What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank, Marylebone Theatre review - explosive play for today | reviews, news & interviews

What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank, Marylebone Theatre review - explosive play for today

What We Talk About When We Talk About Anne Frank, Marylebone Theatre review - explosive play for today

Nathan Englander probes a divide in modern Jewish identity; Patrick Marber directs

An incendiary play has opened at the Marylebone, the adventurous venue just off Baker Street. Bigger houses were apparently unwilling to stage it, fearing anti-Israeli protests. Their loss.

Nathan Englander has expanded his short story of the same title and brought it bang up to date. He was mid-writing when the October 7 attacks occurred, so rewrote the piece with Patrick Marber, factoring developments since into the dialogue. Any issue somebody might have with the current state of modern Judaism is examined here, at full volume, by two Jewish couples, one ultra-orthodox, one not so much. It’s acridly witty stuff, but deadly serious in intent, with a core of genuine pain. Think God of Carnage, but much louder and with weightier issues.

In one corner are Shoshana (Dorothea Myer-Bennett) and Yerucham (Simon Yadoo) from Jerusalem, who are visiting old friends in Florida. In their youth they were Laurel and Mark, but now Mark sports a prayer scarf, a big beard and a fedora, Laurel is in black with flat shoes and a wig. Not any wig but a sumptuous blonde number redolent of a 1940s movie star like Carole Lombard or Jean Harlow.

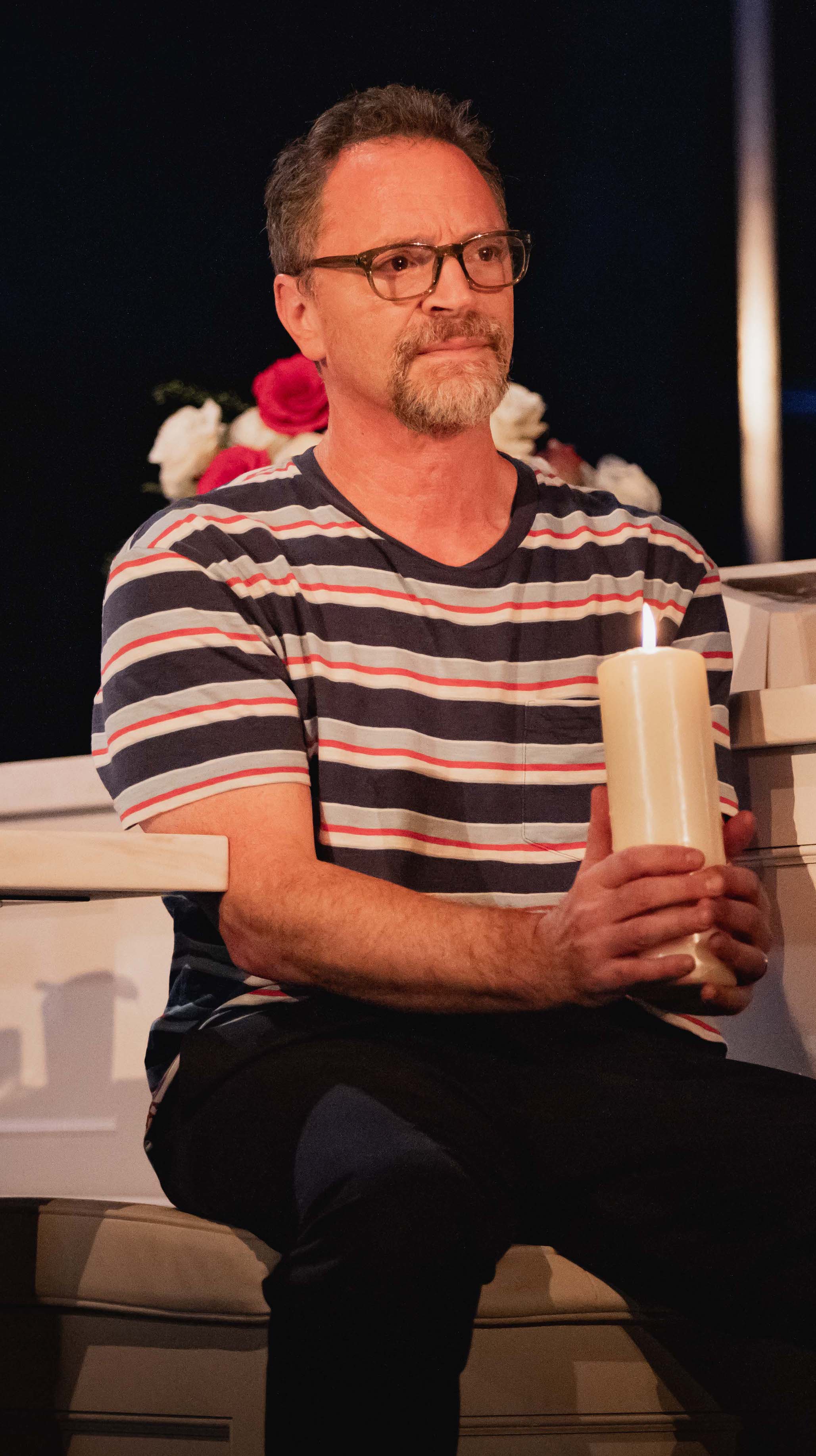

Their secular friends/opponents are Debbie (Caroline Catz) and Phil (West Wing alumnus Joshua Malina), a well heeled couple who live in an opulent modern palace of a home (the elegant design is by Anna Fleischle). Yerucham jokes, pointedly, that their kitchen alone could be used as a conference centre; he would fill it with loads of Jewish children, to repopulate the race. He and Shoshana have eight daughters; Debbie and Phil, a son called Trevor (Gabriel Howell, pictured below with Simon Yadoo), nicknamed Trevi, who is taking a year off college to “find himself”, as he puts it, sardonically. Shoshana and Yerucham clearly have no time for multi-culti liberalism, seeing it as “sugar-free, white bread” Judaism.

Trevor is the quasi-referee of the evening, announcing the scenes and their titles in a voice dripping with irony. It’s arguably the most fascinating role in the piece, which Howell delivers with panache: a young man with a world-weary soul, ferociously contemptuous of his parents’ generation and their failure to save the planet. HIs announcements distance the audience from the action, inclining us to see it as a process as well as a drama.

Trevor is the quasi-referee of the evening, announcing the scenes and their titles in a voice dripping with irony. It’s arguably the most fascinating role in the piece, which Howell delivers with panache: a young man with a world-weary soul, ferociously contemptuous of his parents’ generation and their failure to save the planet. HIs announcements distance the audience from the action, inclining us to see it as a process as well as a drama.

The few opening niceties over, the gloves quickly come off, as the ultra-orthodox couple spar verbally with the secular liberals in increasingly dismissive terms, querying what on earth they do do to show they are Jewish. Phil is anxious that Debbie does not follow the route of the friend of her youth, but Debbie has no wish to, feeling closed out by Shoshana’s new community. She tells a story that shows how far she has moved from any kind of orthodoxy, about an encounter with her rabbi's wife, who seemed to her to be dressed up as Frida Kahlo. Debbie was startled to realise she had overlooked that it was Purim, and the wife was dressed accordingly.

Which is the best country to live in for a Jew? No prizes for guessing who chooses what. Debbie cannot visit Israel, she tells Shoshana, because of what it is doing in Gaza and now Lebanon. And Phil, who snipes snidely and hilariously from the sidelines, wants nothing to do with Israel until it starts behaving less offensively and eases up on its apartheid policies – for which he gets a long diatribe from Shoshana about the Jews’ rights to the land, going back 4,000 years. She keeps focusing on the past, Phil on the future.

The Holocaust looms large, predictably, the event that shaped Debbie and Laurel’s schooling in lectures and film presentations. Footage of the camps provided Debbie with her first sighting of a penis, she wails. And she used to know the names of more camps than state capitals. Now a new holocaust is upon them, the ultra-orthodox wail back: intermarriage! It has cut the Jewish population in half and has even struck their own family.

The first half ends with the funniest scene in the piece, in which Trevor explains to Yerucham why he doesn’t identify as a Jew. He’s a Pastafarian, he tells the bewildered man, a religion whose god is a flying spaghetti monster and whose goal is to achieve equal rights for everybody on the planet. His church, he argues, is no more made up than any other.

The vodka bottle is being emptied fast, but things deteriorate even further when the couples find Trevor’s stash and smoke weed together, something Shoshana and Yerucham say le tout Jerusalem does all the time. Debbie and Phil aren’t used to its new potency and are soon wasted. They resort to ice cream. Between spoonfuls, Phil reveals his vision of an amusement park with a holocaust-themed food court, whose ice cream parlour will be titled “The Dairy of Anne Frank”. Shoshana is amused despite herself and offers the flavour “Pogrom and Raisin”. “It’s our tragedy to use any way we like!” Phil shouts.

The vodka bottle is being emptied fast, but things deteriorate even further when the couples find Trevor’s stash and smoke weed together, something Shoshana and Yerucham say le tout Jerusalem does all the time. Debbie and Phil aren’t used to its new potency and are soon wasted. They resort to ice cream. Between spoonfuls, Phil reveals his vision of an amusement park with a holocaust-themed food court, whose ice cream parlour will be titled “The Dairy of Anne Frank”. Shoshana is amused despite herself and offers the flavour “Pogrom and Raisin”. “It’s our tragedy to use any way we like!” Phil shouts.

Eventually, the powder keg blows up, and the verbal antagonism becomes physical, only interrupted by the return of a disgusted Trevor. And finally the Anne Frank Game is played, devised by Debbie in her youth: a ritual in which each participant holds a lit candle and one at a time asks the key question of the others: “The Nazis are coming – will you hide me?” All must answer with total truthfulness. It’s a chilling scene. But Englander follows it up with another that suspends the fighting and hints at a way forward.

It’s a welcome relief, much as a ceasefire of any kind is. The totally committed cast are an exhausting bunch, whipped along by Marber at a breakneck pace, their arguments sometimes drowning each other’s out. One yearns for more light and shade, even though their characters’ personalities don’t allow for that. There are no answers here, only clear opposing arguments. But the final tableau is worth the furore that has led up to it as they all, Trevor included, find a communality in dance. If only.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

Ragdoll, Jermyn Street Theatre review – compelling and emotionally truthful

Katherine Moar returns with a Patty Hearst-inspired follow up to her debut hit Farm Hall

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Troilus and Cressida, Globe Theatre review - a 'problem play' with added problems

Raucous and carnivalesque, but also ugly and incomprehensible

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Clarkston, Trafalgar Theatre review - two lads on a road to nowhere

Netflix star, Joe Locke, is the selling point of a production that needs one

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Ghost Stories, Peacock Theatre review - spirited staging but short on scares

Impressive spectacle saves an ageing show in an unsuitable venue

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Hamlet, National Theatre review - turning tragedy to comedy is no joke

Hiran Abeyeskera’s childlike prince falls flat in a mixed production

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Rohtko, Barbican review - postmodern meditation on fake and authentic art is less than the sum of its parts

Łukasz Twarkowski's production dazzles without illuminating

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Lee, Park Theatre review - Lee Krasner looks back on her life as an artist

Informative and interesting, the play's format limits its potential

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

Measure for Measure, RSC, Stratford review - 'problem play' has no problem with relevance

Shakespeare, in this adaptation, is at his most perceptive

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

The Importance of Being Earnest, Noël Coward Theatre review - dazzling and delightful queer fest

West End transfer of National Theatre hit stars Stephen Fry and Olly Alexander

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Get Down Tonight, Charing Cross Theatre review - glitz and hits from the 70s

If you love the songs of KC and the Sunshine Band, Please Do Go!

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

Punch, Apollo Theatre review - powerful play about the strength of redemption

James Graham's play transfixes the audience at every stage

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

The Billionaire Inside Your Head, Hampstead Theatre review - a map of a man with OCD

Will Lord's promising debut burdens a fine cast with too much dialogue

Add comment