Book extract: Holiday Heart by Margarita García Robayo translated by Charlotte Coombe | reviews, news & interviews

Book extract: Holiday Heart by Margarita García Robayo translated by Charlotte Coombe

Book extract: Holiday Heart by Margarita García Robayo translated by Charlotte Coombe

Unusual diagnosis forms the heart of this timely exploration of race, class and the American Dream

Holiday heart, instead of sentimental love discovered on vacation, describes a faltering organ, overloaded from excess consumption: a heart at risk.

“Seeing as he has no history of heart disease, or anything in his heart that would lead us to diagnose any kind of anomaly, I can only conclude that it’s this syndrome…”

As soon as she was inside the hospital – even before going to see Pablo – Lucía headed straight for Ignacio’s office. He’d been her family doctor ever since she’d arrived in New Haven. Ignacio was Chilean but had lived there for decades, and during that time they’d established one of those friendships which enabled them to bypass all the red tape. So, as soon as she got the call from the hospital, she called Ignacio and asked him to check everything out. She was far too anxious to deal with some doctor who didn’t know her and who would certainly underestimate her need to know every minute detail about what was wrong with Pablo, and about any potential treatment.

As soon as she was inside the hospital – even before going to see Pablo – Lucía headed straight for Ignacio’s office. He’d been her family doctor ever since she’d arrived in New Haven. Ignacio was Chilean but had lived there for decades, and during that time they’d established one of those friendships which enabled them to bypass all the red tape. So, as soon as she got the call from the hospital, she called Ignacio and asked him to check everything out. She was far too anxious to deal with some doctor who didn’t know her and who would certainly underestimate her need to know every minute detail about what was wrong with Pablo, and about any potential treatment.

Ignacio was now sympathetically explaining to her, with his elegant mannerisms and measured tone of voice, how arteries worked. On his desk was a small plastic heart sliced in half. He was pointing at it with a laser pen. After the lecture came the diagnosis: her husband was a goddamn party animal. Ignacio was telling her about a disease that affects the cardiovascular system and is caused by excessive consumption of alcohol, red meat, salt, saturated fat and certain drugs. An acquired disease rather than a congenital one, it occurs most commonly during the holiday season, when people get wasted and ignore their expanding waistlines.

“That’s where the name comes from.” Ignacio cleared his throat.

“Huh?”

The syndrome was called Holiday Heart.

A sentimental love song, thought Lucía.

A roadside motel with blinking neon lights.

“In Pablo’s case, this all appears to be accompanied by excessive and, I presume, risky sexual activity.” He cleared his throat again and Lucía, even in her confused state, had the urge to rummage in her handbag and find him a cough drop. “I’m sorry,” said Ignacio, then fell silent.

The silence nurtured the humiliation.

The office’s peach-coloured walls and the small picture frames adorning them – displaying photographs of caterpillars and butterflies that were either cutesy or pornographic, Lucía couldn’t decide which – all had more dignity than her at that moment. What was he sorry about? Was it really so obvious that the risky and excessive sexual activity did not involve her? And then, shattering the brief period of incomprehension due to Lucía’s narcissism, Ignacio revealed that Pablo had been brought to the hospital unconscious, accompanied by an underage girl.

The silence expanded in the seconds that followed, like a plague, building vast totems of humiliation.

Luckily, Pablo was fine, Ignacio said.

Luckily for who?

He went on: it had been a scare, a minor arterial obstruction that had been easy to fix with a stent. At his age, he was perhaps slightly young for a stent, but nowadays it was no biggie – “no biggie”, he said, and she was perturbed by that colloquial expression, like a gob of spit out of a cultivated mouth – lots of men had one, or several.

“Oh, really?”

Yes, Ignacio said. It was fairly common. As long as he took certain precautions, Pablo could return to normal life as soon as he wanted.

When she left the office, she still didn’t go and see Pablo. She ambled down the hospital corridors, taking her time, as if she were visiting a museum. She passed medical students in their apple-green uniforms, crisp and new. Right there, in another wing, Tomás and Rosa had been born. It was an incredibly difficult birth: the doctor had slid her greased-up hands inside Lucía’s cervix and massaged it in a certain way designed to put pressure on the sides, to help dilation, to ease the babies’ passage. It was a painful method, but effective in eighty percent of cases. Lucía couldn’t endure it. She asked them to cut her open. She’d already suffered enough with the pregnancy. Housing two children in one body, she thought at the time, was a forced and unnatural thing. She would open her eyes in the middle of the night, feel her tight, swollen belly, the movement inside, and think: aliens have taken up residence in my body.

Afterwards, once they were out of her, she completely changed her tune. “Very few mammals only give birth to one offspring at a time,” she began to repeat at regular intervals. As the years passed, she convinced herself of her body’s wisdom. By her mid-forties, she wouldn’t have been able to face a second pregnancy, but fortunately she didn’t need to in order to prove that having two children was the perfect measure of motherhood. More was boastful. Fewer was stingy. She was also well-positioned statistically: just a couple of points above American women, who had 1.8 children on average, and a couple of points below Latina women, who had 2.2.

“You can’t have such rigid opinions on everything,” a former colleague said to her, back then, at a get-together of former colleagues. Carla, her name was. She worked at the University of Texas and her career path, seen in perspective, resembled that of a feral cat clawing its way up a skyscraper. “Why can’t I?” Lucía replied. The others looked at her in silence, bulging with morbid fascination. “Because you sound like one of those women who see motherhood as the primary, hypertrophic drive of female existence,” Carla retorted. Lucía looked at her, expecting her to elaborate further, but Carla simply added, “It’s not a good look.” Lucía replied, “Anyway, it wasn’t an opinion, just a close analysis of myself.” “Anyway,” said Carla, “how is it possible to have 1.8 children?”

The others laughed, their teeth all smeared with salmon and cream cheese, olive tapenade and pâté. Sickly tongues. Poisonous eyes.

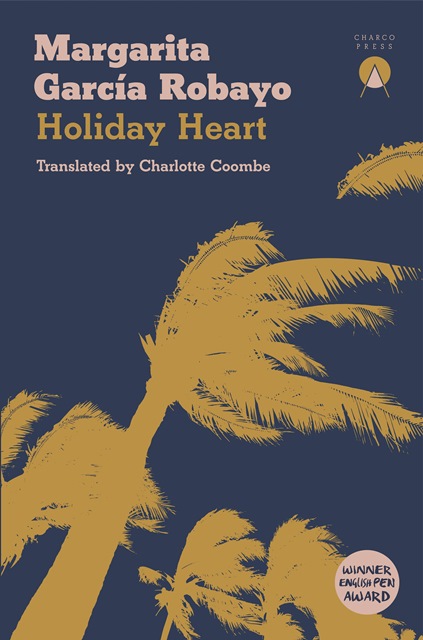

- Holiday Heart by Margarita García Robayo translated by Charlotte Coombe (Charco Press, £9.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment