I Never Tell Anybody Anything: The Life and Art of Edward Burra, BBC Four | reviews, news & interviews

I Never Tell Anybody Anything: The Life and Art of Edward Burra, BBC Four

I Never Tell Anybody Anything: The Life and Art of Edward Burra, BBC Four

One of Britain’s greatest but least-known 20th-century painters gets the Andrew Graham-Dixon treatment

What a relief: Andrew Graham-Dixon got the job of presenting this documentary on one of my favourite British 20th-century artists. If it had been Waldemar Januszczak (sometimes interesting but too gimmick-laden and shouty) or Matthew Collings (sometimes interesting but too fond of the catchy sweeping statement) I would have thought twice about tuning in. But Graham-Dixon understands that the art documentary is not about him, it’s about the artist.

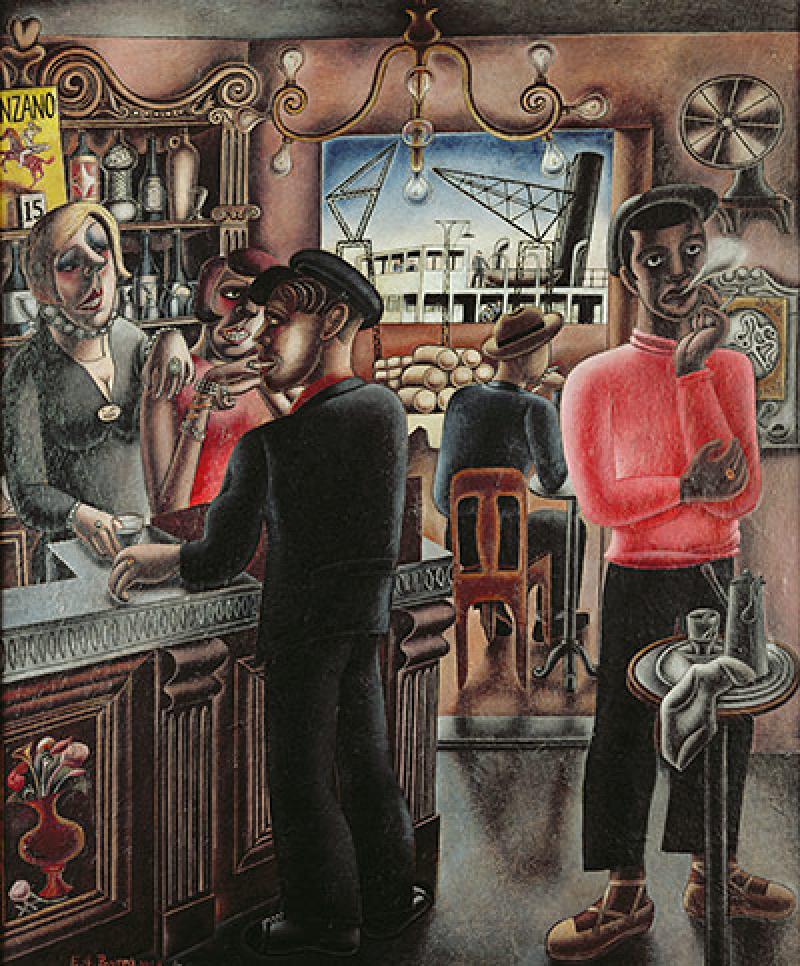

As this is telly and not an art history lecture, lucky old Graham-Dixon gets to follow in that artist’s footsteps to exotic, picturesque locations around the world. And so Burra was certainly the right subject to choose in this respect. Although his life began in leafily dull Rye in Sussex, and although he was horribly crippled from birth by rheumatoid arthritis, by the age of 15 he was off to art school in London. From there, over the next few decades, it was on to other early-20th-century arty hotspots such as Paris in the 1920s, Harlem in the 1930s and Spain during the Spanish Civil War. Initially, Burra was a garish caricaturist/satirist in the manner of Otto Dix or George Grosz (although artists as diverse as Seurat and Léger were in there somewhere, too) picking up on and exaggerating every telling detail of the eccentric, bustling crowds in the cafés and nightclubs he frequented. But as with his friend, Paul Nash, war eventually added gravitas and a new visceral power to his work.

Throughout his life Burra had been as hedonistic and adventurous as his physical disabilities would allow

That’s more or less the story. But, as always, Graham-Dixon attempts to both get inside the head of the artist and provide an intelligent - though not overtly intellectual - interpretation of his art. There was only one moment, towards the end of this stimulating hour, when his reading of something Burra said in a TV interview seemed a little too simplistic. To the question, “So what does it all mean then?” Burra, with a teasing twinkle in his eye, responded, “Nothing.” Graham-Dixon chose to ignore the twinkle and focus on the “nothing”, seeing it as a nihilistic response in the spirit of Samuel Beckett.

My more prosaic interpretation of that "nothing” was that Burra was simply tired of being asked what his art meant, rather than tired of life itself. After all, throughout his life he had been as hedonistic and adventurous as his physical disabilities would allow. Burra, smiling, had already said in the same interview, “I never tell anybody anything. So they just make it up.” Perhaps if the interviewer had changed tact and asked him about his favourite B-movies or trashy sci-fi novels, the old grump would have come to life. But instead Burra just kept up the habit of a lifetime, and left his vibrant, chattering, swinging paintings to do the talking for him.

But for Graham-Dixon this throwaway, teasing ”nothing” (in my view more in the spirit of John Lydon than Samuel Beckett) handily fed into his rather romantic view that Burra’s late landscapes of Cornwall and the Yorkshire Moors were his way of coming to terms with his own approaching death. I suspect that Burra would have been horrified by such a restrictive interpretation of these actually rather calm, meditative (rather than “morbid”, as Graham-Dixon has it) works in which, for the first time, Burra used watercolour as it should be used – in cool, translucent washes - rather than thickly applied it in an effort to achieve the luminosity of oil paint (a medium his arthritic hands prevented him from tackling due to the weight of the brushes).

But this small quibble is just a difference of opinion rather than a criticism. Programmes such as this excellent biographical documentary function as evidence that television is still the perfect medium for delivering the maximum amount of information, in the least amount of time, in the most stimulating fashion. And should you want to spend more time with the enigma that is Edward Burra, an exhibition of around 70 of his paintings has just opened at Pallant House in Chichester.

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Comments

An excellent review of a very