In 2018, directors Ian Bonhôte and Peter Ettedgui burst onto the documentary scene with McQueen, a visually stunning study of British fashion designer Alexander McQueen. Acclaim and offers followed, but no-one could have predicted the subject of their second feature.

Rising Phoenix is an expansive look at the Paralympics, its athletes, and the wider disability rights movement. Releasing on Netflix this week, the documentary covers the success of London 2012, the fiasco of Rio 2016, and the incredible stories behind the biggest names in para-sport. Owen Richards spoke with directors Bonhôte and Ettedgui ahead of its release:

OWEN RICHARDS: How did you first get involved in this project?

PETER ETTEDGUI: A lot of fashion subjects were being offered to us, which we really didn’t want to do at that time. Neither of us was so interested in fashion that we wanted to have our whole filmmaking careers based around designers.

We were offered this project by Greg Nugent and John Battsek. John is a filmmaker I’ve worked with a lot in the past as a producer at Passion Pictures, and Greg was the guy who was very responsible for the success of London 2012 Paralympics. He’d been the marketing director of both Olympics and Paralympics at London 2012, but he’d become absolutely fascinated and entranced by the Paralympics. It had been his dream from that point to make a documentary about the movement and the Games.

Eight years later he saw McQueen, came to us and asked if we’d be interested. I think immediately, separately, we fell in love with the project. We fell in love with the story of Paralympic founder Ludwig Guttmann. What struck us immediately was a kind of fight of human rights that you’d never heard of. He started this movement on the back lawn of Stoke Mandeville hospital, and it become the third greatest sporting event in the world. We were fascinated by the characters and the whole superhuman angle that Channel 4 had created to promote the Paralympics.

Then, the Rio games were about to cancelled. If we’d written it, you’d have told us it was hokey, but it’s the sort of thing film storytelling structure thrives on. It gives you a twist. We thought people are going to fall in love with this movement, and then you’re going to see it’s all potentially taken away from them.

But we the audience are kind of partly responsible for it. We’ve maybe turned a blind eye to it. We haven’t engaged with people with a disability and impairments. So, it gave us a wonderful storytelling thing straight from the start. We knew we had something that was potentially filmic gold and it was up to us not to screw it up.

You mentioned how Channel 4 presented the London 2012 athletes, and in the film you have quite striking visuals of them as Greek statues, and in artistic poses and locations. What was the thought process behind presenting the athletes in this way?

IAN BONHÔTE: We’re not really into fly on the wall documentaries and getting behind the scenes. On McQueen, we created some really high-end visuals. We felt that we will have the organic and human connection through the personal archives and the documentaries about them already made.

I personally think 90% of documentaries are not visually appealing, and that’s why sometimes audiences are less attracted to them. That’s one aspect.

The other one is many of the athletes never get the chance to be put on a pedestal. Lionel Messi is a really boring, short, small, average looking gentleman; extremely good at one thing, playing with a ball. But throughout his life, he’s been portrayed with this myth around him. Same with Cristiano Ronaldo and all the athletes in sport. That comes from the Greek mythology of the perfect human.

Then, when we started to look into the story of art, anyone with an impairment is generally not looked at. So, we decided to spend the money we had to focus less on the amount of shooting, but shooting them amazingly well. We had Ellie Cole (swimmer) in the pool and looking amazing, Ryley Batt (wheelchair rugby player) fighting a spirit in a warehouse, Bebe Vio (fencer, main picture) walking around a neo-classical renaissance place in Italy. We felt we need to elevate the film visually.

We first came up with the concept of superheroes from the moment Peter and I started to discuss the project. Then on our first interview, Jean-Baptiste Alaize (sprinter and long jump) started talking about superheroes, and that became the intro of the film. We really wanted the visuals of this film to make it impossible to not feel shocked and inspired. Peter said, Channel 4’s superhuman campaign was like, “Oh my god, they’ve done that, we need to do that.”

We developed a technique on McQueen – we like all of the characters we interview to be movie characters. We don’t want to shoot them from the side where it feels a bit weird. We like a strong close up and a wide shot. You get a sense of who they are in the wide shot, and you can show their impairment or whatever, and then that close up where you just concentrate on their emotion. That close up really connects with the audience. What was the process like of choosing which athletes to interview?

What was the process like of choosing which athletes to interview?

PE: Difficult! But fun. We had an amazing team of researchers. They would give us these decks of thousands of athletes, and we could’ve made this film 20 times over with 10 different athletes in each one.

What became important to us is how we represent the breadth of this movement and this world. So, that means not only making sure you have a diversity of cultures, races, but you also have different kinds of impairments or disabilities, people who are born with a disability rather than acquiring one in life. Different sports as well; it would’ve been very easy to make a film with 10 blade runners in, but that would’ve been visually very boring.

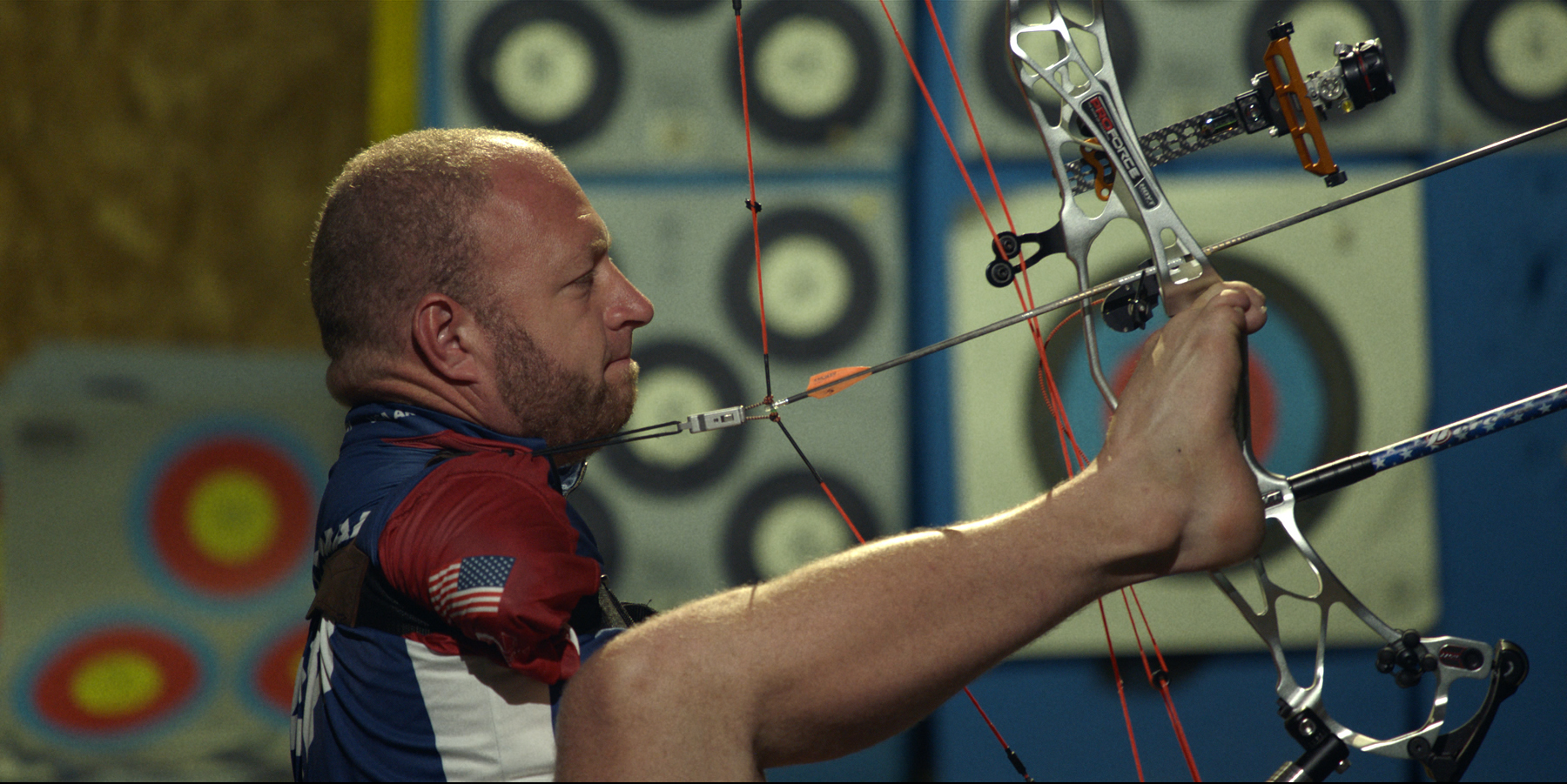

And the most important thing is we have to be gripped by their personal stories. There has to be a diversity of character and personality. Someone like Matt Stutzman (archer, pictured above) gives you this wry sense of humour, but is very different to Jean-Baptiste, who’s very funny as well, but they’re very different characters. So, it’s really thinking about it like a cast.

IB: And the good thing when you’re two directors is if there’s a story you both love, then you know it’s right.

There’s something about sport that makes disability easier to understand for non-disabled people, as a metaphor for overcoming adversity. How important is the Paralympics for furthering disability rights?

PE: Enormously important. The movement was started as part of rehabilitation, as a means to an end, with the end being bringing paraplegics and tetraplegics back into society, at a time when they were just left on the human scrapheap.

And I say at a time, but I watched Crip Camp the other night, there was this institution in 1970s New York, and it’s one of the most horrific things I’ve seen. People with cerebral palsy or severe disabilities were just left lying on the floor. And this was the Seventies, so this is still with us. And the need for something like the Paralympic movement is absolutely necessary.

The Paralympics started as rehabilitation, but at a certain point it became an elite sport. That point was really when people like Sir Philip Craven got a hold of it and said “this isn’t just about helping poor crippled people in wheelchairs to get better, it’s actually something we can do to a very high competitive level, and it’s thrilling to watch.” He really promoted that, and that was at the core of London 2012’s amazing success. It’s part of Philip’s legacy.

Andrew Parsons, the new president of the IPC, was saying to us “we’ve achieved this, the Paralympics has become one of the biggest sporting events on the planet, but we now really need to go back to that aspect of addressing civil rights and integrating people into society. Making sure that people with impairments and disabilities are accepted back into the workplace. There’s a real value in them.”

The Paralympic movement is incredibly important. That’s what attracted us to the film. You have this fantastic sports film on one side, but then you do have this great human rights story. Those two things come together in the Paralympics.

IB: Think about it – when do you have someone with an impairment on television for three weeks non-stop. You don’t. And every four years, as Sir Philip Craven says, there’s this window of opportunity. Yes, you can turn it off, but it’s there. You can’t ignore it.

We found out, and this is partially down to our own ignorance, cities that host the Paralympics have to make changes for the athletes, and for their own people. They have to make sure there’s easy access, etc.

So, the Olympic movement is lovely, it’s sports, someone might go a micro-millisecond faster than Usain Bolt. Thank you very much. But the Paralympic movement is literally changing entire cities, and sometimes entire countries. Look at what happened in Beijing, China.

What’s great about the Olympics and Paralympics is we are very nationalistic. It’s like football. I’m married to my English wife, but suddenly I feel very Swiss, and we have this little friendly competition. The Paralympics means all the nations have to find the best athletes in the country, they have to bring them up. If you want to win medals, do something about it. Train the people. Bring them up young. Inspire them young.

We don’t all look the same, we’re not all size zero. But the Paralympic movement is the one out there showing it through the sport, but it’s way beyond sport. Sport is a tiny part of it, and that’s what we’re trying to show in the film. To that end, what do you think the effect will be to the athletes and the wider movement with the delay of Tokyo 2020?

To that end, what do you think the effect will be to the athletes and the wider movement with the delay of Tokyo 2020?

PE: I think there’s something much more democratic about Covid than there was with Rio. Everyone’s used to the challenges; as they say in the film, if it’s easy, it isn’t the Paralympics. This is small fry compared to what a lot of people are dealing with in their daily lives. It’s small fry in comparison to what happened in Rio.

The effort that has been made in the Tokyo Paralympics to give it parity with the Tokyo Olympics is extraordinary. Talking to the athletes, they all think Tokyo will be bigger than London when it happens. At least, they were saying that before Covid came along. There’s a real sense of anticipation that the Paralympics movement is now on an upward trajectory. It’s not going to suffer the same blips that it did before. And obviously, we’d love it if the film helped cement that reputation that it has in some small way, and make people curious to watch Paralympic sport, tune in for those three weeks.

IB: Of course, we still need to be careful. In the US Open, there was a scandal where they actually cancelled their wheelchair tennis. There was a massive uproar, why would we be cancelled? I agree with Peter, but we can’t stop being vigilant. In that case, they said it could be more dangerous for someone in a wheelchair – that’s BS.

It just shows that no battle is won, and what I’ve taken from doing Rising Phoenix is that the film is a drop in the ocean. The main issue is us as a society and as humans.

How did your own perceptions of disability change throughout the making of the film?

PE: Hugely, to the point where I felt slightly disgusted with myself for not having been more aware and attuned to how one in every 10 people has a difficulty with access because of an impairment, or whatever it might be. I think people very easily turn that blind eye and don’t think more outwardly.

It was noticing things, like most of the tube stations in London are not accessible. We had people with disabilities and impairments working with us on our team, and were suddenly becoming attuned to the challenges they face in everyday life that you’ve never really thought about. I think it does affect you, and it does make you more understanding, compassionate, whatever the word is. It does jerk you out of your easy thinking without any doubt.

We have musicians with disabilities playing on the score and singing the final song, people working with us behind the camera, in the production office, and it’s really helped to normalise it. It changes your perspective because they bring a value, a different perspective to everything you do.

And obviously, on a film like this, it’s crucial because that’s partly what the film is about. But we’d take that into any other film, and we absolutely urge colleagues to do the same.

IB: And for me, it’s using the word "disability", it’s such a small-minded word. If you’re missing one finger, you’re disabled, to not being able to move and speak, you’re disabled. It’s a minefield. And it’s one thing we didn’t approach in the film is the different classifications – you’re judging how “disabled” someone is.

It just shows we’re looking at things completely wrong in our society. We don’t look at the human. We constantly look at putting a sticker or a title on something that is indescribable. The disability community is the world community. There’s everything, every aspect. And I think it’s an insult to fellow brothers and sisters, humans, to put everyone in one pocket.

I think society as a whole is wrong because we go on a rat race, and that means we need to be perfect, we need to be mentally at 100% of our capacities, we need to be beautiful and slim and this and that. I know what the enemy is – it’s society. It’s not us as individuals, because we can spend hours with anyone. Even someone on the most right political spectrum, spend two-three hours with them and you can almost agree on certain things. PE: I think it’s really important, this idea of elite athletes. I think there’s a bad rap for some in the disability community around the whole elite athlete, Paralympic, superhuman thing. On one hand, I understand, but what’s been amazing is discovering every one of the Paralympians we worked with, as well as hundreds and probably thousands of others, they’re not just athletes – they’re human rights activists. They all have their own charities, schools, education programmes.

PE: I think it’s really important, this idea of elite athletes. I think there’s a bad rap for some in the disability community around the whole elite athlete, Paralympic, superhuman thing. On one hand, I understand, but what’s been amazing is discovering every one of the Paralympians we worked with, as well as hundreds and probably thousands of others, they’re not just athletes – they’re human rights activists. They all have their own charities, schools, education programmes.

Jonnie Peacock for example is very much involved with this website called Parasport, which is not about elite sport; if you’re living in somewhere in London for example, where there’s no apparent access to sport, this website will put you in touch with where you should go. And it’s just incredible to see that side.

If you were to ask me what my biggest regret in the film is, and this is partially because this wasn’t the kind of film we’d mapped out, was we didn’t have the space to address that each Paralympian’s life has this aspect of giving back and encouraging. But then, we had some Paralympians that said “so what? I’m an elite athlete. I should have that choice on what I want to do with my life, just as Usain Bolt or Messi.”

Of course, the same choices should be available for someone who’s in a wheelchair, the same possibilities and opportunities.

IB: It would almost be discrimination to say it’s wrong to show them. If it’s an inspiration for certain people, it’s not for everyone. You can’t do everything for everyone, and I’ve learned that. Democracy is about disagreeing, and the more you disagree the more you move forward. So if we’ve got to piss off people sometimes, so be it.

And there is that expectation for a para-athlete that you can’t just be a sportsman, you have to be an inspiration, you have to represent a whole group of people that might not be anything like you.

PE: That’s exactly right, but many of them are.

IB: In the film, we have a lot of the winners. But there’s 20, 30, 40 athletes that didn’t make the qualification, or didn’t make the final. They still trained really hard. We had to make the choice, choose the people. But Jean-Baptiste [Alaize, pictured above] hasn’t won a medal yet.

Peter: And that was very important to us. We didn’t just want to tell the story of the winners.

Ian: You learn a lot from losing, as he says it very well in the film. In London, he didn’t learn about winning but he learned about humanity. That’s part of the message of the film, it’s not just about excellence, it’s about accepting to lose, and trying to do things for yourself and follow your passion. That passion can be about anything.

Add comment