Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream opens with creepy glissandi emanating from the pit like nocturnal spirits. There is no mention in the score – this is an educated guess – for the chirrup of swifts and the hoot of wood pigeons, but this avian chorus joined the overture anyway at last week’s dress rehearsal in the open-air courtyard of Théâtre de l'Archevêché. Perhaps director Robert Carsen ordered them in as an atmospheric extra. An Aixtra, if you will.

Carsen’s Dream has returned to Aix-en-Provence, at the Festival d'Art Lyrique where it began all the way back in 1991. Remarkably given its great age, the old warhorse still has the ravishing sheen of youth upon it. Where some productions which go on and on turn into tottering monoliths, bent double by the burden of their own illustrious history, there is nothing weary about this Dream.

Beds are famous places for dreaming, also for sex. It’s a very hormonal opera

“It’s remarkable to me that we are still doing this,” Carsen tells me the afternoon before the final dress. “We couldn’t have conceived that it would have the success that it has and that people would feel so warmly towards it.” Carsen is a dapper Canadian, still gamin at 61, who went on to make himself a fixture in the opera houses of Europe and America. His Falstaff has just returned in triumph to the Royal Opera House (theartsdesk review hailed Carsen's "consummate gift for visual transformations") and his Rinaldo was back at Glyndebourne last summer ("ingenious and witty," said theartsdesk). He also regularly flits across to musical theatre.

None has the legs of his Dream, which in 13 revivals has been all around the houses - in Lyons (the supplier of the slender orchestra in Aix under Kazushi Ono), the Coliseum, Barcelona (where it was filmed for DVD release) and most recently La Scala. But its true home, Carsen acknowledges, is in the outdoors where Britten’s notion of a midsummer night can commune with the real thing. “There is a particular meeting of the opera and its place in this theatre. There’s a moon onstage and if you look up you can see the real one.” Its opening tableau remains a delightful coup de théâtre which draws gasps from audiences: the curtain rises to reveal a raked stage in the form of a vast bed covered in a sylvan green blanket, which Britten’s chorus of boy fairies – dressed in green tails, blue trousers and crimson mittens, and sung here by Trinity Boys Choir choristers (pictured above) – draw back to reveal vast white pillows nestling on a white sheet. “I was trying to find a metaphor for the forest,” recalls Carsen. “It’s very difficult putting nature onstage. What I do not want to do is fake trees. When you make them fake it just somehow has a deadening effect when you’re trying to capture the feeling of what it’s like to be in the forest.” (Carsen’s feelings about trees were amusingly enshrined when Mitros Yerolemou as Puck emptied his bladder on a real tree growing in the courtyard).

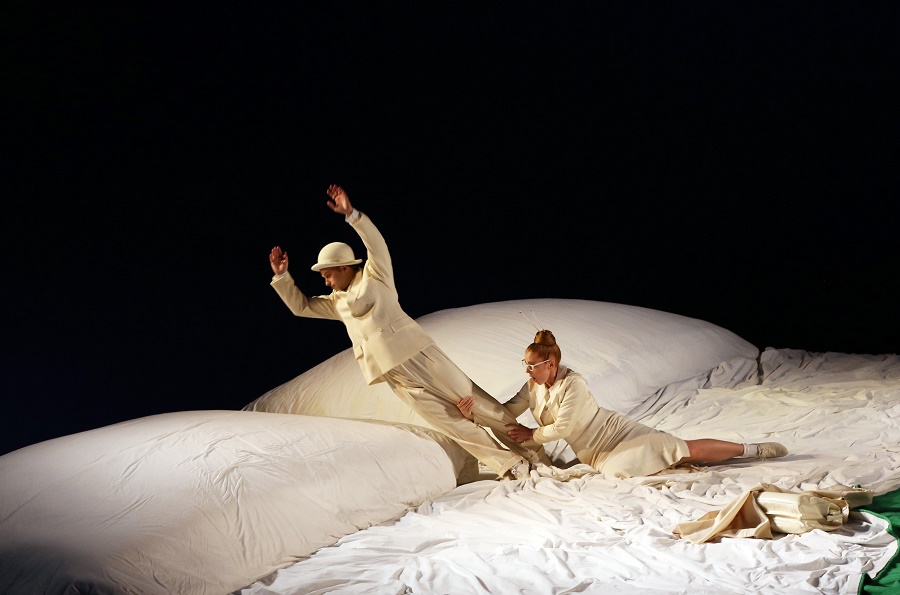

Its opening tableau remains a delightful coup de théâtre which draws gasps from audiences: the curtain rises to reveal a raked stage in the form of a vast bed covered in a sylvan green blanket, which Britten’s chorus of boy fairies – dressed in green tails, blue trousers and crimson mittens, and sung here by Trinity Boys Choir choristers (pictured above) – draw back to reveal vast white pillows nestling on a white sheet. “I was trying to find a metaphor for the forest,” recalls Carsen. “It’s very difficult putting nature onstage. What I do not want to do is fake trees. When you make them fake it just somehow has a deadening effect when you’re trying to capture the feeling of what it’s like to be in the forest.” (Carsen’s feelings about trees were amusingly enshrined when Mitros Yerolemou as Puck emptied his bladder on a real tree growing in the courtyard).

“I thought, if we make the whole thing a bed,” continues Carsen, “that might be a wonderful way of dealing with the problem. Beds are famous places for dreaming, also for sex and there’s a lot of sex in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. It’s a very hormonal opera.” (Pictured below: John Chest as Demetrius and Layla Claire as Helena) Later the stage starts to crowd with beds like a bucolic dormitory, and come act three they are suspended above the stage, before miraculously drifting up into the fly tower, dragging the entire carpet of bedding with them to expose the white, pristine world of the Athenian court. The production’s return 24 years on encountered a difficulty pulling off this magical transformation. Alison Walker, the production manager tasked with realising Levine’s designs, recalls that in 1991 the Théâtre de l'Archevêché was a temporary structure put up for the summer, and it accommodated a tall fly tower that breached Aix’s historical skyline. The production has returned to find a permanent slat-fronted theatre, with much less storage room above the stage.

Later the stage starts to crowd with beds like a bucolic dormitory, and come act three they are suspended above the stage, before miraculously drifting up into the fly tower, dragging the entire carpet of bedding with them to expose the white, pristine world of the Athenian court. The production’s return 24 years on encountered a difficulty pulling off this magical transformation. Alison Walker, the production manager tasked with realising Levine’s designs, recalls that in 1991 the Théâtre de l'Archevêché was a temporary structure put up for the summer, and it accommodated a tall fly tower that breached Aix’s historical skyline. The production has returned to find a permanent slat-fronted theatre, with much less storage room above the stage.

One thing that hasn’t changed is the particular problem of lighting a show in the outdoors. In 1991, the Dream was a late add-on to the festival’s schedule and there was barely any access to the theatre beforehand. Carsen borrowed a sweltering gymnasium in which to work out some basic lighting, but once in the outdoor theatre itself this could only be fully tested between midnight and dawn. And that’s still the case now. “Which is why we’re all so tired.”

The cast for this year includes the ethereal pairing of French soprano Sandrine Piau and American countertenor Lawrence Zazzo as Tytania and Oberon (respectively bewigged in blue and green, pictured below) and Lancastrian bass Brindley Sherratt larking about as big-eared Bottom. Christopher Gillett, who was Flute in 1991, is back as Snout. The other long-serving cast member is Yerolemou, a gifted product of Jacques Lecoq school of clowning who plays the non-singing Puck as a sort of tumbling rubber-ball, at two points hurling himself off the back of the raked stage. The part in the production was conceived for Emil Wolk, and 22 years ago Yerolemou was his understudy at the Coliseum when he was still far too young to embody Carsen’s vision of a wizened old fairy. “I’d just come out of drama school,” he recalls, “and my agent said, ‘I’ve got a casting for you. It’s for an opera.’ I was like, “I don’t even read music!” I’d never even seen an opera. Emil became my mentor. Then he did his back in and I had to do the first performance without knowing anything.” Two decades on, he has made Puck his own (having also taken time out to play Bottom in Bristol Old Vic’s 2013 collaboration with Handspring Puppet Company). What with Yerolemou’s ability to work a crowd, and the mechanicals’ amateur dramatics in the final act (pictured below), I can’t recall ever hearing laughter like it at an opera.

Two decades on, he has made Puck his own (having also taken time out to play Bottom in Bristol Old Vic’s 2013 collaboration with Handspring Puppet Company). What with Yerolemou’s ability to work a crowd, and the mechanicals’ amateur dramatics in the final act (pictured below), I can’t recall ever hearing laughter like it at an opera.

Down the road outside the old historic centre in the modern Grand Théâtre de Provence, Peter Sellars unveiled a Russian double bill of one-act operas: Tchaikovsky’s last opera Iolanta about a blind princess, and Perséphone, Stravinsky’s unhappy collaboration with André Gide. They make a natural match, both exploring the theme of female entrapment and escape. The same austere set on a bare stage do for both operas, a quartet of steel door frames with random blocks of sculpture stuck to the cornicing like freshly landed fragments of meteor. Tchaikovsky’s final opera is more captivating, musically and dramatically. Ekaterina Scherbachenko, her searing blue dress supplying the only colour, excels as the blind Iolanta as does Willard White as the shaman who gives her sight.

As for Perséphone, it is no Rite of Spring. Gide embarked on the collaboration enthusiastically. “Total agreement,” he confided to his diary in 1933. A year later, after the first performances in Paris had not gone down well, Stravinsky accused him of “complete absence of rapport, which obviously originated in your attitude”. There are only two singing roles, but there was a third element in a creative ménage à trois in the form of Ida Rubinstein’s choreography. That has been jettisoned by Sellars in favour of four Cambodian dancers from Amrita Performing Arts.

The double bill is one of three operas in Aix supported by the festival’s Chinese partners, the KT Wong Foundation, which promotes Sino-European cross-cultural exchange. As well as Carsen's Dream, there is Jonathan Dove's community opera The Monster in the Maze. The Dream is also being shown at the MISA festival in Shanghai next week under the aegis of the Foundation. (The others are Robert Lepage's The Nightingale and Patrice Chéreau's Elektra). A Midsummer Night’s Dream continues its Chinese adventure next year when it celebrates its 25th anniversary as a guest of the Beijing Music Festival. (Pictured below: Christopher Gillett as Snout and Brindley Sherratt as Bottom) Lawrence Zazzo, who is expecting to continue as Oberon in China, has a hunch that this globe-trotting Dream will speak to a Chinese audience. “Britten had said when he was composing it that he was very much influenced by Balinese music and you can hear that in the percussion,” he says. “And for me a clear association is with Chinese classical opera. They use something like a countertenor – men singing in this falsetto register – so that’s a bit of a bridge into this music for an audience in Beijing. It’ll be very interesting to see how they react to it.”

Lawrence Zazzo, who is expecting to continue as Oberon in China, has a hunch that this globe-trotting Dream will speak to a Chinese audience. “Britten had said when he was composing it that he was very much influenced by Balinese music and you can hear that in the percussion,” he says. “And for me a clear association is with Chinese classical opera. They use something like a countertenor – men singing in this falsetto register – so that’s a bit of a bridge into this music for an audience in Beijing. It’ll be very interesting to see how they react to it.”

In Aix the Dream is still being received rapturously. Even the semicircular curtain call, with the stars flanked by the immaculate Trinity Boys Choir in their livery, is a little theatrical masterpiece. How long can the show go on? I ask Robert Carsen in the hot afternoon as the bells of the neighbouring Cathédrale Saint-Sauveur prepare to clang for evening mass.

“I don’t see that there’s any reason to stop,” he says with a smile of shy bravado. “So it can go on for another 25 years. If anyone wants it.”

Add comment