theartsdesk at the Ravenna Festival - Italians, Ukrainians and an American promote peace | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk at the Ravenna Festival - Italians, Ukrainians and an American promote peace

theartsdesk at the Ravenna Festival - Italians, Ukrainians and an American promote peace

Muti, Malkovich and friends glow in the city of transcendental mosaics

Everything is political in the world's current turbulent freefall. The aim of Riccardo Muti's "Roads of Friendship" series, taking the young players of his Luigi Cherubini Youth Orchestra to cities from Sarajevo in 1997 to Moscow in 2000 and Tehran last year, has simply been "to perform with musicians from different cultures and religions" in a community of peace.

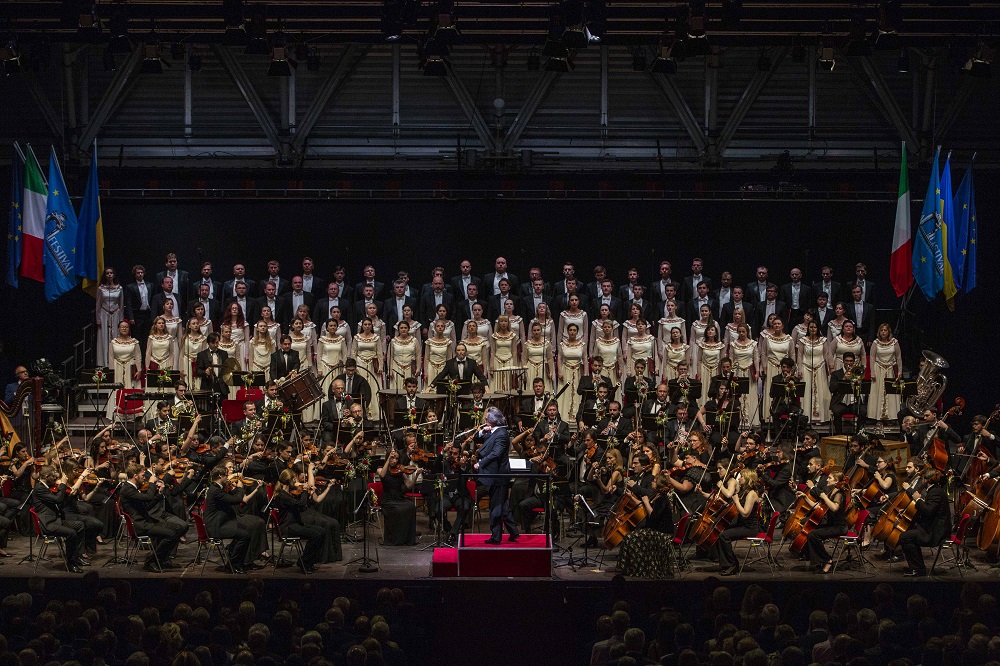

That they were evinced through the highest artistry was never in doubt. And given the big concert's stupendous repeat spectacular as well as a very beautiful choral concert below the stunning apse mosaics of Sant' Apollinare in Classe (pictured below), peace predominated back in Ravenna. Italy may be going through a rocky time, too, but the Ravenati, despite a past closeness to Mussolini, tend to the left, and their home is a haven of tranquillity. Verdi knew that the musical could also be political when he had his chorus of Hebrew slaves yearn for their homeland in Nabucco; to hear the magnificent voices from the Ukrainian National Opera blaze at the fortissimo on "patria" was one of several spine-tingling, tear-jerking moments in an evening of superb music making. It is, of course, a wonder in itself to hear the world's greatest living conductor of Italian opera plunge one with authoritative ease into the drama of the Nabucco Overture, to make every phrase live in a second half of substantial excerpts from that opera.

Verdi knew that the musical could also be political when he had his chorus of Hebrew slaves yearn for their homeland in Nabucco; to hear the magnificent voices from the Ukrainian National Opera blaze at the fortissimo on "patria" was one of several spine-tingling, tear-jerking moments in an evening of superb music making. It is, of course, a wonder in itself to hear the world's greatest living conductor of Italian opera plunge one with authoritative ease into the drama of the Nabucco Overture, to make every phrase live in a second half of substantial excerpts from that opera.

Here we heard a total star as the fire-breathing Abigaille, an insane part which needs the steel of a Lady Macbeth, fearless top Cs and tender lyricism. In Kiev the big aria had been taken by a known flame-toned diva, Lyudmila Monastyrska; here it was Oksana Kramaryeva, fresh as a substantial daisy in long, controlled phrases and with the temperament you dream of in these roles. Though she's a soprano, I hope she will set London ablaze as Eboli and possibly even Azucena. Such a voice with musicianship to match comes along very rarely. You can be sure that Muti coached her extensively on the Italian.

Even he had a harder job making everything connect in the more diffuse worlds of the Stabat Mater and Te Deum of Verdi's Four Sacred Pieces (pictued below) at the start of the concert, though there were inspirational moments. The deep highlight of the entire evening, in the massive Palazzo Mauro De Andrè, playing to a packed audience of 4,000 – and with wholly successful, natural-sounding amplification, by the way – was the collaboration between Muti, his musicians and the ever-charismatic John Malkovich in Copland's Lincoln Portrait.  This touched on the wider theme of the festival which, it must be stressed, is the brain-child of the conductor's generous and ever-present wife, Cristina Mazzavillani Muti; despite his presence in the central event, the nearly two-month spread of events in Ravenna is not his. The festival's hero this year is Martin Luther King. Its title, "We Have a Dream"/"A j o fat un sogn", gives the cue to a wider Americana, embracing the Bernstein Centenary, Opera North's brilliant Kiss Me, Kate, Terry Riley, Keith Jarrett, David Byrne, the ubiquitous Glass, the Bill T Jones/Arnie Zane Company, 100 electric guitars playing inter alia Glenn Branca and Jimi Hendrix, and even a trekking/boating event outside Ravenna on the protected nature reserve of the Lago di Comacchio marrying local music with blues guitar from the Mississippi delta. Wish I'd been there for that one, though I did enjoy the strangeness of the place on an excursion to Comacchio itself, a little Venice which used to be centre of the extraordinary eel-catching industry.

This touched on the wider theme of the festival which, it must be stressed, is the brain-child of the conductor's generous and ever-present wife, Cristina Mazzavillani Muti; despite his presence in the central event, the nearly two-month spread of events in Ravenna is not his. The festival's hero this year is Martin Luther King. Its title, "We Have a Dream"/"A j o fat un sogn", gives the cue to a wider Americana, embracing the Bernstein Centenary, Opera North's brilliant Kiss Me, Kate, Terry Riley, Keith Jarrett, David Byrne, the ubiquitous Glass, the Bill T Jones/Arnie Zane Company, 100 electric guitars playing inter alia Glenn Branca and Jimi Hendrix, and even a trekking/boating event outside Ravenna on the protected nature reserve of the Lago di Comacchio marrying local music with blues guitar from the Mississippi delta. Wish I'd been there for that one, though I did enjoy the strangeness of the place on an excursion to Comacchio itself, a little Venice which used to be centre of the extraordinary eel-catching industry.

We think of Malkovich as a magnetic crooner and whisperer. This is the first time I've heard him declaim with power and contained anger. Famously he'd distanced himself from politics up to and including the last American election, but he can't be happy now. The words of Lincoln as chosen by Copland against a panoply of proud brass and strings – Muti got the Italian-Ukrainian orchestra to launch in with another display of shining power – came as a tearful catharsis after two weeks of horror peaking in the child-caging monstrosity. Pardonable to blub, then, when Malkovich proclaimed "It is the eternal struggle between two principles, right and wrong, throughout the world. It is the same spirit that says 'You toil and work and earn bread, and I'll eat it.'...As I would not be a slave, so I would not be a master." Context was much both here and in the Chorus of the Hebrew Slaves, but the actual delivery of both could not have been surpassed.

Beneath it, the Kiev participants from the previous evening gave spellbinding performances of slightly less transcendental odes to the glory of God. Silvestrov's Elegy and Pastoral for piano and orchestra and his Cantata No. 4 in the first half need perhaps a little more grit in the celestial oyster; this is not pure minimalism by any means, but its distinctive melodic shapes promise more than they ultimately give.

In another league altogether are his Liturgical Songs of 2005 – a sequence which would make an admirable choice for any good choir wanting to avoid the inevitable Rachmaninov or Tchaikovsky Vespers. Chordal progressions are rich and unexpected; the layering and the abundant solo devotions keep us good company throughout. Again, the metaphysical dimension just evades Silvestrov. He might blame that on the choir, whom he pooh-pooed with a disgraceful display of pique when he took his bow; apparently he hadn't been satisfied with their dynamic levels at the rehearsal, but a professional saves the criticism for later. To me, this was as much of a vocal-richness thrill as the displays of the peerless Glinka Academic Cappella of St Petersburg. No western choir could hope to match it; and the dimension of operatic voices, still able to blend perfectly as a whole, was spine-tingling in the individual contributions. Silvestrov redeemed his bad temper to a certain extent with a piano-solo encore on the cusp of audibility, only the playing saving the piece in question from Claydermanesque banality (pictured below).  As for the mosaics, back within the city/town, you move in a dreamlike trance from one of the eight Unesco World Heritage sites to another, nothing daunted by the summer heat since the streets are shady, the distances minimal and other tourists largely absent (the Italians are at the sea in July, I was told, and maybe foreign visitors think cities are too hot in the summer; this one, which feels more like a friendly village, couldn't be more pleasant). They range from the astonishing domes of the two baptisteries, the smaller perhaps the most magical if not as naturalistic, and the intimacy of Galla Placidia's blue-and-gold Mausoleum to the golden cloudbursts of San Vitale.

As for the mosaics, back within the city/town, you move in a dreamlike trance from one of the eight Unesco World Heritage sites to another, nothing daunted by the summer heat since the streets are shady, the distances minimal and other tourists largely absent (the Italians are at the sea in July, I was told, and maybe foreign visitors think cities are too hot in the summer; this one, which feels more like a friendly village, couldn't be more pleasant). They range from the astonishing domes of the two baptisteries, the smaller perhaps the most magical if not as naturalistic, and the intimacy of Galla Placidia's blue-and-gold Mausoleum to the golden cloudbursts of San Vitale.

Having just been saturated in the rainbow hues of Dante's Paradiso, I could well believe that in the peaceful last years of his life, an exile welcomed in Ravenna, he was influenced to translate the visual miracles he saw around him into gorgeous words. The quiet "Zona Dante," where his much-moved-about remains are contained in a pretty chapel, is another welcome place to retreat from the heat. He is, unquestionably, the town's local god; but the Ravenati are also very fond of King Theodoric the Goth, whose brief rule from 493 to 526 AC gave the place not only the wonders of Sant' Apollinare Nuovo and the Arian Baptistery but also a peaceful time in which various religious sects lived together in harmony before Justinian, who never came here, shed the blood of the Arian Christians. For that reason the much-loved benefactor, an outsider promoting tolerance, makes a very good unofficial patron saint for a festival of peace and harmony.

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment