"This," Lizzie Graham writes in the programme book of the current Longborough Festival, “is definitely the test of whether or not it is possible to put on a convincing Ring in a small, privately-owned country theatre.” I don’t think Lizzie or her husband, Martin, the festival’s founders and owners of the theatre, can have seriously doubted that the answer would be yes. Serious doubts seem not to be part of their entrepreneurial make-up; or if they are, they suppress them. But the noisy acclaim of the far from provincial or rustic audience at the end of Götterdämmerung on Saturday must all the same have been music to their ears. The cycle had been not just convincing but, beyond question, a huge triumph, demolishing at a stroke all kinds of prejudice about Wagnerian scale, the Wagnerian orchestra, even the Wagnerian voice.

Longborough’s 500-seat converted-barn theatre with its modest pit (70 players maximum) is not quite what you would think of designing for a 15-hour cycle with a cast of 50 and an orchestra of 110. But numbers can be deceptive. Gotthold Lessing’s reduced orchestral version of The Ring, made in the 1940s for small provincial German theatres, fits Longborough like a glove, mainly because it allows (though it doesn’t specify) a reduction of Wagner’s large string section – frankly unnecessary in a theatre this size.

Refinements of gesture and facial expression come into play to an extent almost unknown in the bigger houses

Just occasionally in Götterdämmerung and in the third act of Siegfried one misses the sheer weight of sonority that Wagner, in his late style, seems to be wanting. But hardly anything of the colour and variety, even richness, of his orchestration is lost in the superb playing of the festival’s orchestra under Anthony Negus. One of Negus’s assistants told me that the pit goes back so far that the woodwind sections, far under the stage, are sometimes practically inaudible to the singers. The balance for the audience, though, was consistently excellent – a rarity in Wagner; and as for any problems of pit-to-stage coordination, I detected none.

On the other hand there are positive gains in terms of scale. The fact that the audience is so comparatively close to the stage means that refinements of gesture and facial expression come into play to an extent almost unknown in the bigger houses that usually perform Wagner. This is a major factor with Rachel Nicholls’s Brünnhilde, a truly great performance that humanizes this character to a degree unknown in my experience before her own début in the role last year, without in the least diminishing its epic force.

My impression is that Nicholls’s voice, bred in baroque and classical music, has expanded since 2012 and acquired a more brilliant top. It remains, though, an instrument under nearly perfect control, with none of the squalling and squawking that Wagner sopranos like to use in their running battle with the orchestra. Nicholls, as I noted last year, sings this music with the precision and musicality, if not always the verbal clarity, of a lieder-singer. I wondered last year whether she would ever manage it in a large theatre. I now believe she would.

My impression is that Nicholls’s voice, bred in baroque and classical music, has expanded since 2012 and acquired a more brilliant top. It remains, though, an instrument under nearly perfect control, with none of the squalling and squawking that Wagner sopranos like to use in their running battle with the orchestra. Nicholls, as I noted last year, sings this music with the precision and musicality, if not always the verbal clarity, of a lieder-singer. I wondered last year whether she would ever manage it in a large theatre. I now believe she would.

Before last week, I had seen only the Siegfried and Götterdämmerung of Alan Privett’s production. In some ways Das Rheingold – musically the least rangy of the four operas – is the trickiest to stage in a small house. More than its successors, it depends heavily on movement, magic and illusion, and it can’t be said that Privett solves this problem with his permanent trio of visible, black-tighted stagehand actresses, who lift a black cloth to vanish Alberich or turn him into a nonexistent giant snake, or with his helplessly arm-waving Rhinemaidens, inertly defending the swirl of reddish-gold fabric, alias the Rhinegold, that Alberich pinches without serious opposition.

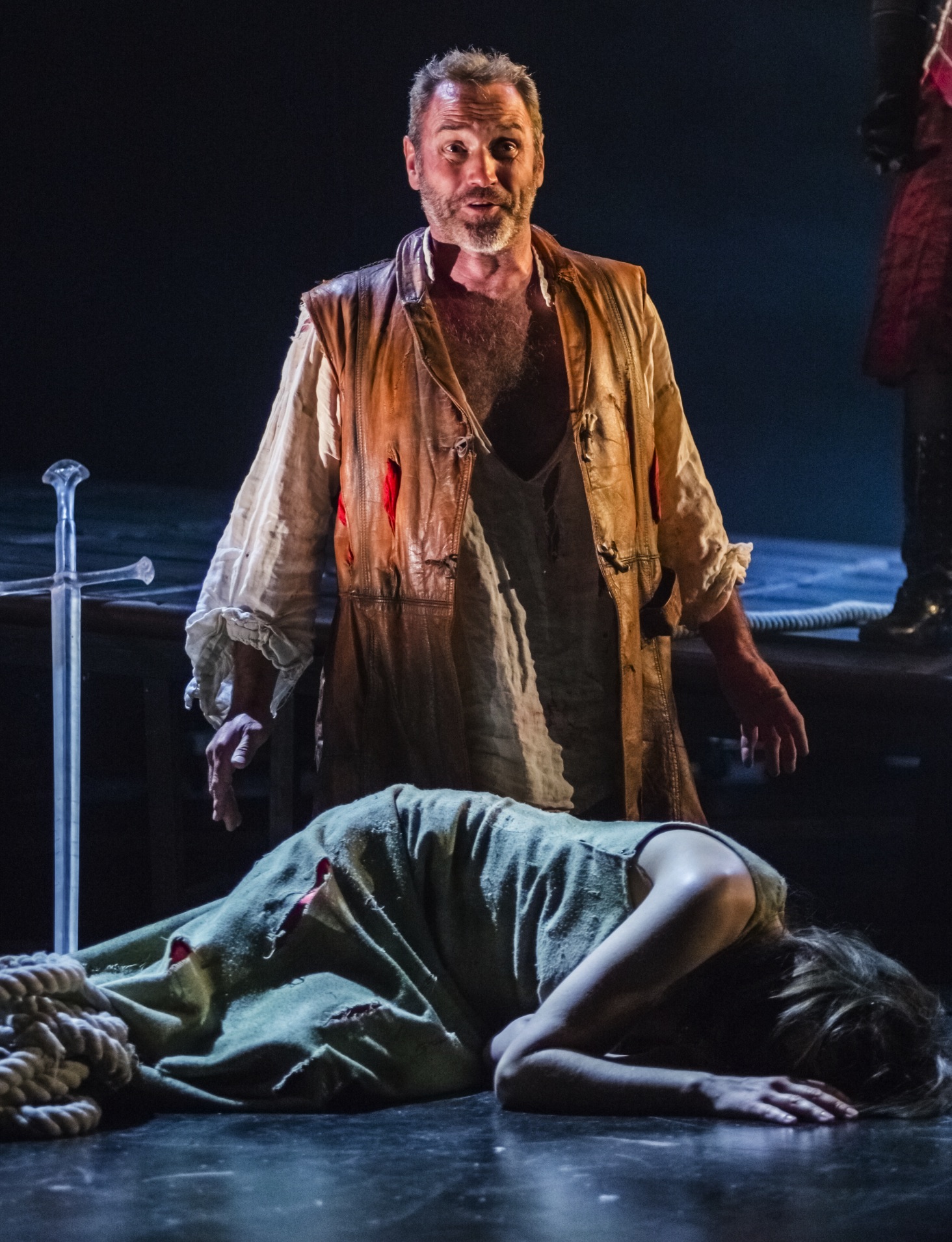

Things liven up sharply with the entry of Mark Le Brocq’s vibrantly physical Loge (pictured above by John Alexander) in the second scene. Le Brocq, as well as being a fine lyrical singer, is another performer, like Nicholls, who understands the virtues of facial expression and quick, reactive gesture, which he uses like a television actor, assuming an attentive close camera. Perhaps he even overdoes it now and then; or is it just the rather static environment that makes it seem that way?

Continued overleaf

Privett himself seems much happier with Die Walküre, the most intimate panel of the tetralogy, and the one that depends most on richly evolved dialogue between pairs of characters. Suddenly there is movement and chemistry: a beautifully poised Sieglinde in Lee Bissett (already a touching, interesting Freia in Rheingold), and a splendiferous Siegmund in Andrew Rees (pictured below together by Matthew Williams-Ellis), who, however, perhaps let rip a shade too much in the early scenes and ran into vocal problems thereafter.

The second act confrontations are riveting. Jason Howard’s Wotan, rather inhibited in Rheingold, blooms both vocally and psychologically in his third-degree with Alison Kettlewell’s magnificent Fricka, a portrait finely touched in with the ironic smiles and cutting gestures of the subservient, controlling wife. Then come Wotan and Brünnhilde, Brünnhilde and Siegmund, and in the final act the long farewell scene, Howard and Nicholls wonderfully interactive, the whole act – including a stunning team of Valkyries arriving from boxes and galleries, too many for individual praise - immaculately paced by Negus and subtly lit, like much of the production, by Ben Ormerod.

touched in with the ironic smiles and cutting gestures of the subservient, controlling wife. Then come Wotan and Brünnhilde, Brünnhilde and Siegmund, and in the final act the long farewell scene, Howard and Nicholls wonderfully interactive, the whole act – including a stunning team of Valkyries arriving from boxes and galleries, too many for individual praise - immaculately paced by Negus and subtly lit, like much of the production, by Ben Ormerod.

Since 2011 Privett has made changes to Siegfried, and a few, I think, to Götterdämmerung. Fafner (the dark-voiced Julian Close) no longer trundles in on a cherry-picker, but hides behind a trio of sinister spot-lamps, then dies in his human shape: a distinct improvement. But the scene here and elsewhere is cluttered: gantries and scaffoldings that say nothing and block up the stage. As before, no leaf or blade of grass picks up the music’s insistence that we are in a forest; only the Woodbird, sparklingly sung and fluttered by Gail Pearson, survives of the Wagnerian flora and fauna.

Mime, Siegfried and Alberich are double-cast. In Rheingold Richard Roberts is presumably standing in as Mime for Adrian Thompson in the first two cycles (of the three), but does so skilfully and with a certain malicious charm. In the dwarf’s much bigger Siegfried role, Thompson sheds the playfulness in favour of a rampant malevolence barely concealed by smarmy amiability, while catching the trace of poetry Wagner found in the poor little trickster. This is an excellent musical portrait. By contrast Malcolm Rivers, the Alberich here and in Götterdämmerung, has less vocal warmth than his Rheingold opposite number, Andrew Greenan (he is, after all, in his late seventies), but compensates with superb projection and a vivid presence, shuffling and scowling, and spitting out his words like cherry stones.

Longborough have found a pair of more than adequate Siegfrieds. Hugo Mallet (in Siegfried itself) showed signs of under-preparation: he missed a couple of entries and once or twice needed prompting. But he sang with ease and clarity, moved well, and has the inestimable virtue, in this part, of looking like a descendant of the Master himself. In Götterdämmerung Jonathan Stoughton seems entirely secure in the part: no blond Aryan, this Siegfried, but a dark, smiley, randy Hollywood star, all hands and eyelashes when he meets Gutrune, the innocent small-town boy not showing much sign of the wisdom Brünnhilde claims to have bestowed on him. The voice is strong and bright, but apt to lose colour in the softer middle register. On the whole it’s a reading that draws out the main weakness of Wagner’s central idea: the image of the Greatest Hero as not much more than a tough cowboy who don’t scare easy but gits nervous with the ladies.

This is not a Ring of strong or alienating concepts. We are mainly in an ill-defined mythic epoch until Götterdämmerung, where for some reason the Gibichungs turn up in lounge suits and dresses or, in Hagen’s case, a snazzy brown housecoat (pictured left in mauve light by Matthews-Ellis: Stoughton, Pendred, Wade). They even go hunting in this kit, a limitation of wardrobe that perhaps explains Gunther’s poor standing along the Rhine. The castings, though, are strong, as last year. Eddie Wade is excellent as the weak, indecisive Gunther, who affects a wheel-chair to excuse his avoidance of heroic action; Stuart Pendred is good as the half-caste Hagen, though the voice, admirably focused in general, doesn’t always carry well from upstage; Lee Bissett is again lovely as Gutrune, a third portrait for her finely-differentiated gallery.

This is not a Ring of strong or alienating concepts. We are mainly in an ill-defined mythic epoch until Götterdämmerung, where for some reason the Gibichungs turn up in lounge suits and dresses or, in Hagen’s case, a snazzy brown housecoat (pictured left in mauve light by Matthews-Ellis: Stoughton, Pendred, Wade). They even go hunting in this kit, a limitation of wardrobe that perhaps explains Gunther’s poor standing along the Rhine. The castings, though, are strong, as last year. Eddie Wade is excellent as the weak, indecisive Gunther, who affects a wheel-chair to excuse his avoidance of heroic action; Stuart Pendred is good as the half-caste Hagen, though the voice, admirably focused in general, doesn’t always carry well from upstage; Lee Bissett is again lovely as Gutrune, a third portrait for her finely-differentiated gallery.

Who does that leave? Three superb Rhinemaidens (Gail Pearson, Sara Wallander-Ross and Catherine King); three amazingly mellifluous Norns (Wallander-Ross, King and Meta Powell) perched ten feet up on their cherry-pickers – one of designer Kjell Torriset’s most striking images. Some memorable individual vignettes: Geoffrey Moses’s pale, sentimental Fasolt, Julian Tovey’s fine, no-nonsense Donner, Stephen Rooke, a Froh who for two minutes sings like the fourth tenor, Mark Richardson’s perfectly unrefined Hunding. Phillip Joll returns as the Wanderer, but the voice is losing focus and clouds the solemnity of the musical line, notwithstanding the authority of his presence.

But perhaps the most telling memory will be of Anthony Negus, the brilliant Svengali of this whole extraordinary week, crowding the stage at the final curtain, not only with the singers, but with everybody else in the company, down (or up?) to the tea-ladies, who has had any involvement in making the event what it is. It was a nice touch, and one that precisely reflected the range, as well as the scale, of Longborough’s achievement.

Add comment