First Person: pianist Filippo Gorini on head, heart and the contemporary in Bach's 'The Art of Fugue' | reviews, news & interviews

First Person: pianist Filippo Gorini on head, heart and the contemporary in Bach's 'The Art of Fugue'

First Person: pianist Filippo Gorini on head, heart and the contemporary in Bach's 'The Art of Fugue'

Taking off from a masterly marriage of rigorous means and expressive ends

A past work of art either still speaks to us in the present, or it is dead. To try and understand a masterpiece, we tend to look at its past: we study it, analyse it, read biographies of the artist behind it and chronicles of its historical background. But it is even more interesting to see what happened to the work after it was finished. What did it mean to the following generations, and, more critically, what does it mean to us today?

No other composer has influenced future generations in the same measure as Johann Sebastian Bach. His timeless compositions are so perfectly crafted that every detail feels essential, with no hint of superfluous material or excess. Every note has a meaning, a purpose, deeply connected with a deep conception of the world, life, and divinity. And yet, they seem to translate effortlessly to any artistic language: there can be beauty in a romantic interpretation of Bach just as in an historically informed one, or a jazz improvisation, contemporary transcription, or visual adaptations whether in theatre, dance, or art. I always found it curious that this supposedly very objective and mathematical music ended up showing most openly the soul of whoever is performing it, to the point that one can understand almost everything about a musician from just a couple of minutes of their playing of Bach.  This could not be more true when one talks about The Art of Fugue, Bach’s last, unfinished work. It has a legendary status, being revered to the point of fear even among musicians’ circles. Around 90 minutes of pure conatrapuntal music, written in the most rigorous style, with compositional complexities that no other composer ever managed to tame. When I was very young, it was always presented to me as a sort of intellectual abstraction, a pure speculation that had little to do with emotion. I did not pay much attention to it at the time: I had no interest in music that did not speak to the heart.

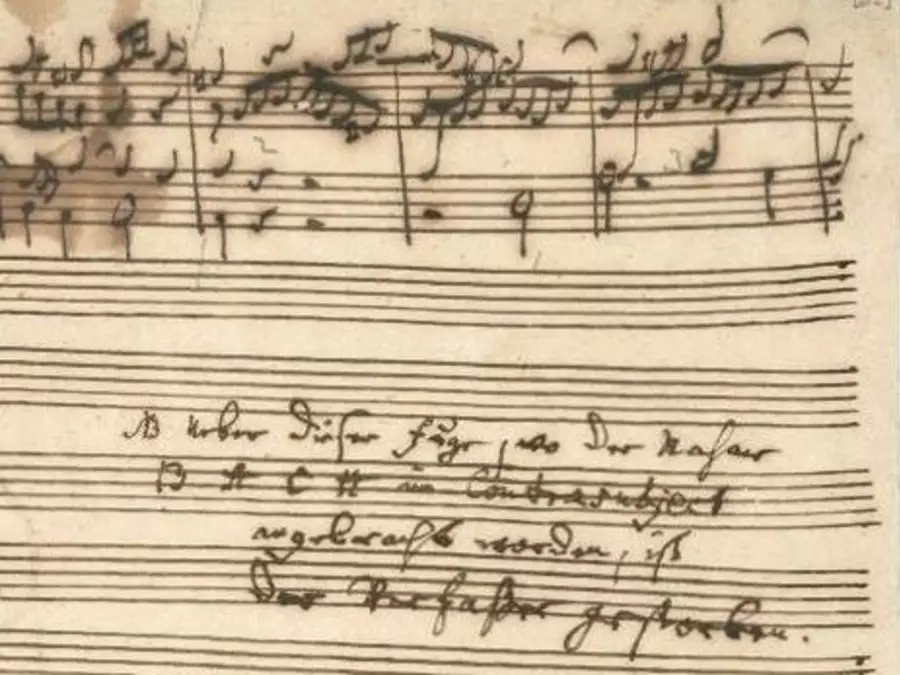

This could not be more true when one talks about The Art of Fugue, Bach’s last, unfinished work. It has a legendary status, being revered to the point of fear even among musicians’ circles. Around 90 minutes of pure conatrapuntal music, written in the most rigorous style, with compositional complexities that no other composer ever managed to tame. When I was very young, it was always presented to me as a sort of intellectual abstraction, a pure speculation that had little to do with emotion. I did not pay much attention to it at the time: I had no interest in music that did not speak to the heart.

About eight years ago, Sergio Vartolo, an exquisite harpsichordist who was teaching at my conservatory at the time, invited me to try learning two of these counterpoints, reading them from the full score rather than the two-staves reduction for keyboard players, taking the time to understand polyphony from the inside. I fell in love with this music. It was beautiful on every level: whether I read about its history, or analysed the structure of the fugues, or explored the inventive harmony Bach employed to meet his expressive demands, on no level did this piece fail to astonish and move me.

Most of all, I found that playing it and listening to it was in fact an incredibly powerful experience, and the notion that this was music not meant for the heart started to feel simply ridiculous. The composer Lachenmann says it better than anyone else: when one believes that reason and sensibility inhibit each other, it really means that both these faculties are underdeveloped. In The Art of Fugue, complex intellectual means are necessary to express more and more poignant and spiritual contents, leading into a journey that really does change one’s life once experienced.

Most of all, I found that playing it and listening to it was in fact an incredibly powerful experience, and the notion that this was music not meant for the heart started to feel simply ridiculous. The composer Lachenmann says it better than anyone else: when one believes that reason and sensibility inhibit each other, it really means that both these faculties are underdeveloped. In The Art of Fugue, complex intellectual means are necessary to express more and more poignant and spiritual contents, leading into a journey that really does change one’s life once experienced.

Over the following years, I kept working on this piece slowly, in the background. It is not easy to learn to play this type of composition, and even less so to start feeling somewhat at ease, and, dare I say, free, in the intricacies of these fugues. I had just received the Borletti-Buitoni Trust Award when the pandemic started, and it was clear that I would have a lot of time on my hands, while also having support and funds to start an artistic project of my choosing. This is how “The Art of Fugue Explored” was born.

It is an exploration, because the more I looked into this work, the less I felt like I had answers, but rather maybe interesting pathways that others might also want to walk. The first step was to finally perform and record the work, committing what is my current interpretation to an album on Alpha Classics. In my playing, I tried most of all to keep the work emotionally intense, to make the polyphony clear, and to maintain the sense of a single, long journey, rather than many separate fugues. To my inner ear, the work had to be sung by human voices, and the piano should be a singing instrument. I did not want to shy away from using its full dynamic capabilities and the sustain pedal where the intensity of the voices and the harmonies they created seemed to call for extreme colours. I also had another idea: to associate each counterpoint with a figure of the contemporary cultural scene, and film with them conversations about Bach’s music and why it mattered so much in their life and work. To my surprise, artists whose work shaped my whole life were immediately willing to take part in this. The architect Frank Gehry, the opera director Peter Sellars and film director Alexander Sokurov, the artists Anselm Kiefer and Alexander Polzin, the dance choreographer Sasha Waltz and musicians such as Alfred Brendel, Mitsuko Uchida, Steven Isserlis, and Helmut Lachenmann all welcomed my idea to try and express the deep relationship between Bach, The Art of Fugue, and our present. The travelling and safety restrictions slowed down the filming significantly, but more and more people began to help me and believe in this project, and it should see the light of day soon enough.

I also had another idea: to associate each counterpoint with a figure of the contemporary cultural scene, and film with them conversations about Bach’s music and why it mattered so much in their life and work. To my surprise, artists whose work shaped my whole life were immediately willing to take part in this. The architect Frank Gehry, the opera director Peter Sellars and film director Alexander Sokurov, the artists Anselm Kiefer and Alexander Polzin, the dance choreographer Sasha Waltz and musicians such as Alfred Brendel, Mitsuko Uchida, Steven Isserlis, and Helmut Lachenmann all welcomed my idea to try and express the deep relationship between Bach, The Art of Fugue, and our present. The travelling and safety restrictions slowed down the filming significantly, but more and more people began to help me and believe in this project, and it should see the light of day soon enough.

Even as I write, more and more ideas are taking shape involving film and visual arts, and just as The Art of Fugue is unfinished, so it seems like my work on it will only get more intensive and dedicated. There is nothing I could welcome in my artistic life than to make such an eternal masterpiece its centre for many years, and my hope is I can bring this seemingly difficult work close to the heart of whoever will choose to listen to me, and to the work of the many, many people who are supporting me and joining me in this incredible journey. To them, and to my listeners, I will always bear boundless gratitude.

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Hallé John Adams festival, Bridgewater Hall / RNCM, Manchester review - standing ovations for today's music

From 1980 to 2025 with the West Coast’s pied piper and his eager following

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Kaploukhii, Greenwich Chamber Orchestra, Cutts, St James's Piccadilly review - promising young pianist

A robust and assertive Beethoven concerto suggests a player to follow

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Robin Holloway: Music's Odyssey review - lessons in composition

Broad and idiosyncratic survey of classical music is insightful but slightly indigestible

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Classical CDs: Wolf-pelts, clowns and social realism

British ballet scores, 19th century cello works and contemporary piano etudes

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Add comment