One of the first images in the Royal Academy’s splendid exhibition is an ink drawing made in 1949 for a book on Greek myths. Freud casts himself as Actaeon who, according to the myth, accidentally came across Diana, goddess of the hunt, bathing naked. In punishment for the transgression, she turned him into a stag to be hunted down and torn apart by her hounds.

We see Actaeon peering through some leaves, antlers already sprouting from his head. The look of surprise and apprehension in his eyes indicates the dawning realisation that he has seen too much. The image is like an emblem of Freud’s future career as an artist – he was to spend countless hours scrutinising naked women in a way that feels like trespass. The most famous is Sue Tilley, the benefits supervisor who exposed her mountainous body to his gaze in the 1990s; looking at his paintings of her and other women I have always felt that his merciless exploration of every nook and cranny was an attempt to penetrate their very being.

We see Actaeon peering through some leaves, antlers already sprouting from his head. The look of surprise and apprehension in his eyes indicates the dawning realisation that he has seen too much. The image is like an emblem of Freud’s future career as an artist – he was to spend countless hours scrutinising naked women in a way that feels like trespass. The most famous is Sue Tilley, the benefits supervisor who exposed her mountainous body to his gaze in the 1990s; looking at his paintings of her and other women I have always felt that his merciless exploration of every nook and cranny was an attempt to penetrate their very being.

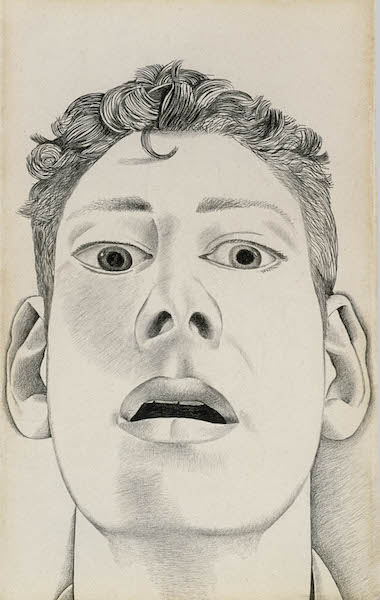

“The only way I could work properly was by using the absolute maximum of observation and concentration that I could muster”, Freud has said by way of explanation. And in the early years those powers of observation were mainly directed at himself. Startled Man: Self-portrait, 1948 (Pictured above right), is a pencil drawing whose sharp focus and clarity of line creates amazing intensity. We see his face from below; looking up into his open mouth, nostrils and ears and gazing at the dark pupils of his eyes makes one unusually aware of the orifices through which information flows to the brain. Like someone high on acid, the 26 year old artist looks hyper alert – transfixed by what he sees, hears, smells and tastes.

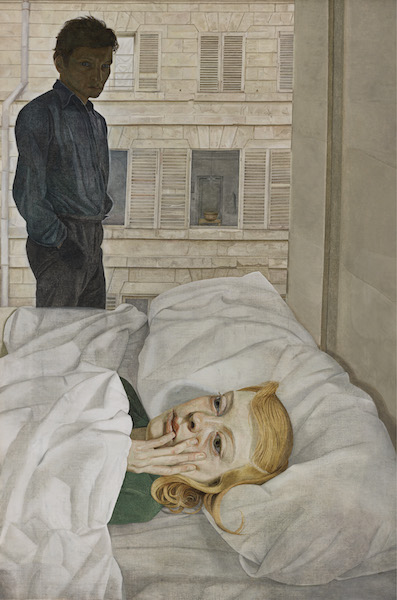

With its sharp-focused hyper-realism and exaggerated emphasis on people’s eyes, the early work repeatedly highlights the act of looking. In Hotel Bedroom, 1954, (pictured below left) we see Freud’s then wife, Lady Caroline Blackwood lying in bed looking pale and ill. We are watching her, and so is he; the artist appears as a dark silhouette looking at her from the other side of the bed. He is scrutinising her both from inside the picture and outside, at the easel. And her response is to withdraw, traumatised by the ubiquity of his gaze.

This was the last painting Freud made sitting down and switching from fine sable to hog’s hair brushes, which could handle much thicker paint, allowed him to develop a much freer, less linear style. The clarity of the early work gradually gives way to a more painterly approach, yet emphasis on painting as an act of voyeurism still remains paramount. By inserting himself into his portraits of other people, Freud continually reminds us of the triangular relationship between artist, sitter and viewer.

In Flora with Blue Toenails, 2001, the shadow of his head falls across the sheet on which she lies naked, creating an awareness of him as a looming, sinister presence. In another picture, his legs appear above the sofa on which the model lies exposed, thereby increasing the sense of her vulnerability. Although Freud is only playing a bit part, this still feels like an act of dominance; it’s as if he is laying claim both to the women and their images.

In Flora with Blue Toenails, 2001, the shadow of his head falls across the sheet on which she lies naked, creating an awareness of him as a looming, sinister presence. In another picture, his legs appear above the sofa on which the model lies exposed, thereby increasing the sense of her vulnerability. Although Freud is only playing a bit part, this still feels like an act of dominance; it’s as if he is laying claim both to the women and their images.

The gender politics is interesting. Freud occasionally makes an appearance in paintings of men, but in a subordinate role. The two little self-portraits propped against the skirting boards in Two Irishmen in W11, 1985, are like modest footnotes, one for each sitter. There he is again in Freddy Standing, 2001. Whereas his naked women tend to be lying down, prone and vulnerable, his naked son dominates the corner of the studio where he stands tall and in command. The artist’s reflection can be seen in the window; but, dabbing away at the canvas, he is dwarfed by the virile presence of his offspring.

When Freud turns his gaze fully on himself, though, the outcome is one of empowerment. In Reflection (Self-portrait), 1985, his head and shoulders become a potent sculptural presence. The rivulets of shadow that criss cross his face and neck like camouflage give him a striking military demeanour. The last room of late self-portraits comes as a revelation, then. In 1993, aged 71 (Pictured below right), Freud painted a full-length portrait of himself wearing nothing but a pair of boots with the laces removed, as though he were an inmate in an asylum at risk of self-harming. “Now”, he said, “the very least I can do is paint myself naked.” At last, that scalpel-sharp eye has been turned towards its owner; and the resulting picture is one of his finest. Standing alone in the studio, palette in one hand and palette knife in the other, Freud presents himself to us without pretension or pretence. The easel is out of frame, so he seems to be dabbing at empty space; this vacuum suggests a degree of modesty about his own achievements and the importance of painting in general. “It is then … towards the completion of the work”, he once said, “that the painter realises that it is only a picture he is painting. Until then he had almost dared to hope that the picture might spring to life.”

The accumulation of thick paint on the face and genitals reveals the struggle he had to render these difficult areas convincingly. In Self-portrait, 1991, the paintwork has become so densely scumbled that the entire face appears scabby and leprous. It’s as if the flesh were disintegrating before one’s eyes; meanwhile the penetrating gaze has begun to waver and the eyes to dim. And as the sharpness and clarity of the artists’s vision fades with age, the dynamics between viewer and viewed also shifts. The bravado of that dominating stare is replaced by introspection, humility and an acknowledgement of diminishing powers. Surprising strength comes from the acceptance of one’s own vulnerability, though. These last pictures are by far the most affecting and poignant of all Freud’s works.

The accumulation of thick paint on the face and genitals reveals the struggle he had to render these difficult areas convincingly. In Self-portrait, 1991, the paintwork has become so densely scumbled that the entire face appears scabby and leprous. It’s as if the flesh were disintegrating before one’s eyes; meanwhile the penetrating gaze has begun to waver and the eyes to dim. And as the sharpness and clarity of the artists’s vision fades with age, the dynamics between viewer and viewed also shifts. The bravado of that dominating stare is replaced by introspection, humility and an acknowledgement of diminishing powers. Surprising strength comes from the acceptance of one’s own vulnerability, though. These last pictures are by far the most affecting and poignant of all Freud’s works.

reviews, news & interviews

the future of arts journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more visual arts

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Three artists explore global concerns in rural West Sussex

The rise and rise of an artist

It pays to delay; how to be a great painter at 91

A painter’s journey in the wrong direction

Seascapes in which everything is stilled into a sense of harmony

Five of the best of the year's shows

Photography used to question who and what is worth recording

Light as a physical presence

At last, a UK festival that takes photography seriously

Add comment