactly the sort of suspicious, competitive and ultra-individualistic beings its dismal outline of humanity mandates.

Bregman sprints at a breakneck pace around history and science in his efforts to show the intrinsically friendly and co-operative traits of “Homo puppy” – the naked ape that evolved so successfully, in this light, because of its open, trusting and helpful nature. For Bregman, the ascent of our species bears witness to "the survival of the friendliest". And crisis only fortifies our virtues. The London Blitz brought not the savage social breakdown Whitehall expected but its caring, sharing antithesis – just the same happened in bombed German cities. When a group of boys were really shipwrecked on a Pacific Island they created not William Golding’s Lord of the Flies – a special bugbear for Bregman, unfairly to this reader’s mind – but a peaceable, practical commune. The people of Easter Island – a favourite case among thinkers who espouse “the fatalistic rhetoric of collapse” – fell into catastrophe not because of inherent rivalry and aggression but thanks to the disasters imported from abroad on ships. Astonishing evidence from many battlefields indicates that a large proportion of soldiers never use their weapons in anger: in one study, over 80 per cent of guns went unfired. For Bregman, we evolved to benefit from co-operation and “Humans are simply not wired for war”.

At this book’s core lies a sustained debunking of some of the key studies that, through the post-war decades, helped to solidify the belief in our species as a “killer ape”, forever prone to violence, persecution and tribal conflicts in our everyday behaviour. Bregman is far from the first sceptic to unpick and ridicule these landmark projects in social psychology, such as Stanley Milgram’s notorious alleged proof that most people will become torturers when instructed by authority, or the Stanford Prison Experiment which supposedly showed our propensity for group sadism. He castigates them as flawed fictions, “staged farces”, or even plain “hoaxes”. In the same era, investigators went into the jungle to report, misleadingly, on exactly the sort of aggression and xenophobia that they wanted to find among isolated tribes. Not much of this indictment is new. But Bregman handily, and enjoyably, draws up a damning charge-sheet against the Wicked Humans hypothesis and its propagators. Crucially, he shows that such experiments won fame just as a full understanding of the Holocaust and other genocides took root everywhere. In the reputedly carefree 1960s, the nightmares of the century finally hit home, and the verdict on humankind turned sour.

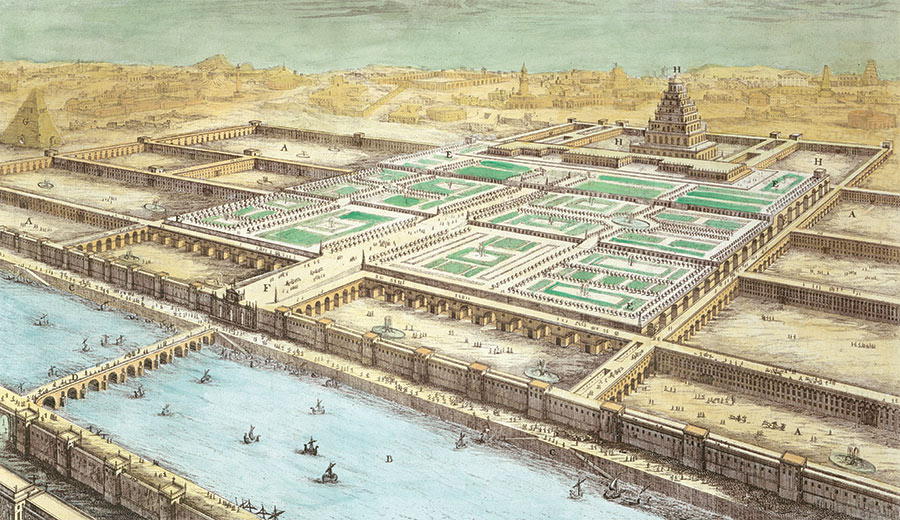

Bregman, of course, still has to account for the florid atrocities of history, and for its slow-burn miseries of injustice and oppression. Like many authors before him, going back to the anarchists of the 19th century, he posits a golden age of nomadic equality among our hunter-gatherer forebears. In this perspective, permanent settlements, agriculture and city life have ruined the human neighbourhood. Populations boomed; scarcity replaced abundance; leisure gave way to toil. Spreading out from the “fertile crescent” where cities such as ancient Babylon (pictured top) grew, new types of ruler, priest and indeed god inflicted “the curse of civilisation” on our species of once-happy wanderers. In this reading, the heirs of bullying priest-kings are those politicians and plutocrats who exhibit “acquired sociopathy” and extreme selfishness to a freakish degree – but whose power lets them mould much of society in their abnormal image. A fairy-story this may be, but Bregman tells it winningly well. Besides, the patchy evidence from distant prehistory means that rival narratives have no firmer foundation than his.

Bregman, of course, still has to account for the florid atrocities of history, and for its slow-burn miseries of injustice and oppression. Like many authors before him, going back to the anarchists of the 19th century, he posits a golden age of nomadic equality among our hunter-gatherer forebears. In this perspective, permanent settlements, agriculture and city life have ruined the human neighbourhood. Populations boomed; scarcity replaced abundance; leisure gave way to toil. Spreading out from the “fertile crescent” where cities such as ancient Babylon (pictured top) grew, new types of ruler, priest and indeed god inflicted “the curse of civilisation” on our species of once-happy wanderers. In this reading, the heirs of bullying priest-kings are those politicians and plutocrats who exhibit “acquired sociopathy” and extreme selfishness to a freakish degree – but whose power lets them mould much of society in their abnormal image. A fairy-story this may be, but Bregman tells it winningly well. Besides, the patchy evidence from distant prehistory means that rival narratives have no firmer foundation than his.

Bregman also confronts some tougher evidence to complicate his conviction that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent”. Many evolutionary scientists have argued that altruism emerged to strengthen kin or a wider group – that it amounts to collective selfishness. Babies, he admits, do differentiate very early between Us and Them. He seems to accept that “we’re born with a button for tribalism in our brains”, but that good practice and fair societies can keep it switched off for life. That sounds like a milder version of “veneer theory”. But then Bregman seldom lingers long enough for doubt and ambiguity to seed. His later sections embark on a whistlestop tour around enlightened people and organisations – a healthcare business in Holland, a prison in Norway, an apartheid-era general in South Africa who saw the light – who think and work in ways to re-enforce his belief that “people are hardwired to be kind”. We end, conventionally enough, with the widespread Christmas Truces of 1914 (pictured above) and the realisation that, often in response to German overtures, “fully two-thirds of the British front line ceased fighting” once given the chance. However heart-warming, this scattergun anecdotalism will hardly convert the sort of heavyweight thinker (the likes of Jared Diamond, Steven Pinker and Richard Dawkins) whom this book sets out to challenge and rebut.

Bregman also confronts some tougher evidence to complicate his conviction that “most people, deep down, are pretty decent”. Many evolutionary scientists have argued that altruism emerged to strengthen kin or a wider group – that it amounts to collective selfishness. Babies, he admits, do differentiate very early between Us and Them. He seems to accept that “we’re born with a button for tribalism in our brains”, but that good practice and fair societies can keep it switched off for life. That sounds like a milder version of “veneer theory”. But then Bregman seldom lingers long enough for doubt and ambiguity to seed. His later sections embark on a whistlestop tour around enlightened people and organisations – a healthcare business in Holland, a prison in Norway, an apartheid-era general in South Africa who saw the light – who think and work in ways to re-enforce his belief that “people are hardwired to be kind”. We end, conventionally enough, with the widespread Christmas Truces of 1914 (pictured above) and the realisation that, often in response to German overtures, “fully two-thirds of the British front line ceased fighting” once given the chance. However heart-warming, this scattergun anecdotalism will hardly convert the sort of heavyweight thinker (the likes of Jared Diamond, Steven Pinker and Richard Dawkins) whom this book sets out to challenge and rebut.

That said, Bregman is zestfully good company from first to last. His cheekily entertaining, seductively readable prose finds perfect champions in his translators, Elizabeth Manton and Erica Moore. Meanwhile, his insistence on the solid realism of kindness, compassion and solidarity – with their roots deep in the early growth and flourishing of our species – does offer a more credible account of “the resilience of humankind” than the lurid “killer ape” precepts and their reflections in hyper-individualist politics or economics. And, right now, as mutual care and shared responsibility alone promise a way out of global emergency, it certainly looks as if Bregman and his allies stand on the right side of history.

- Humankind: A Hopeful History by Rutger Bregman, translated by Elizabeth Manton and Erica Moore (Bloomsbury, £20)

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment