Camille Silvy may be the least recognised of all the great photographic innovators of the 19th century. After a decade of almost ceaseless technical innovation, and astonishing output as the society portrait-photographer of the 1860s, he abruptly closed his London studio, aged only 34, returned to France, and, after a brief stint in the garde mobile in the Franco-Prussian War, spent much of the rest of his life in and out of asylums. It has been suggested that the chemicals used in these pioneering decades of photography caused mental illness; but given his prodigious output - 17,000 sittings, and one million prints, in just nine years – one has to wonder if manic depression might not be at the root of both his staggering output and his later withdrawal.

Silvy was said to have given up a burgeoning diplomatic career for this new profession of photographer, but it must have been a career barely beginning to bud, for in 1858, aged only 22, he had already produced one of the works that won him renown, Valée de l’Huisne, a carefully staged landscape in which multiple images were merged, clouds from one negative transferred to another, the foreground "burnt in" afterwards, different exposures used, people carefully posed on the riverbank. Indeed, Silvy was more director than photographer, as the camera itself was "operated" by another. His follow-up, Trophées de la chasse of the same year, is also a remarkable simulacrum of a traditional still-life.

These images brought him recognition and praise in France, but the following year Silvy abruptly changed tack, decamping to London and setting up a studio in Bayswater in London that specialised in the newest vogue – the carte-de-visite, or portrait card. Silvy was a shrewd tactician, and he began by photographing actors, singers and other performers – there is a wonderfully light, bright image of the comedian Frederick Robson, halfway out of a door, his hat and elbow jauntily leaving the room. More traditional was his long photographic relationship with the opera star Adelina Patti (pictured above, in costume for the popular opera Martha, by Flotow). These images were used for promotional purposes by the sitters, but they were also collected by the public, thus promoting Silvy's name every time one was sold.

These images brought him recognition and praise in France, but the following year Silvy abruptly changed tack, decamping to London and setting up a studio in Bayswater in London that specialised in the newest vogue – the carte-de-visite, or portrait card. Silvy was a shrewd tactician, and he began by photographing actors, singers and other performers – there is a wonderfully light, bright image of the comedian Frederick Robson, halfway out of a door, his hat and elbow jauntily leaving the room. More traditional was his long photographic relationship with the opera star Adelina Patti (pictured above, in costume for the popular opera Martha, by Flotow). These images were used for promotional purposes by the sitters, but they were also collected by the public, thus promoting Silvy's name every time one was sold.

High society swiftly followed the stars, and Silvy was soon running a "factory" that would have put Andy Warhol’s similar art-workshop to shame: 40 people operated behind the scenes, while Silvy, always impeccably white-gloved, himself posed the sitters in his grand studio.

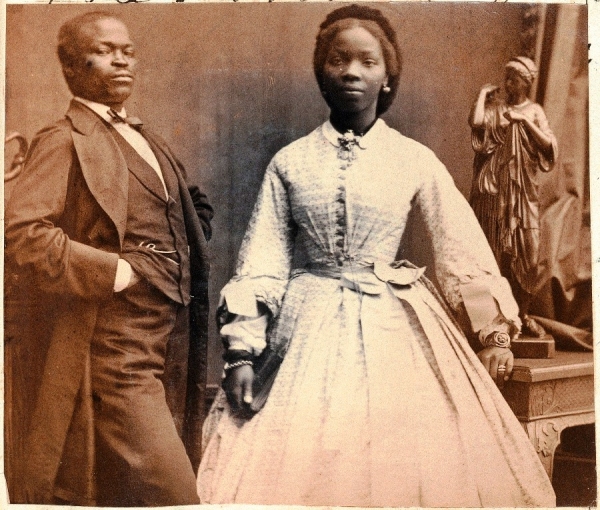

The sitters ranged from society couples (Silvy reached the apogee of society, photographing Prince Albert himself), to Queen Victoria’s black goddaughter, Sarah Forbes Bonetta (pictured right, with her husband), and even the today macabre-seeming practice of memorialising dead children in posthumous photographs. Silvy’s eye was remarkable, and what might in other hands have been routine poses, in his work come alive. The Misses Booth, two sisters, are posed with one facing the camera, the other beside her with her back turned. In a mirror between them, her face is captured and reflected back at the viewer, creating a triad of enlaced heads that would have pleased Van Dyck. The Misses Marjoribanks are less elaborately posed. Instead, their remarkable dresses speak for them, as the violent horizontal stripes across the crinolines are carefully arranged to create a single slashing line across the picture surface.

The sitters ranged from society couples (Silvy reached the apogee of society, photographing Prince Albert himself), to Queen Victoria’s black goddaughter, Sarah Forbes Bonetta (pictured right, with her husband), and even the today macabre-seeming practice of memorialising dead children in posthumous photographs. Silvy’s eye was remarkable, and what might in other hands have been routine poses, in his work come alive. The Misses Booth, two sisters, are posed with one facing the camera, the other beside her with her back turned. In a mirror between them, her face is captured and reflected back at the viewer, creating a triad of enlaced heads that would have pleased Van Dyck. The Misses Marjoribanks are less elaborately posed. Instead, their remarkable dresses speak for them, as the violent horizontal stripes across the crinolines are carefully arranged to create a single slashing line across the picture surface.

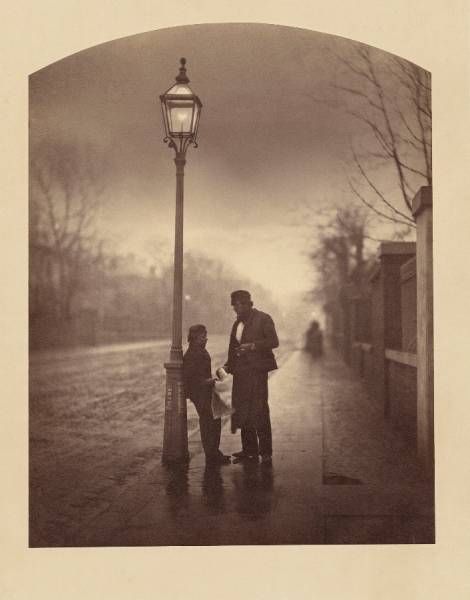

As well as these paying propositions, Silvy continued to experiment with the camera, promoting the reproduction of art, and creating some remarkable images of his own – Twilight (pictured below), photographed outside his Bayswater studio is, as with his early landscapes, in reality four different images combined. Yet it is this image, and its technique, that points up the oddity of the exhibition’s title. "Photographer of Modern Life" is Baudelaire’s description of the flâneur, that lounger-about-town who is both the recorder and the subject of modern life. Yet a flâneur is the very last thing that Silvy either was or recorded. The evanescent, fleeting, fugitive quality of modern life, the participant as artist, were what concerned Baudelaire, while Silvy harked back to an older tradition of craft and technique, of laboriously contrived 'reality', and of artist as observer.

Similarly, while the NPG has been admirably purist about showing original prints, the style of the period does work against a comfortable viewing experience today. Most of the images are tiny – the standard size for portraits is less than 90mm high – and the details that can be easily seen in larger reproductions, or even on screen, are almost invisible in the gallery. Thus Silvy’s art photography, which tends to be larger, is more accessible than the many dozens of portraits, which are almost better seen in Mark Haworth-Booth’s admirable catalogue that goes with the show.

Similarly, while the NPG has been admirably purist about showing original prints, the style of the period does work against a comfortable viewing experience today. Most of the images are tiny – the standard size for portraits is less than 90mm high – and the details that can be easily seen in larger reproductions, or even on screen, are almost invisible in the gallery. Thus Silvy’s art photography, which tends to be larger, is more accessible than the many dozens of portraits, which are almost better seen in Mark Haworth-Booth’s admirable catalogue that goes with the show.

Still, on the page or on the wall, it is good to have this extraordinary pioneer back with us, with this first exhibition in more than a century.

- Camille Silvy: Photographer of Modern Life 1834-1910 is at the National Portrait Gallery, London WC2 until 24 October

- Find Mark Haworth-Booth's work on Amazon

Add comment