American artist Kehinde Wiley may be best known for his photo-realist portrait of Barack Obama, but painting powerful black men is not the norm. More often he elevates people met on the street in Brooklyn, Dalston or Dakar to positions of pseudo authority by inserting them into pastiches of history paintings honouring the rich and powerful.

A black guy replaces Napoleon, for instance, in Wiley’s take on Jean-Auguste Ingres’ 1806 portrait of the Emperor seated on his throne. Wiley’s model sits on Napoleon’s gorgeous ermine cape, but the red velvet robes and laurel wreath have been replaced by casual day wear and a jaunty black cap.

To 21st century eyes, Ingres’ portrait looks ridiculously pompous – an ostentatious piece of theatre intended to make a little man look big – so the theatricality of Wiley’s version is perfectly in keeping. The key difference, of course, is that Napoleon wielded real power, whereas the posturing of Wiley’s model is make-believe, unless, that is, you take into account the fact that, with his toned body, the black man is physically far superior to the weedy white man. One kind of power is measured against another.

Wiley’s paintings are never straightforward reversals of the tradition, then. Nor is it altogether clear what he is trying to do. His models are beautiful and he accords them enormous dignity and pride. Inserting black people into the canon is a reminder of their former absence, but it does little to ameliorate their exclusion or to alter the balance of power which it reflects.

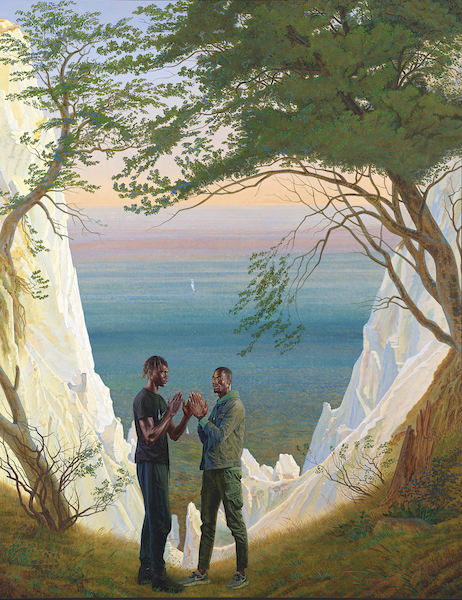

Then there’s the self-conscious artifice of the project. Take, for instance, Wiley’s version of Caspar David Friedrich’s Chalk Cliffs on Rügen,1818 (pictured right), one of the paintings that inspired the National Gallery show. Impeccable draughtsmanship enables him to copy Friedrich’s landscape perfectly. In the original, three people (the artist, his wife and brother) gaze over the cliff edge in awe. They are tiny compared with a landscape whose magnificence is an invitation to contemplate God’s creation and our place within it.

Then there’s the self-conscious artifice of the project. Take, for instance, Wiley’s version of Caspar David Friedrich’s Chalk Cliffs on Rügen,1818 (pictured right), one of the paintings that inspired the National Gallery show. Impeccable draughtsmanship enables him to copy Friedrich’s landscape perfectly. In the original, three people (the artist, his wife and brother) gaze over the cliff edge in awe. They are tiny compared with a landscape whose magnificence is an invitation to contemplate God’s creation and our place within it.

Wiley replaces them with two much larger figures who stand in the centre of the picture, ignore the view and play pat-a-cake. They look superimposed, like cut-outs divorced from their surroundings; one even stares back at us, as though challenging us to expel him. Then there’s the colour; heightening the subtle hues of the original to the point of kitsch, Wiley transforms Freidrich’s spirituality into icing-sugar sublime devoid of any hint of romanticism. Maybe he wants to highlight our loss of connection with nature, but the jarring disjunction still makes the picture look wrong and undermines its credibility.

Until now the artist has mainly concentrated on painting, but here the pictures function as an introduction to the main event – a six-screen projection of his film Prelude (main picture), similarly inspired by romantic painters and writers, such as William Wordsworth and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

Wiley took a group of black Londoners from Soho to Norway and filmed them in the snow-bound emptiness of mountains, lakes and forests. They look dramatically out of place in the inhospitable whiteness – a compelling metaphor for living as a black person in a world controlled mainly by whites.

Colourful clothing – yellow, orange and red anoraks – marks them out even further from their monochrome surroundings. They are not dressed for the cold yet seem determined to pit themselves against it. Some gingerly pick their way through deep snow in flimsy boots; two women, their hair plaited into a huge top-not, brave strong winds and two guys expose their naked chests to the elements. The footage is very beautiful. Firelight turns everything red (pictured below) and, to emphasise the contrast between comfort and cold, a shot of the air filled with sparks cuts to blizzard conditions. A young man quotes Emerson: “We are as much strangers in nature, as we are aliens from God. We do not understand the notes of birds... We do not know the uses of more than a few plants, as corn and the apple, the potato and the vine…”

A young man quotes Emerson: “We are as much strangers in nature, as we are aliens from God. We do not understand the notes of birds... We do not know the uses of more than a few plants, as corn and the apple, the potato and the vine…”

In the most compelling sequence, five individuals smile to camera; snowflakes snagging in their hair, eyebrows and lashes, they hold their ground for long minutes as the camera glides in for a close-up, then pulls back only to return and reveal muscles twitching under the strain of holding a fixed grin. It’s like torture. Is this what true resilience looks like – being able to maintain a smile under adverse circumstances?

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment