Edvard Munch strikes a heroic pose. Buck naked, he’s pointing a sword at the sky – or perhaps that’s just a stick he’s picked up in the garden, where he’s surrounded by dense greenery as he stands with his arm raised in a taut diagonal. Perhaps he is dreaming of Gram, the Norse Excalibur, and himself as Sigurd.

Another photographic self-portrait, taken four years later in 1907, shows the Norwegian artist posing on the beach. This time his modesty is preserved by a loincloth and on this occasion he is holding a palette and brush. But this is not quite the archetypal self-portrait of the artist. He points the brush at a shadow in front of him rather than the huge canvas behind, and our eyes are drawn not to the multiple standing, life-sized self-portraits, but rather to a character who could be Munch’s alter-ego: a man in heroic mid-stride, like the figure of Zeus, or, from the way he’s positioned himself, perhaps like Boccioni’s Futurist warrior – though, unlike Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, this figure seems to be reaching back to the mythological past rather than marching towards a mechanistic future.

There are lots of photographs at Tate Modern’s revisionist exhibition, and these mainly feature the artist’s self-portraits (apart from his dog he appears little interested in others). The Modern Eye seeks to establish Munch as a modern artist with modern concerns, the contemporary of figures such as Kandinsky and Mondrian, rather than of Toulouse-Lautrec and the artists of the fin de siècle – though all four painters were, in fact, born within a decade of one another. Deploying his interest in photography and film, and emphasising his engagement with their experimental potential, it’s a reasonably persuasive thesis. We find ghostly blurrings and double exposures mostly, and also recurring images where he holds the camera at arms length instead of using a tripod, so that his head in profile appears almost abutting the picture surface. Even in our age of the phone camera, these images still manage to look distinctly odd.

There are lots of photographs at Tate Modern’s revisionist exhibition, and these mainly feature the artist’s self-portraits (apart from his dog he appears little interested in others). The Modern Eye seeks to establish Munch as a modern artist with modern concerns, the contemporary of figures such as Kandinsky and Mondrian, rather than of Toulouse-Lautrec and the artists of the fin de siècle – though all four painters were, in fact, born within a decade of one another. Deploying his interest in photography and film, and emphasising his engagement with their experimental potential, it’s a reasonably persuasive thesis. We find ghostly blurrings and double exposures mostly, and also recurring images where he holds the camera at arms length instead of using a tripod, so that his head in profile appears almost abutting the picture surface. Even in our age of the phone camera, these images still manage to look distinctly odd.

Still, we also can’t get away from the fact that all of Munch’s iconic images were originally conceived in the last decade of the 19th century, in his series of canvases which he called The Frieze of Life. These he returned to again and again over the next few decades, and they place him resolutely in the Symbolist camp rather than the modern one.

Among his Frieze of Life paintings we find Puberty, Jealousy, The Kiss, Vampire, The Sick Child, Anxiety, The Bridge, Ashes, and The Scream. No Screams are present in this exhibition but, though one notes its absence, one really doesn’t miss this defining image of cartoonish angst.

Others in the series are present, and shown in duplicate versions, including two large canvases of The Sick Child, one painted in 1907 (pictured left), the other in 1925. The later work is looser and paler, losing something of the former’s intensity, though compositionally nothing significant has changed. In both, a pale, red-headed young girl sits up in bed, her frail body resting against a huge plump pillow, her exhausted face turned towards a bowed female figure who clasps the child’s arm in either anguish or prayer.

Others in the series are present, and shown in duplicate versions, including two large canvases of The Sick Child, one painted in 1907 (pictured left), the other in 1925. The later work is looser and paler, losing something of the former’s intensity, though compositionally nothing significant has changed. In both, a pale, red-headed young girl sits up in bed, her frail body resting against a huge plump pillow, her exhausted face turned towards a bowed female figure who clasps the child’s arm in either anguish or prayer.

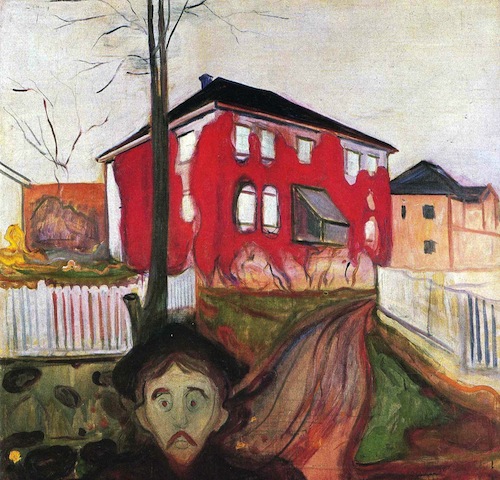

Munch lost his own sister to consumption when he was 13 and she just 15, and death and sickness have this exhibition in its grip. And like many of Munch's paintings we find that the juxtaposition here of reds and dark, mossy greens, adds a sickly and oppressive note, though one of Munch’s favourite optical tricks, dizzying perspectival exaggeration, is not employed for this claustrophobic scene. Instead it’s used most strikingly in The Girls on a Bridge, and in the arrestingly creepy Red Virginia Creeper, 1898-1900 (pictured overleaf).

Here a bemused, goggle-eyed face appears at the bottom of the picture frame, and every feature of this strange figure's head, from his black cap to the upside-down V of his moustache and the curved diagonal of his eyebrows, appears to be drooping in a kind of petrified mask. Behind him we find a sharply narrowing road, painted with characteristic striations of sickly, clashing hues, leading abruptly to a big red house with white windows. The white paint appears to bleed onto the red surface of the house, and there are what appear to be white tombstones clustered around the front of this deserted but decidedly bourgeois dwelling.

Here a bemused, goggle-eyed face appears at the bottom of the picture frame, and every feature of this strange figure's head, from his black cap to the upside-down V of his moustache and the curved diagonal of his eyebrows, appears to be drooping in a kind of petrified mask. Behind him we find a sharply narrowing road, painted with characteristic striations of sickly, clashing hues, leading abruptly to a big red house with white windows. The white paint appears to bleed onto the red surface of the house, and there are what appear to be white tombstones clustered around the front of this deserted but decidedly bourgeois dwelling.

Munch reworked these images because there was a market demand for them. At the time it was fairly common practice, yet Munch was uncomfortable with the notion of a “picture factory”. “I build one painting on the last,” he said, in what one may feel is a defensive statement. But there also seems little doubt that obsession must have driven him on, so absorbed are the paintings with enduring themes of human suffering and diseased desire.

Munch reworked these images because there was a market demand for them. At the time it was fairly common practice, yet Munch was uncomfortable with the notion of a “picture factory”. “I build one painting on the last,” he said, in what one may feel is a defensive statement. But there also seems little doubt that obsession must have driven him on, so absorbed are the paintings with enduring themes of human suffering and diseased desire.

The emphasis on his more mature paintings, however, feels right. Three quarters of Munch’s output was painted after 1900 (he died aged 71 in 1944, the same year as Mondrian) and here you’ll find a fine and intriguing selection, beautifully hung, and far more satisfying than the Royal Academy’s Munch exhibition of 2005.

Munch was a productive and variable artist, and we find some of his choicest later works here. And in this context, the photographs are fascinating because Munch seems to have used the medium as a way of defining his image; as we see he had an unquestionable gift for theatrical self-mythology. What’s more, the theatre absorbed him greatly, and at one point he collaborated with celebrated director Max Reinhardt on a Berlin production of Ibsen’s Ghost, providing sketches for the furniture and décor.

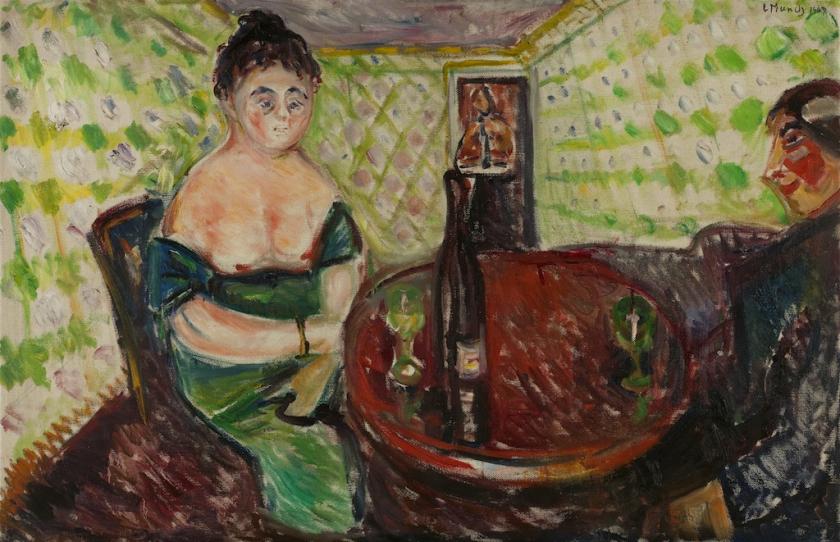

This sense of theatricality serves him well in the Weeping Woman series, 1907-9 (pictured left), with its distinctly stagey, Sickert-like domestic space. Sickert’s Camden Murder Series was painted at around the same time, so it’s more likely that Degas’s domestic psycho-dramas are the key influence here, rather than the British artist. But there’s a similarity nonetheless that’s uncanny, even though there are obvious differences: here the woman appears alone and she is standing rather than appearing as an inert presence in her bed. These paintings are one of the highlights of this exhibition.

This sense of theatricality serves him well in the Weeping Woman series, 1907-9 (pictured left), with its distinctly stagey, Sickert-like domestic space. Sickert’s Camden Murder Series was painted at around the same time, so it’s more likely that Degas’s domestic psycho-dramas are the key influence here, rather than the British artist. But there’s a similarity nonetheless that’s uncanny, even though there are obvious differences: here the woman appears alone and she is standing rather than appearing as an inert presence in her bed. These paintings are one of the highlights of this exhibition.

One other remarkable highlight is Self-Portrait with Spanish Flu, 1919 (pictured above right), a huge painting that possesses something of the monumentality of a Velázquez pope. Munch, berobed and open-mouthed, sits in his chair, a pallid, sickly ghost, white knuckles, clutching at his blanket. He stares at us as if in shock. It’s an unforgettable painting.

- Edvard Munch: The Modern Eye at Tate Modern until 14 October

Add comment