I’m sitting in the Olivier waiting for the show to start, comfortable in the knowledge that I’ve seen the original production of Mnemonic, one of Complicité’s most lauded plays, in 1999; but I struggle to remember anything about it, the detail is fuzzy. A play about memory is challenging my own faltering apparatus.

Who did I see it with? Where? What was that audience participation? I sift through the gears, opening mental doors in an attempt to find a clue as to whether I did actually see it, after all. Meanwhile, the magnificent Kathryn Hunter, stalwart of the Complicité troupe, takes her seat a few feet away, here to support her colleagues; and her presence takes me elsewhere, with an indelible image of another play, her bestriding a stage as the diabolical, misshapen, vengeful, tragic Frau Zachanassian in The Visit. That’s all I need, a concrete lead that will snap my synapses into action.

So, what about Mnemonic? Now I have it. A man walks onto the stage, empty except for a small wooden chair, and starts talking to the audience. The house lights are still on. He rattles on about this show being a revival, how back then it would have been Simon McBurney, the director, standing before us. No-one is sure whether he’s a warmup, or the real thing; until we realise that he’s the real thing, whose gloriously zippy, zappy, high-speed monologue is seriously warming us up. Now, I remember this.

Other things swim back: the mysterious iceman, and another man in search of his lost lover, and particularly, the warm flood of ideas, which prompt both reflection and introspection. And what was a memory, of the play, becomes replaced by something new, fresh, equally intoxicating, which is already, as I write, becoming itself a memory.

Other things swim back: the mysterious iceman, and another man in search of his lost lover, and particularly, the warm flood of ideas, which prompt both reflection and introspection. And what was a memory, of the play, becomes replaced by something new, fresh, equally intoxicating, which is already, as I write, becoming itself a memory.

And that is very much the point. Or at least one of them. Mnemonic was conceived by McBurney but ‘devised’ by the original company in rehearsal; now it’s ‘reimagined’ by the new one (including some returning players), adding more recent events and, I assume, some refreshed intel on climate change. McBurney is still at the helm, if not on stage this time. It’s Complicité through and through, rich in ideas, demanding and exhilarating.

The actor in McBurney’s place is Khalid Abdalla (pictured above), a whirl of energy, charismatic and engaging as he navigates the dense introduction, which includes biological details about the workings of memory, alongside more metaphysical conjectures, ideas about migration as a result of climate change, (turbulence in the weather correlating with social upheaval) and a resonant metaphor: memory as a map, but an unstable one, taking us through our lives and those of others.

He also has time for some meta mischief, as when he wonders “Why don’t they put on normal plays anymore”, and leads that moment of audience participation, inviting everyone to don eye masks and caress a leaf that has been left on their seats, while imagining our parents and grandparents and great grandparents lining up behind us, row after row of ancestors casting back centuries.

The exercise speaks to perhaps the most powerful idea of all: memory as imagination, aa a creative act. The play is profound even in prologue; when Abdalla asks people to imagine themselves as children, their parents holding them by the hand, he surely unleashes a huge range of responses, from happy, idyllic, easily retrieved snapshots, to the blank spaces of the orphan or abused or simply unhappy.

The exercise speaks to perhaps the most powerful idea of all: memory as imagination, aa a creative act. The play is profound even in prologue; when Abdalla asks people to imagine themselves as children, their parents holding them by the hand, he surely unleashes a huge range of responses, from happy, idyllic, easily retrieved snapshots, to the blank spaces of the orphan or abused or simply unhappy.

Now Abdalla segues into a character, and the play into three stories that run concurrently and interactively. He is Omar, in the present, a man obsessed with the disappearance of his lover, Alice, nine months before; in another, we follow Alice, on a quest across Europe, in search of the father she never knew; and, in 1991, climate change leads to the emergence of a body in an Alpen glacier, and the ensuing scientific attempts to deduce who he was, and how he got there.

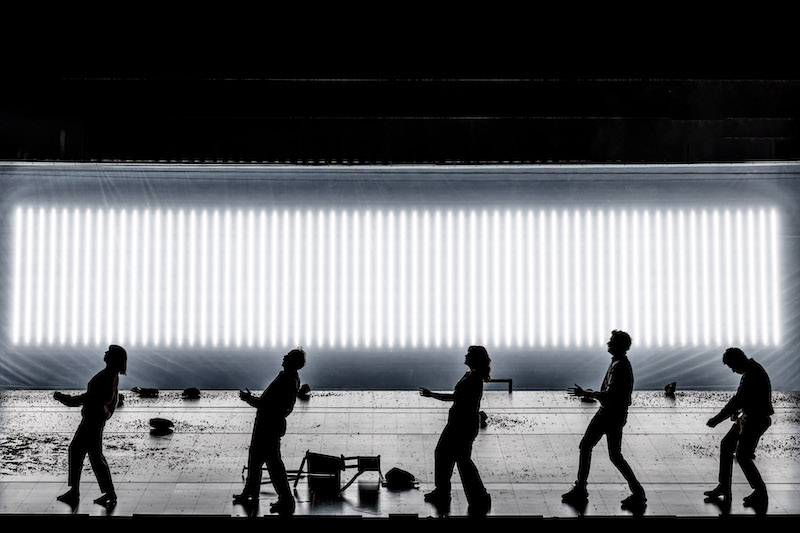

Mnemonic isn’t Complicité’s most visually dazzling or visceral production (it's a high bar), but it is constantly inventive, making panoramic use of the wide Olivier stage, and is at times quite ravishing (the ensemble, pictured above). Simple props – a bed, screens, the ubiquitous chair are employed to shift between bedrooms and morgues, lecture halls and hotel rooms, between decades and countries, while video projections evoke sandstorm, blizzard, static, speeding trains, and music and sound lend an hypnotic effect to the cross-cutting investigations before us.

Returning to the how, what and why of memory, objects frequently come into play as key instruments: the weapons, bits of bark and other objects found around the iceman’s body, even the contents of his stomach allow one interpretation after another; a highly comical episode sees a line up of talking heads, each with their own, very different characterisation of the iceman’s social role – trader, hunter, shaman. Meanwhile, a box of her father’s objects offers Alice clues to a heritage of which she was completely unaware.

And perhaps none of these people will find definitive answers. As one observes, “In the past, you will always be too late.”

The actors deftly switch between characters, most notably Abdalla between Omar and the iceman, the latter requiring frequent nudity as the 5,500-year-old man is prodded and probed by scientists and – could this be a masterful trick of lighting? – appearing to adopt a waxy, deathly patina when lying on a slab. Complicité regular Tim McMullan is as delightful as ever, especially as the man leading the attempt to piece together the iceman’s story; Eileen Walsh as Alice, Sara Slimani and Richard Katz (pictured above, with Walsh) are all outstanding.

The actors deftly switch between characters, most notably Abdalla between Omar and the iceman, the latter requiring frequent nudity as the 5,500-year-old man is prodded and probed by scientists and – could this be a masterful trick of lighting? – appearing to adopt a waxy, deathly patina when lying on a slab. Complicité regular Tim McMullan is as delightful as ever, especially as the man leading the attempt to piece together the iceman’s story; Eileen Walsh as Alice, Sara Slimani and Richard Katz (pictured above, with Walsh) are all outstanding.

One can feel here the keen presence of John Berger, McBurney’s great friend and collaborator, especially in the play’s investigation of migration (forced and unforced), of shared histories and personal stories, the see-saw between fragmentation and connection, all of which infuse Alice’s journey across Europe, which is updated to include war-torn Ukraine. There’s also a sense of Berger’s big heart, pulsing beneath the humour and open-mindedness. As well as being enormously thoughtful, it’s at times very funny.

Perhaps the most daring aspect of the play, one also shared with Berger’s work, is its willingness to focus on small, very distinct stories, while extrapolating expansively from them. It’s a leap that might not engage everyone; go with it, though, and it will linger for quite some time.

Add comment