Manchester was once known as Cottonopolis, since the city was once at the centre of the vast global industry reponsible for its growth and prosperity.The Whitworth Art Gallery, which is part of Manchester University, has in its collection a wealth of textiles, providing not just a colourful history of local cotton manufacture, but tracing the trade’s international links. However, this exhibition is less historical overview, more discursive exploration of the cotton trade’s social impact.

The exhibition provokes questions surrounding the ethical production of what had become, by the end of the 19th century, the most ubiquitous natural fibre in the world. In 1790 cotton accounted for just 4 per cent of all clothing in Europe and America; by 1890 that figure had risen to 73 per cent. The invention of new technologies in weaving and spinning heralded England’s industrial revolution. But such a rise, inevitably, came at a human cost. This cost is explored in this exhibition - though, with the involvement of local school groups, it can at times feel just a little too much like an extended school project.

Cottonopolis is one work by teenagers who visited Ahmedabad, India’s current cotton capital. With artist Sally Olding, the school group produced a printed woodblock model of a congested imaginary city that combines Manchester and the Gujarat capital. A nearby video shows one of the group observe that, unlike the local Ahmedabad population, the English seem not to be at all proud of their own heritage, nor particularly interested in their history. The emphasis on a global context illuminates this exhibition, but as one wanders through the displays the remark resonates: one might certainly have enjoyed more focus on the cotton industry as the catalyst for modern Britain.

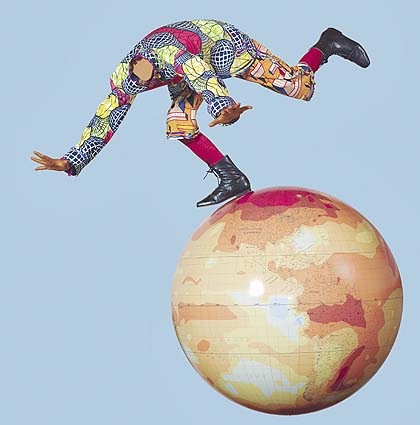

That said, there are some very enjoyable highlights among the works of the contemporary artists who have been specially commissioned for this exhibition. These showcase artists who not only use textiles in their work, but who have something to say about the polical and social ramifications of its use, though Yinka Shonibare’s presence, with his trademark batik fabric, is perhaps a little too predictable. Here we see an atlas globe (pictured right: Boy on Globe 4, 2011) suspended from a ceiling on which a headless figure in 18th-century dress appears to be losing his balance.

That said, there are some very enjoyable highlights among the works of the contemporary artists who have been specially commissioned for this exhibition. These showcase artists who not only use textiles in their work, but who have something to say about the polical and social ramifications of its use, though Yinka Shonibare’s presence, with his trademark batik fabric, is perhaps a little too predictable. Here we see an atlas globe (pictured right: Boy on Globe 4, 2011) suspended from a ceiling on which a headless figure in 18th-century dress appears to be losing his balance.

As most who are familiar with this artist’s work know, Shonibare uses brightly patterned prints which look native to West Africa but are manufactured in Holland – where they were originally produced – and bought by him in Brixton Market. The theme of cultural hybridity underpins this exhibition.

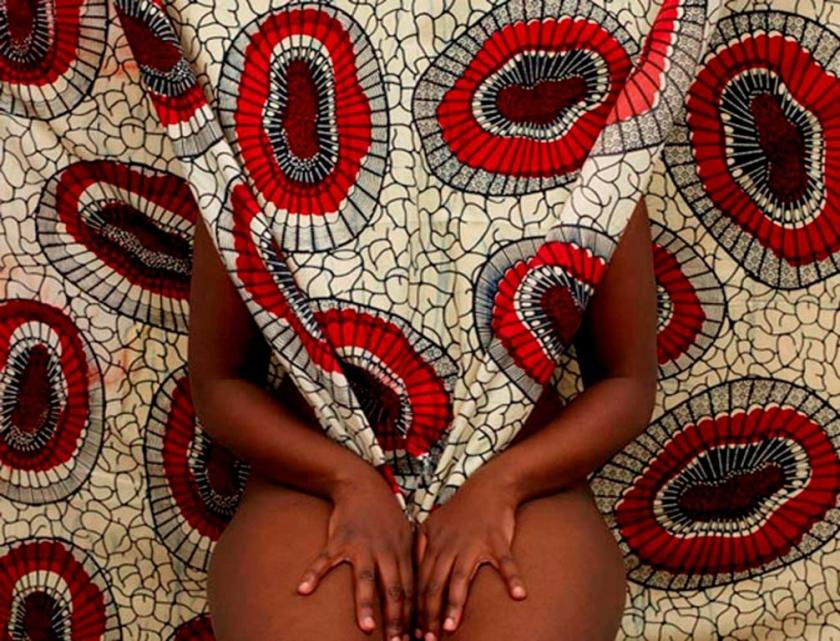

One captivating work belongs to British-Malian artist Grace Ndiritu. Her video work is a performance piece called Still Life (main picture) in which she uses sheets of beautifully printed West African cotton to conceal and reveal her body in a series of sinuous movements. Equally seductive is Liz Rideal’s Drop Sari (pictured above), a film that’s projected onto the exterior of the building at night. Inside, the film can be seen on a large screen as the centrepiece of the exhibition: inspired by 19th century Indian sample books, it shows a sequence of close-up shots of billowing drapery, removed from any context. Elsewhere, Lubaina Himid’s Kangas – pieces of printed fabric traditionally worn in West Africa but here based on designs the artist found in the Whitworth’s textile collection – have the appearance of functional items of clothing.

One non-contemporary highlight is the beautifully preserved 18th century handpainted cotton tent which once belonged to Tipu Shahib, the sultan of Mysore. The fabric is arranged across one wall, its repeated pattern of bright red flowers unfaded by time. Before Britain’s industrial revolution, India was the foremost producer of luxury textiles and cotton is inevitably tied up with India’s colonial past. Much later, cotton was to play a highly symbolic role in the struggle for independence. In the 1920s, Gandhi called for the boycott of British textiles and urged people to buy Indian-produced khadi (hand-spun, hand-woven cloth). A spinning wheel still adorns the Indian national flag.

Cotton has been hugely significant commodity in shaping the world as we know it today. Perhaps this exhibition might have given even more room to that fascinating history, rather than to some of the more interactive displays that can been seen alongside the artworks. Personally, I doubt if anyone will be game for trying on, in the dressing room provided, the “upcycled” clothes that are hanging in one section of the exhibition.

- Cotton: Global Threads at Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, until 13 May

Add comment