Mark Fisher: Postcapitalist Desire - The Final Lectures review - imagining the alternative | reviews, news & interviews

Mark Fisher: Postcapitalist Desire - The Final Lectures review - imagining the alternative

Mark Fisher: Postcapitalist Desire - The Final Lectures review - imagining the alternative

An eye-opening exploration of the relationship between capitalism and desire

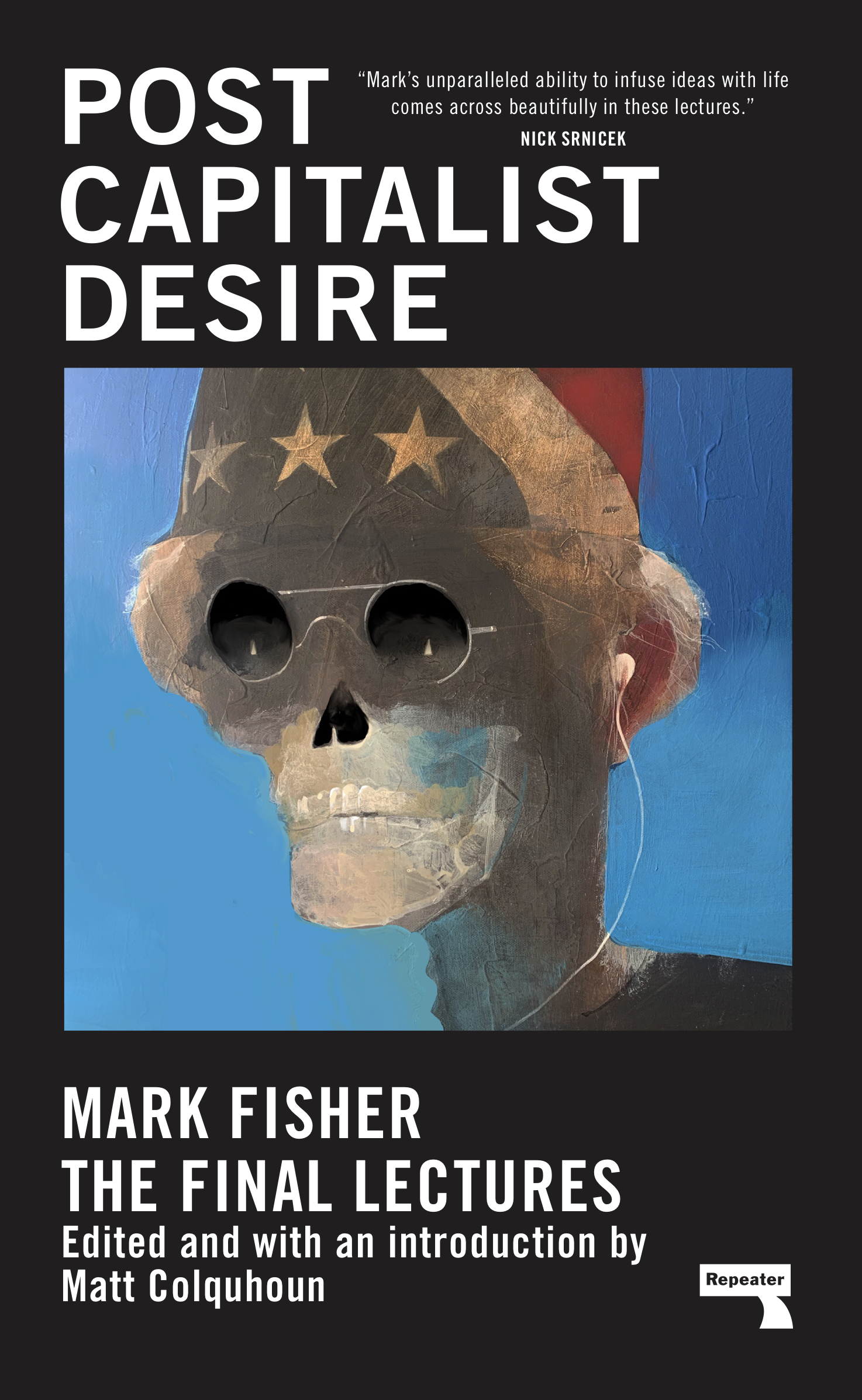

Postcapitalist Desire: The Final Lectures is a collection of transcripts, recording weekly group lectures delivered by Mark Fisher to his students at Goldsmiths, University of London during the 2016/17 academic year.

Capitalist Realism drew attention to a burgeoning paradigm, in which (as per the brief summary Fisher here offers his students) “the idea that there’s no alternative to capitalism becomes the ambient political assumption”. Postcapitalist Desire is then, an extension, or mirror-image of that previous work. It examines the consequences of late capitalism, boring deeper into the antagonisms that seem to plague the contemporary human condition, or “the nefarious and entangled relationship between desire and capitalism, and the extent to which the former can both help and restrict us in our attempts to escape from the latter”. This “escape”, Fisher is keen to stress, must not, cannot, be figured as a return – to a romanticised fantasy of a society before capitalism. Rather, it is to be achieved by moving through capitalism, adopting practical and political transformations to prioritise “working less and determining your own needs”.

Of the 15 scheduled lectures, only the first five are transcribed in this collection. In January 2017, Fisher’s death brought his series to an abrupt halt – at least, in its intended format; the second appendix to the text notes how the class size “doubled, perhaps trebled, in size”. Reading each discussion, it is easy to see why. As lecturers go, one gets the sense that Fisher was probably a good one. Billed as “somewhat theoretical, somewhat journalistic, also some cultural and political history as well”, each week introduces a different perspective relating to the overall theme of postcapitalist desire. Fisher charts a line of decent from the 1970s – through counterculture, trade unions, and the birth of neoliberalism – to the contemporary, where Fisher’s insights really shine through. Take, for instance, his analysis of so-called “identity politics”. It is wrong, Fisher argues, to understand the phenomenon as a game played only by the left. Instead, he makes the point that the crafting of an identarian working class, in the US and the UK, has been essential to the success of the right, and entails a deflation of traditional class consciousness: “They bring class and race together in order to negate the transformative potentials of both”. To Fisher, these developments are no accident. Rather, “it’s a deliberate strategy at the level of capital and human consciousness.”

Of the 15 scheduled lectures, only the first five are transcribed in this collection. In January 2017, Fisher’s death brought his series to an abrupt halt – at least, in its intended format; the second appendix to the text notes how the class size “doubled, perhaps trebled, in size”. Reading each discussion, it is easy to see why. As lecturers go, one gets the sense that Fisher was probably a good one. Billed as “somewhat theoretical, somewhat journalistic, also some cultural and political history as well”, each week introduces a different perspective relating to the overall theme of postcapitalist desire. Fisher charts a line of decent from the 1970s – through counterculture, trade unions, and the birth of neoliberalism – to the contemporary, where Fisher’s insights really shine through. Take, for instance, his analysis of so-called “identity politics”. It is wrong, Fisher argues, to understand the phenomenon as a game played only by the left. Instead, he makes the point that the crafting of an identarian working class, in the US and the UK, has been essential to the success of the right, and entails a deflation of traditional class consciousness: “They bring class and race together in order to negate the transformative potentials of both”. To Fisher, these developments are no accident. Rather, “it’s a deliberate strategy at the level of capital and human consciousness.”

Extracted from the real-life lecturing environment, the book is, nevertheless, surprisingly easy to follow – a fact that owes itself, in no small part, to Matt Colquhoun’s excellent introduction. Fisher, meanwhile, has an evident knack for well-judged digressions, dwelling where necessary on the trickier, complex points of contention. It is only in the final lecture, “Libidinal Marxism”, which takes up the not-quite critique of Marx and Marxism in Jean-François Lyotard’s Libidinal Economy (1974), where Fisher runs the risk of losing his students (and now, his reader). This is, however, a symptom of the notorious complexity of Lyotard’s text, and Fisher does a fine job of rendering its claims intelligible. If not, the problem is easily remedied – Fisher’s reading list has been helpfully included as an appendix to the book, enabling those who wish to follow the course right through to its intended conclusion.

The lectures contained within Postcapitalist Desire bear an irresistible socio-political significance. Yet, it is perhaps Fisher’s doubts and hesitations, his lack of pretension to a complete understanding of the topics at hand, that give the text its main attraction. Towards the end of Fisher’s first seminar, a discussion around the implementation of a Universal Basic Income spurs a student to pose a question regarding inflation. “Oh God…”, Fisher replies, “I don’t know anything about economics, really…” – cue group laughter. We may well wonder: how feasible is it, to request faith in any critical and cultural project in light of such a glaring aporia? Yet, rushing in to fill the gap, Fisher’s relentless optimism, his ambitious commitment to imagining an alternative to capitalism, is what makes him and Postcapitalist Desire so enjoyable.

- Postcapitalist Desire: The Final Lectures by Mark Fisher (Repeater Books, £12.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Add comment