Some exhibitions make you feel inspired, others perplexed. Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting at the National Portrait Gallery left me feeling battered and bruised – as if I’d been hit by a wrecking ball.

The show doesn’t start out that way. In the early 1940s, Freud spent several years perfecting his drawing technique. At first, he used a mapping pen, which produces clear, sharp lines perfect for detailed observation.

In a luminous self-portrait from 1947 intended as a book illustration, he uses a variety of marks to create the impression of a three-dimensional head. A shock of wiry hair frames his face while a fine stippling of ink dots chisels his features. Blank paper outlines the bridge of his nose and illuminates the whites of his eyes giving him a startled, wary look. Despite the surreal clarity of the image, the draughtsmanship is so exquisite that it makes you want to kiss his slightly pouting lips.

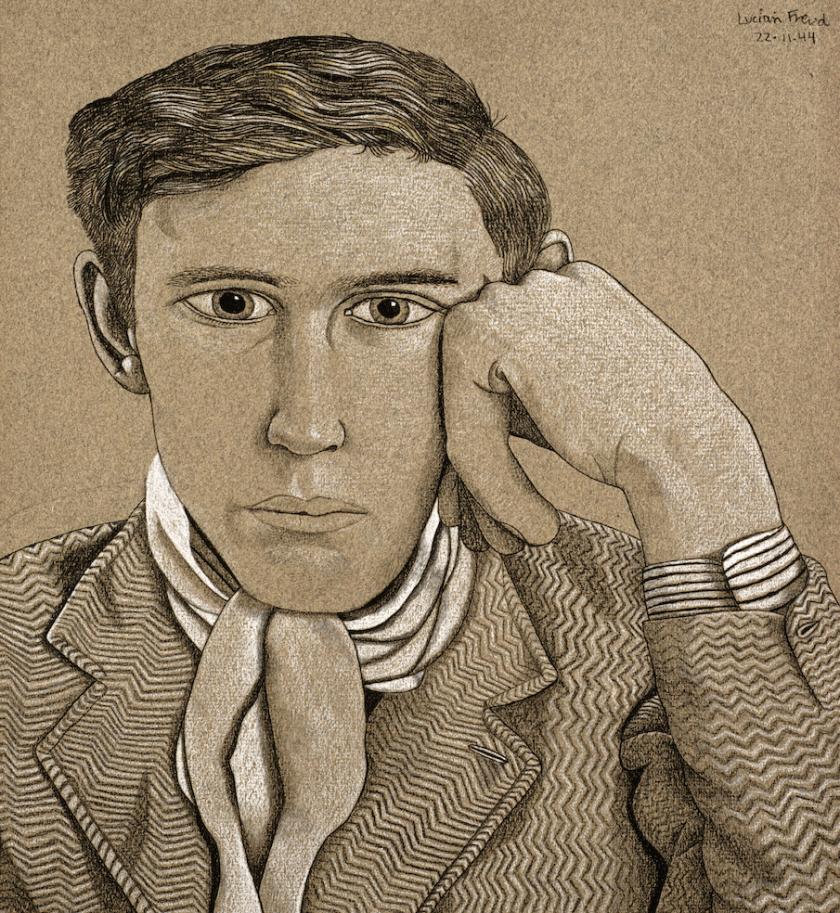

In his portrait of the artist John Craxton (main picture), Freud switches to conté crayon with white chalk for the highlights. Despite the insistent patterning of the jacket and the coal-black pupils of the man’s eyes, the shading and softer crayon lines make the image less disconcerting than the surgical precision of the ink drawings.

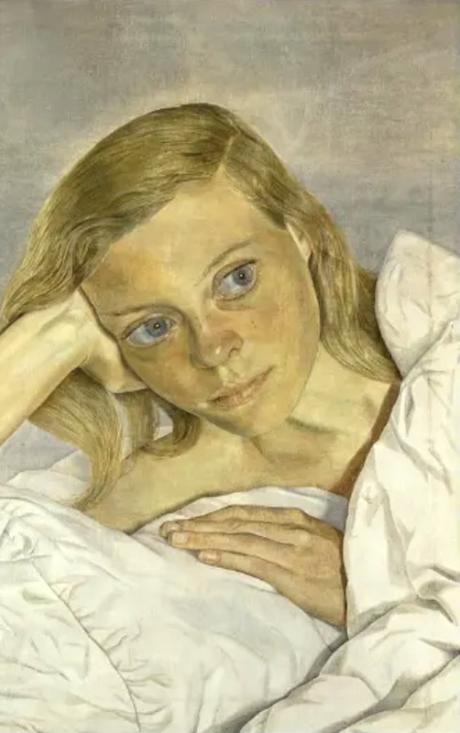

Freud’s early paintings reveal the same scalpel-sharp vision. Sitting close to his subjects he is able to see every nuance of skin tone and texture and to record them in minute detail with fine sable brushes. Girl in Bed 1952 (pictured right) is a portrait of his then wife, Caroline Blackwood. His unwavering gaze makes her seem horribly vulnerable, but it also creates a strong sense of her inner being. She resists his (and our) probing eyes by withdrawing into her own world. Despite the merciless scrutiny, she retains her dignity and sense of self.

“When I stood up I never sat down again” said Freud. Influenced by Francis Bacon, towards the end of the 1950s he dramatically changed his way of working. Concentrating on painting rather than drawing and switching from sable brushes to coarser hogs hair, he began working standing up. In a reversal of the age-old relationship between artist and sitter, he assumed a commanding position – looking down on his subjects.

It explains why, no matter what your views on royalty, his 2001 painting of the Queen seems so disrespectful. Whereas, traditionally, a monarch would have been portrayed looking down on his or her subjects from the elevated position of a throne or horse, the Queen is placed slightly beneath us, in close proximity. This makes the heavy diamond crown perched awkwardly atop her head look more ridiculous than regal. And there’s no flattery; Freud portrays her as a grumpy, pudgy faced matron with a grey chin suggestive of five o’clock shadow.

Those he respects are treated more kindly. His New York dealer, Bill Acquavella, fellow artist David Hockney (pictured above left), proprietor of The Wolseley brasserie Jeremy King and his mother are spared the gunmetal grey shadows that crisscross the faces of other sitters. Instead, warm skin tones and soft brown shadows lend them a healthy sense of resilience and integrity.

When he stands back to paint the whole figure, Freud’s gaze is no kinder; it may be less intrusive but feels colder and more clinical. His subjects become more like specimens splayed out for his examination and the nuanced lucidity of the early pictures is replaced by thick paint bodged into dense opacity as if he were trying to bully a likeness into being.

The sleepers are more able to withstand his dehumanising gaze. Double Portrait 1986 shows Susanna Chancellor lying in relaxed communion with her whippet Joshua, which makes her attitude of abandon seem chosen rather than imposed. With her eyes protected from the light by her arm, she withdraws into her own world and thus defends herself from intrusive eyes.

Nodding off in a leather armchair, the voluptuous Sue Tilley (Sleeping by the Lion Carpet 1996) seems at ease despite her nakedness. It’s as though her mountainous flesh were a vast blanket, a pearly carapace that protects her innermost being from prying eyes. Only the surface is revealed.

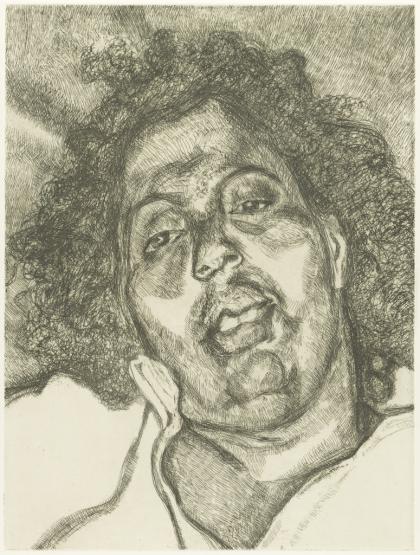

Freud returned to etching in 1982, replacing brushstrokes with sweeping lines, dark furrows and heavy cross-hatching that, printed black, make his sitters look battered, pulpy and gaunt. Lord Goodman (1987) comes across as a deranged thug while Marilyn Gurland (Solicitor’s Head, 2003, pictured above right) looks battered and bruised – like a victim of domestic abuse. It’s significant that Freud rarely named his subjects, preferring to treat them as anonymous examples of the species. "I am inclined to think of humans.. if they're dressed, as animals dressed up", he once said.

The artist frequently subjected himself to his own unwavering gaze, but because we see him at eye level or above, he appears heroic even when naked – more like a titan facing down the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune than a mere mortal overwhelmed by life. Painted in 2002 when he was 80, his final self-portrait is tilted Reflection in reference to the mirror he used to see himself, but also to the solitary introspection suggested by his downcast eyes. It’s as though the inner world he so often denied his sitters is at last being acknowledged. I wonder what his grandfather, Sigmund Freud would have made of that.

- Lucian Freud: Drawing into Painting at the National Portrait Gallery until 4 May

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment