theartsdesk at the Ravenna Festival 2022 - body and soul in perfect balance | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at the Ravenna Festival 2022 - body and soul in perfect balance

theartsdesk at the Ravenna Festival 2022 - body and soul in perfect balance

Completion of the city’s big Dante project with 'Paradiso' is only one of three wonders

For once, a festival theme has meaning. “Tra la carne e il cielo”, “Between flesh and heaven”, is how Pier Paolo Pasolini, the centenary of whose birth we mark this year, defined his early experience of hearing the Siciliana movement of Bach’s First Violin Sonata (adding that he inclined to the fleshly). It provided the perfect epigraph to the four Ravenna Festival performances I attended this year, three of them as stunning as any hybrid event I’ve ever witnessed.

The choice of return dates – regretfully missing out on Riccardo Muti's "Roads of Friendship" this year, though I did by chance catch the chorus of the Ukrainian National Opera rehearsing Mozart and Verdi with Italian counterparts in a church converted into a concert space – was down to an overwhelming experience with the second instalment in the dramatisation of Dante’s Divina Commedia, Purgatorio, in 2019. The inspirational leading lights of Ravenna’s Teatro delle Albe, Marco Martinelli and Ermanna Montanari, national heroes of the theatre in Italy and well known in the rest of the EU and the USA, but not as yet in the UK, started with Inferno in 2017. Purgatorio followed two years later and the triptych was due in 2021. It wasn’t even possible to stage just Paradiso then because of ongoing restrictions (though there was a marathon reading to keep the flame alive).

Finally, last week, there we were again, outside Dante’s tomb for the reading of the first canto before joining another processional of citizen-performers and spectators, led this time by trombone rather than trumpet (Raffaelo Marsicano, pictured below by Silvia Lelli with Martinelli and Montanari), this time to a spectacularly-managed destination in the Public Gardens.  As everyone gathered on Thursday evening, first signs of the predicted storm began – drops of rain and rumbles of thunder. Our Dante and Beatrice told us we’d have at least the beginning and take a rain check, which happened in the cloisters of Ravenna’s City Art Museum, housed in the former Abbey of Santa Maria in Porto backing on to the gardens. With forked lightning now dramatically regular, and the rain coming down, if not in torrents (Ravenna was spared the golfball hailstones which hit Modena), the venture was abandoned. A lucky few, myself included, could come back on Friday – the last night both of the production and of my time in Ravenna.

As everyone gathered on Thursday evening, first signs of the predicted storm began – drops of rain and rumbles of thunder. Our Dante and Beatrice told us we’d have at least the beginning and take a rain check, which happened in the cloisters of Ravenna’s City Art Museum, housed in the former Abbey of Santa Maria in Porto backing on to the gardens. With forked lightning now dramatically regular, and the rain coming down, if not in torrents (Ravenna was spared the golfball hailstones which hit Modena), the venture was abandoned. A lucky few, myself included, could come back on Friday – the last night both of the production and of my time in Ravenna.

So follow me via the other events first, if you will. All were unknown quantities, optional extras. But two were transforming. The first evening’s destination was the Artificiere Almagià, home to the Teatro delle Albe’s friends in another important Ravenna theatre company, Fanny & Alexander/E Productions. It was surprising when built in 1887 as a sulphur warehouse taking the shape of a basilica (you’d still think it was a converted church). Its restoration was included in the city’s impressive redevelopment of the harbour area (where in 2019 I had an inspiring cookery lesson from Rosella Mengozzi in the nearby pop-up complex alongside the River Candiano; I enjoyed another in Rosella’s home this year, and intend to make tagliatelle agli spinaci with pesto sauce from now on).

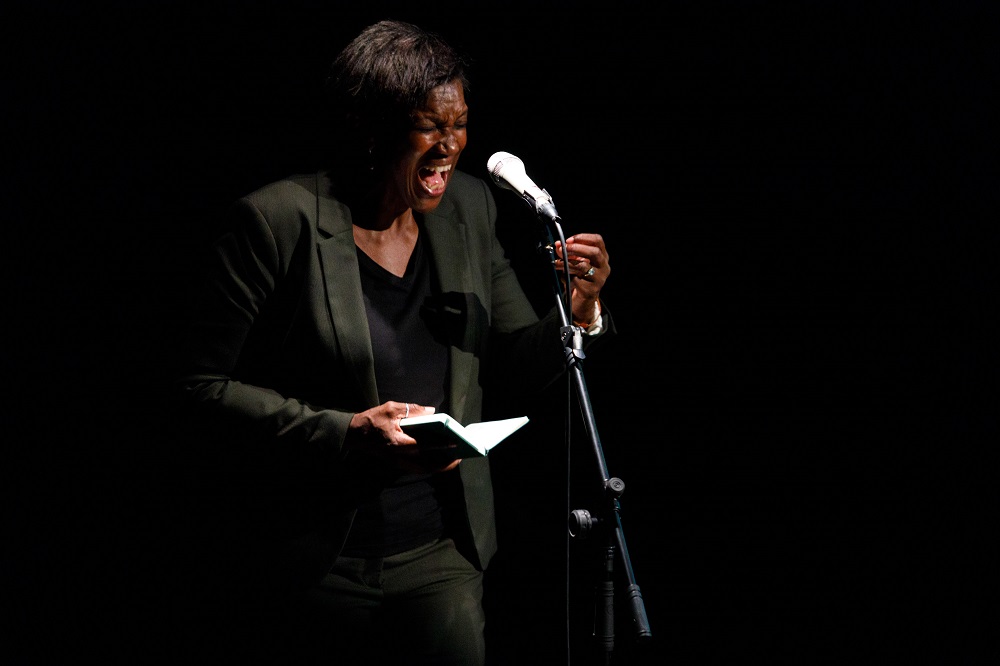

I knew the first-class artistry of American soprano Claron McFadden (pictured below in the first of two images by Marco Parollo), from an impressive role in Handel’s Ottone at St John’s Smith Square in the mid-1980s to a 2010 Bernstein spectacular with fellow music-theatre stunner Roberta Alexander. So I was expecting her role in The Garden: A Contemporary Passion to be good; but what of the electronics and the visuals?  As it turned out, everything was of the highest possible artistic quality. Composer Emanuele Wiltsch-Barberio enhances rather than diminishes works by Arvo Pärt, JC Bach, Giovanni Legrenzi, Barbara Strozzi, Dowland and Monteverdi by live-looping McFadden’s chameleonic delivery, itself spanning three octaves: the polyphony in the motet version of “Lasciatemi morire” is more or less pure, the Dowland supremely haunting, and when McFadden is allowed to be vocally alone, in “Strange Fruit”, her delivery is as valid as the classics by Billie Holliday and Nina Simone.

As it turned out, everything was of the highest possible artistic quality. Composer Emanuele Wiltsch-Barberio enhances rather than diminishes works by Arvo Pärt, JC Bach, Giovanni Legrenzi, Barbara Strozzi, Dowland and Monteverdi by live-looping McFadden’s chameleonic delivery, itself spanning three octaves: the polyphony in the motet version of “Lasciatemi morire” is more or less pure, the Dowland supremely haunting, and when McFadden is allowed to be vocally alone, in “Strange Fruit”, her delivery is as valid as the classics by Billie Holliday and Nina Simone.

The concept of Fanny & Alexander’s Luigi De Angelis for his “Video-concerto Polyptych” is perfectly realised. On six smaller screens flanking a big central one, we see moving images of people we assume to be activists or prisoners of conscience from Africa through to Syria and Hong Kong (they are all actors, which could be disconcerting if you knew them, as I was told by a Teatro delle Albe actor who so admired the results). An equally beautifully filmed olive grove, seen at first in spring, provides the only other visual component.  These, it soon emerges, serve seven stages in a Passion (three have names: "Gethsemane", "Pilato" and "Ecce Homo"). The actors have no speech, so it’s all the remarkable how much the suited, tie-wearing Pilate (pictured above) manages to convey of guilt in authority. There is no catharsis: the brave folk are all seen in death; Pilate waltzes with another bureaucrat. The whole thing demands a lot of its audience – after all, the musical pieces are essentially eight Adagios, or at least slow movements – but its communicative power is undeniable; it deserves to be seen in other festivals round the world.

These, it soon emerges, serve seven stages in a Passion (three have names: "Gethsemane", "Pilato" and "Ecce Homo"). The actors have no speech, so it’s all the remarkable how much the suited, tie-wearing Pilate (pictured above) manages to convey of guilt in authority. There is no catharsis: the brave folk are all seen in death; Pilate waltzes with another bureaucrat. The whole thing demands a lot of its audience – after all, the musical pieces are essentially eight Adagios, or at least slow movements – but its communicative power is undeniable; it deserves to be seen in other festivals round the world.

As does Virtual Dance for Real People, performed before a necessarily small audience in Ravenna’s Biblioteca Classense, still very much a working library. We met in the room where a glorious Roman mosaic found near Sant’Apollinare in Classe has been rehoused, peacock central – but in this case with a central railway track over it. The two dancers of the National Dance Foundation/Aterballetto, Philippe Kratz and Grace Lyell, sit with closed eyes on chairs above movable platforms at either end. He stirs, he summons her to life, their eyes hardly leave each other. In big boots fixed to the platforms, holding their feet fast, they bend to unbelievable degrees. The platforms slowly slide to bring them together (pictured below by Zani-Casadio). Finally they touch. Then they are separated again. This was a powerful metaphorical, mythic theme to develop during lockdown, and it remains so. The two performers are beautiful, compelling to watch; their gravity-defying moves bring tears to the eyes.  In what I’d see as an optional extra, still marvellous, choreographer Fernando Melo invited each of us "to give up the comfort of the fourth wall to become an active participant in the performance": we had a chance to replay the drama at close quarters through visual headsets and earphones. Tthe special bonus here was that the action switches between the Sala del Mosaico and another part of the library that the public doesn’t get to see (shown in the lead image). The technology may not be life-changing, but the dance absolutely is.

In what I’d see as an optional extra, still marvellous, choreographer Fernando Melo invited each of us "to give up the comfort of the fourth wall to become an active participant in the performance": we had a chance to replay the drama at close quarters through visual headsets and earphones. Tthe special bonus here was that the action switches between the Sala del Mosaico and another part of the library that the public doesn’t get to see (shown in the lead image). The technology may not be life-changing, but the dance absolutely is.

With paradise postponed, I wondered if I could catch the fourth event I was scheduled to see. Given a half-hour start on Paradiso, and the fact that I could join the that processional after the reading of the first Canto, I could. The principle and Marco Gatta’s text for the operatic monodrama Storia di un Figlio Cattivo (History of a Mean Son) are both excellent: a dramatisation of Augustine of Hippo’s shift from naughty boy to saintly one as seen through the words and eyes of his conservative mother Monica, updated to give contemporary significance but with plenty of lines from Augustine’s letters, and a final twist: he’s killed in a brothel just when his mother thinks he’s beatific.

She doesn’t read the transformative final lines from a final epistle, but we hear them. The main flaw in the performance is the location, the Basilica of San Vitale, one of the six main mosaicked treasures of Ravenna, certainly the grandest, and brought into the action with a light on the central Lamb of God in the apse's dome (pictured left by Zani-Casadio). This is a chamber opera more suited to a space like the Artificiere Almagià, and the words of mezzo-soprano Daniela Pini were lost in reverberation; a great pity, for she’s a superlative singer and actor. Filippo Bittasi’s score is more monotonous, too often a generic impasto, with a few transcendental moments, but very well performed by the Ensemble Tempo Primo and organist Andrea Berardi.

She doesn’t read the transformative final lines from a final epistle, but we hear them. The main flaw in the performance is the location, the Basilica of San Vitale, one of the six main mosaicked treasures of Ravenna, certainly the grandest, and brought into the action with a light on the central Lamb of God in the apse's dome (pictured left by Zani-Casadio). This is a chamber opera more suited to a space like the Artificiere Almagià, and the words of mezzo-soprano Daniela Pini were lost in reverberation; a great pity, for she’s a superlative singer and actor. Filippo Bittasi’s score is more monotonous, too often a generic impasto, with a few transcendental moments, but very well performed by the Ensemble Tempo Primo and organist Andrea Berardi.

After the end, I found the Paradiso performers – as in Purgatorio, white-clad citizens of Ravenna as well as professional actors and musicians – passing Sant’Apollinare Nuovo on their way to the garden of paradise. Each night a different musical group sings at the approach to the gallery – on the rained-off evening, a superb local choir singing madrigals, on the final night a Nigerian group from a local Baptist church who also danced. At the gate Martinelli and Montanari mark us with the sign of Dante’s ultimate celestial vision, “three circles, of three colours and one circumference”.  The citizens were already atmospherically in place under the pine trees on either side of the Loggetta Lombardesca, the chief glory of the gallery, from which Santa Maria in Porto took its name (I’d never seen it on previous visits to Ravenna).

The citizens were already atmospherically in place under the pine trees on either side of the Loggetta Lombardesca, the chief glory of the gallery, from which Santa Maria in Porto took its name (I’d never seen it on previous visits to Ravenna).

Pietro Lombardo’s beautiful work is graced by five newish-looking mannerist statues on the upper level, musicians playing Luigi Ceccarelli’s as ever fine-tuned score below. Little angels on bicycles were whizzing round as we took our seats. The statues live as five of the characters Dante meets in the different planets and sun of his journey upwards: Piccarda Donati; Justinian, whose speech metamorphoses into a furious tapestry of Pope Francis’s invectives against world poverty, natural despoliation and greed; Cunizza da Romano; San Pier Dammiani; and San Pietro. Dante’s life of St Francis is acted out with exuberant Indian dancing to express the joy of that life. Ensembles can be ghostly, exultant or absolutely terrifying: fingers in ears as the musical sounds become deafening. (pictured above by Silvia Lelli: bread about to be distributed among the spectators). A solo voice (Mirella Mastronardi in Aramaic-rendered Psalm 51) or dancer (Montanari as whirling sufi) draw us back to the individual.

Two final stages bring lucidity. Martinelli expounds so clearly on the “eyes-led-upward” achievements of Bernini and Borromini in Rome that I understood every word, and I’m now halfway through the first book I’ve ever read in Italian, his Nel Nome di Dante (In the Name of Dante). Those two geniuses will, it seems, be the next subject of Teatro delle Albe’s roving intelligence. Finally, he tells us that we may remain seated or come forward and lie on the five circular coverings the citizens have laid out while Montanari so beautifully reads the final canto (pictured below by Silvia Lelli).  Doing so means we see the stars becoming visible one by one. And as they, stelle, are the last word in each cantiche, what could be more transcendent? It was splendid to be asked to join in the communal feast afterwards, and good to see African Muslims in their finest boubous making their way to the mosque to celebrate Eid-Al-Adha as I enjoyed my coffee and brioche the next morning – no wonder I was teary about departing – but the final sense of the infinite, the best stargazing possible without a telescope, will stay with me for ever.

Doing so means we see the stars becoming visible one by one. And as they, stelle, are the last word in each cantiche, what could be more transcendent? It was splendid to be asked to join in the communal feast afterwards, and good to see African Muslims in their finest boubous making their way to the mosque to celebrate Eid-Al-Adha as I enjoyed my coffee and brioche the next morning – no wonder I was teary about departing – but the final sense of the infinite, the best stargazing possible without a telescope, will stay with me for ever.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment