Franz West must have been a right pain in the arse. He left school at 16, went travelling, got hooked on hard drugs which he later replaced with heavy drinking, got into endless arguments and fights, was obsessed with sex and, above all, wanted to be an artist but hadn’t been to art school. His life reads like a bad novel or Hollywood’s idea of the tortured genius struggling to make his mark in a world indifferent to his talents. That world was 1970s Vienna, dominated by the Viennese Aktionists whose performances involved a lot of blood, guts and existential angst and were intended to shock.

But West also made friends, especially among younger artists with whom he loved to collaborate. Sarah Lucas was one and, for this retrospective, she has designed the dividing walls and some of the plinths supporting West’s lumpen sculptures. Her MDF and concrete interventions are extremely elegant, but they also serve to tame the scruffy anarchy of the work.

West’s early drawings are cartoonish jokes about pissing, voyeurism, sex, and combinations of the three. They wouldn’t have got him anywhere if, in 1974, he hadn’t started making sculptures for people to interact with. Resembling prezels, elongated sausages or cack-handed implements, these plaster and papier maché Adaptives (Passstücke) are now too fragile to handle, but you are invited to try out some more robust ones made from metal. Since they are too awkward and heavy to handle with ease, the idea was always more interesting than the actuality,

West’s early drawings are cartoonish jokes about pissing, voyeurism, sex, and combinations of the three. They wouldn’t have got him anywhere if, in 1974, he hadn’t started making sculptures for people to interact with. Resembling prezels, elongated sausages or cack-handed implements, these plaster and papier maché Adaptives (Passstücke) are now too fragile to handle, but you are invited to try out some more robust ones made from metal. Since they are too awkward and heavy to handle with ease, the idea was always more interesting than the actuality,

Next come the Legitimate Sculptures which sit on plinths like “proper” art and are not meant to be touched. Misshapen plaster and papier maché lumps daubed with random splodges of paint, they are displayed on Lucas’s neat plinths. Vaguely resembling heads, they are endearingly idiotic. Things really took off, though, when West began incorporating items he had lying around the studio – an old bucket or broom, paint brushes, coat hangers, empty paint tins, cardboard tubes and beer bottles.

Deutscher Humor, (German Humour) 1987 is an old broom shoved into an orifice in a contorted pile of papier maché enveloped in plaster, which says something about the Austrian view of German jokes. Painted livid green, Trunkenes Gebot, 1988 leans against the wall like a stumbling drunk. It resembles a broken leg ineptly encased in plaster, while protruding from the top like a thirsty mouth is the rim of a beer bottle. West was drinking heavily at the time but didn’t want to throw away the bottles and so they were “sublimated into art”. He even made a sculpture from his childhood bed, which he reconfigured in a shape resembling a shallow bath or the wonky prow of a ship and covered in aluminium foil.

How, though, to display these deliberately crude and anarchic objects? Some rest on feet made from reinforcing rods, others have plastic lids as pedestals. Many are plonked on the floor and propped up with anything from an old paint can to a hoover nozzle or a fistful of bubblewrap (pictured above right: Moses's Left Horn, 2004). Elsewhere cheap tables, old shelving, tacky cupboards and even antique furniture are pressed into service as plinths. Some sculptures stand on plinths painted by West’s friend Herbert Brandl in shiny black, syrupy chocolate brown, a rather nauseating salmon pink and off-white. To liven up the discourse, the pair also reversed the relationship by precariously balancing a plinth atop a sculpture.

How, though, to display these deliberately crude and anarchic objects? Some rest on feet made from reinforcing rods, others have plastic lids as pedestals. Many are plonked on the floor and propped up with anything from an old paint can to a hoover nozzle or a fistful of bubblewrap (pictured above right: Moses's Left Horn, 2004). Elsewhere cheap tables, old shelving, tacky cupboards and even antique furniture are pressed into service as plinths. Some sculptures stand on plinths painted by West’s friend Herbert Brandl in shiny black, syrupy chocolate brown, a rather nauseating salmon pink and off-white. To liven up the discourse, the pair also reversed the relationship by precariously balancing a plinth atop a sculpture.

West relished subversive interactions like these, which take the craft out of art and undermine any distinctions between art and design. He wanted his work to feel vital, alive; viewers were even invited to dump rubbish inside the gaping mouths of a group of huge, eyeless heads (pictured above: Lemur Heads, 1992) to give them bad breath, while Pleonasme, 1999 has a bucket rammed into its open mouth. Increasingly, he saw the display as integral to the work and began creating room-like environments furnished with metal chairs. An element of tongue-in-cheek humour pervades, since the chairs are uncomfortable and the art does not invite close study.

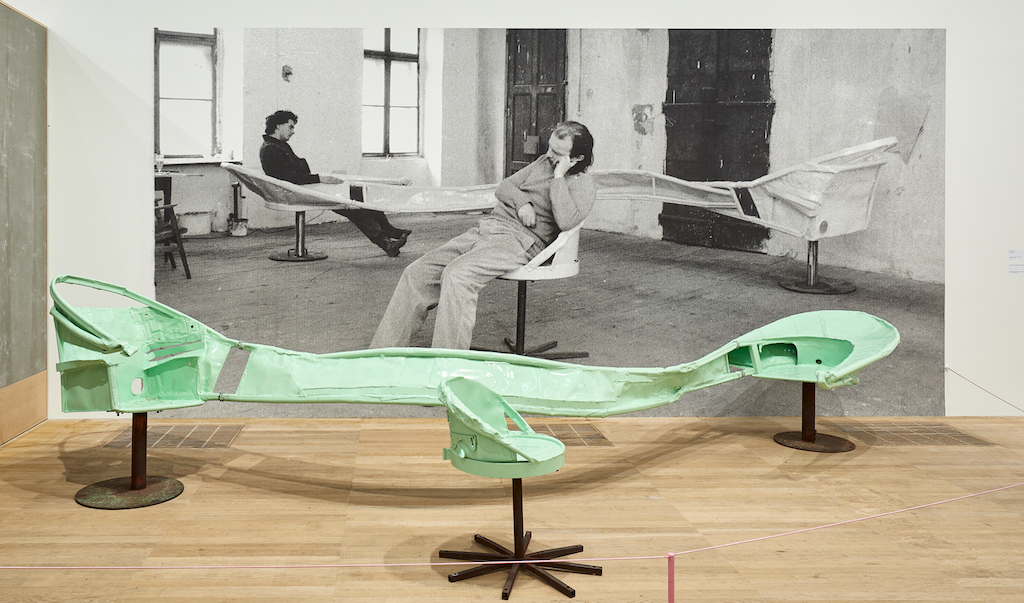

Soon the chairs were joined by sofas and love seats. Eo Ipso, 1987 (pictured below by Luke Walker) was made from his mother’s dismembered washing machine; its casing was stretched and twisted into an ungainly love seat and painted a vapid green. Made from reinforcing rods welded into an intricate web, Causeuse, 1990 resembles an instrument of torture rather than a piece of furniture. Tacked to the wall is a large slab of papier maché, roughly painted yellow ochre; the seat stands in front of it, as though it were worthy of prolonged contemplation. Its a joke, of course, but one that raises interesting questions about what art is for and how we appraise it. Two more chairs offer you the chance to meditate upon a huge pink sphere stuck with idiotic spikes that hangs above you like a child’s idea of a sputnik. The title Epiphanie an Stühlen, (Epiphany on a Chair) 2011 (pictured above left) ridicules the exaggerated claims often made for the transformative powers of art.

Soon the chairs were joined by sofas and love seats. Eo Ipso, 1987 (pictured below by Luke Walker) was made from his mother’s dismembered washing machine; its casing was stretched and twisted into an ungainly love seat and painted a vapid green. Made from reinforcing rods welded into an intricate web, Causeuse, 1990 resembles an instrument of torture rather than a piece of furniture. Tacked to the wall is a large slab of papier maché, roughly painted yellow ochre; the seat stands in front of it, as though it were worthy of prolonged contemplation. Its a joke, of course, but one that raises interesting questions about what art is for and how we appraise it. Two more chairs offer you the chance to meditate upon a huge pink sphere stuck with idiotic spikes that hangs above you like a child’s idea of a sputnik. The title Epiphanie an Stühlen, (Epiphany on a Chair) 2011 (pictured above left) ridicules the exaggerated claims often made for the transformative powers of art.

As his reputation grew, West began to apply his subversive humour to public sculptures. Using sheets of aluminium crudely welded to emphasise the seems or epoxy resin applied with oafish irregularity, he achieves a look of cack-handed amateurism. Painted in pastel colours inspired by kid’s pyjamas, several of them are livening up the dreary terrace behind the Blavatnik building with their wonky informality. My favourite is Untitled 2007, which like a melting ice cream, seems to be rapidly losing definition.

West may have played the fool, but he was desperate to be taken seriously. He devoured books on philosophy and sometimes used abstruse quotations as captions for the work. Based on a doodle, the pale blue curves of Schlieren, 2010 (main picture) were inspired by the Austrian born philosopher, Ludwig Wittgenstein who famously wrote: “Philosophers are often like little children, who first scribble random lines on a piece of paper with their pencils, and now ask an adult 'What is that?”

West’s work is like a endless investigation of the question “What is that… Is it art?” He died in 2012 and, in their eagerness to emphasise his significance, the Tate has tidied up and sanitised the work. Luckily, there’s a further selection at David Zwirner’s gallery where you can get close enough to see the guts and experience the restless energy and raw vitality of the artist’s approach.

West’s work is like a endless investigation of the question “What is that… Is it art?” He died in 2012 and, in their eagerness to emphasise his significance, the Tate has tidied up and sanitised the work. Luckily, there’s a further selection at David Zwirner’s gallery where you can get close enough to see the guts and experience the restless energy and raw vitality of the artist’s approach.

And there’s the added bonus of an extremely interesting show of paintings by West’s wife, Tamuna Sirbiladze whose sensual, looping forms explore the experience of the female body from the inside, as it were.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment