I interviewed Merle Haggard once and he’s a slippery old snake: dry, reserved and fiercely intelligent, with an ornery pride and an oft-used gift for riling people. I’m not sure we got to know him all that much better after Gandulf Hennig’s superb documentary Learning to Live with Myself, but it was a hell of a ride none the less. A man with hidden depths buried inside his hidden depths, Haggard said towards the end of the film that he had struggled his whole life to achieve his aim of being “self-contained, totally”. He wasn't about to go all therapy-speak on our asses now.

Filmed over three years, Hennig’s extensive portrait of The Hag was an admirably erudite affair, unrolling at an even pace and as spare and unshowy as the subject’s songs. Like so many driven artists, Haggard lost a parent early on. His family were dustbowl refugees from Oklahoma who had moved to California in the 1930s; aged nine he watched his father die in hospital and – in the days before grief counselling - he cut loose and ran. A childhood friend described him as “Huckleberry Finn”. His sister looked wearily amused at the romance of that description, preferring to call him a “constant problem”.

His second wife Bonnie was bridesmaid at his wedding to his third wife, which is proper country

Haggard turned to a life of vagrancy and crime, dropping down through the dregs of the penal system, from the brutalisation of correctional school to a fully paid up place at San Quentin prison by the time he was 19. He was imprisoned for “trying to break into a place that wasn’t even closed”. It was a rare shaft of humour in this sombre portrayal. Hennig made no attempt to glamorise this wayward, lonely life, and neither did Haggard. His stark, haunted memory of the rapes that took place in the prison yard was truly chilling and, although he was astute enough to realise that his image as a felon has done his career no harm, he has rarely played on it. He has, however, sung about it poignantly in death row songs like "Sing me Back Home".

Haggard travelled the traditional route to country enlightenment – Jimmie Rodgers, Bob Wills, Lefty Frizzel – but it was watching Johnny Cash play a 1958 prison show at San Quentin while he was an inmate that “turned a light on”. Paroled in 1960, along with Buck Owens he became instrumental in honing the Bakersfield Sound, a west coast antidote to the mawkish excesses of Nashville. Hard-edged, bluesy, hotter and “leaner”, in the words of interviewee Keith Richards, it had an immediacy that leapt from the speakers.

His dad “could sound like Jimmie Rodgers”, but Haggard’s wonderfully uncomplicated voice sounded like polished stone. He began to succeed on a national scale, putting together his band The Strangers (even his stage cohorts were branded by his feelings of alienation) and recording classics like "Mama’s Hungry Eyes", "Working Man Blues" and "Mama Tried". Pure, clean, forceful; above all, true. These were songs born from necessity, hewn from a life of “self-punishment and shame”.

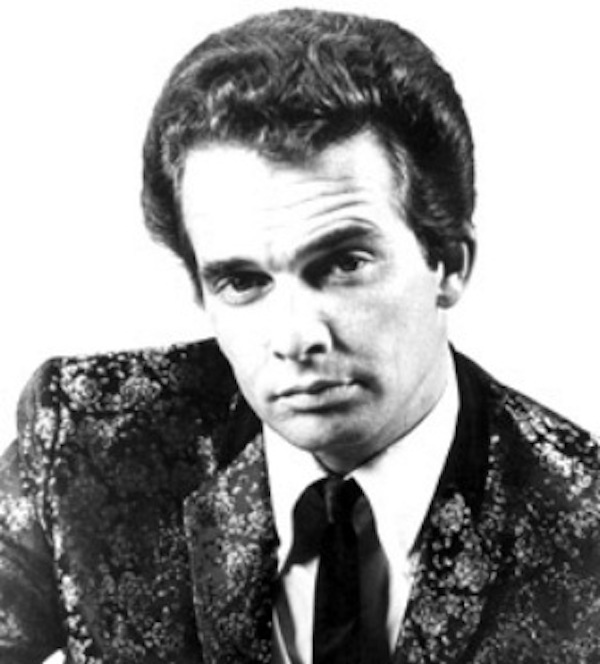

Hag's hot streak from 1966 to 1972 is virtually peerless. Handsome as Warren Beatty (pictured right), his refusal to go down the cinematic route – unlike contemporaries like Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson – probably cost him a larger profile and a few million bucks. He wasn’t interested. A shy, internalised man, his stern, mournful face told its own story. Like Nelson, he has sought refuge in endless touring, in the shrunken down safety of the bus (“my shark cage”) and the stage.

Hag's hot streak from 1966 to 1972 is virtually peerless. Handsome as Warren Beatty (pictured right), his refusal to go down the cinematic route – unlike contemporaries like Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson – probably cost him a larger profile and a few million bucks. He wasn’t interested. A shy, internalised man, his stern, mournful face told its own story. Like Nelson, he has sought refuge in endless touring, in the shrunken down safety of the bus (“my shark cage”) and the stage.

Aside from a generous scattering of live footage, archive material and ad hoc interviews with the man himself (though he hardly relaxed into the role of reality TV star), the highlights were observations from John Fogerty – “It’s not about being complicated, it’s about being memorable” – and Keith Richards, who owned up to his own shyness and vulnerability. Kris Kristofferson, on the other hand, was woefully underused and manager Fuzzy Owen didn’t quite live up to his name.

Apart from himself, Haggard’s primary subject is America – who makes the country tick, who keeps it rolling? His songs are for the workers on the assembly line, the soldiers, the farmers, the people who live between the railroads, telephone wires and broken down plots of land - and the people who got lost and left behind. It hasn’t always made for comfortable listening to liberal ears. An anarchist by nature who has deeply conservative feelings about his country, his 1969 smash hit "Okie From Muskogee" seemed like the ultimate redneck hippie-baiting anthem, although Haggard has claimed that it was written partially as a satirical joke. If so, the irony was lost on many hawks. Then again, he has also claimed the song was a tribute to his father’s generation, horrified at privileged drop-outs protesting against Vietnam, “a war they didn’t know any more about than I did”. Said the man who did time in San Quentin, “freedom is not free”, and in case anyone was confused we heard "The Fighting Side of Me", on which he sang: “If you’re running down our country, Hoss, you’re walking on the fighting side of me.”

The liquor and lovin’ were passed over relatively quickly, but there was a familiar subtext of overlooked children and a string of ex-wives. An early marriage to a girl with a drug problem was disastrous, while his third wife Leona (his second wife, Bonnie, was bridesmaid at their wedding, which is proper country) revealed that, “Merle only stays in love about five years”. His fourth wife Kelly said, “I think I can make him happy,” but seemed unsure.

She admitted it was unlikely that he has really learned to reconcile with his sadness and pain, but Haggard seems to have found some kind of peace with Kelly and his two youngest children. The 2000s have witnessed an artistic renaissance of sorts, alongside a brush with lung cancer which he called “a pretty tough deal”. At the age of 73 his voice isn't what it once was, but he’s still mixing it up. In 2005 he wrote "American First", a plea for the US to get out of Iraq which still managed to be unashamedly patriotic and pro-military. He talked of “the never dying fire” of the quest to write just one great song. He has, of course, written dozens of great songs, but he doesn’t seem to see it that way. You suspect that it’s the search that keeps him going.

Merle Haggard: 1937-2016

Overleaf: watch Merle Haggard performing "Okie From Muskogee"

Add comment