Paul Delvaux, the subject of a modest exhibition at the Blain Di Donna gallery in Mayfair, was JG Ballard’s favourite painter. The writer prized him for the creation of a complete world. Ballard found that world curious and inviting. He said he could spend hours gazing at the pictures wishing he could escape into their alternate reality. Ballard was made of sterner stuff than me. The places Delvaux paints seem quiet but harsh, not much happens but they feel menacing. They are sparsely populated and lonely. On the other hand, Ballard had a point about how compelling and intriguing he made his vision.

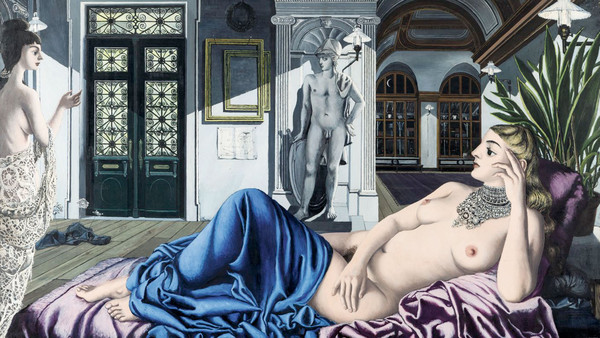

It is always either night or noon. The interiors are neo-classical apartments that belong to the European bourgeoisie from before the First World War, and they come with a full collection of Freudian indicators: locked doors, open windows, floors stripped down to the boards. The landscapes are either classical or barren and they have been emptied of all but a few people. The figures rarely interact with each other. No one speaks. The women always outnumber the men. They are thoughtful and distant, isolated but content and always utterly unapproachable. On the rare occasions they are clothed, it seems to be in the dress of the years before 1914: of Delvaux’s childhood.

While the work features a multitude of women, it is almost always only the same woman

If he had painted nothing else, Delvaux might have been thought of as a pupil of de Chirico and Magritte and consigned to the second rank of the Surrealist movement. But what makes Delvaux unforgettable are the women’s eyes. In the shape of perfect tears, they are exaggerated in size almost to the point of grotesqueness, the wide black pupils expanded to obliterate the iris and almost fill the cornea. These are the eyes of a seer or prophetess. They are always wide open, but never in alarm. They dominate the face but communicate zero emotion.

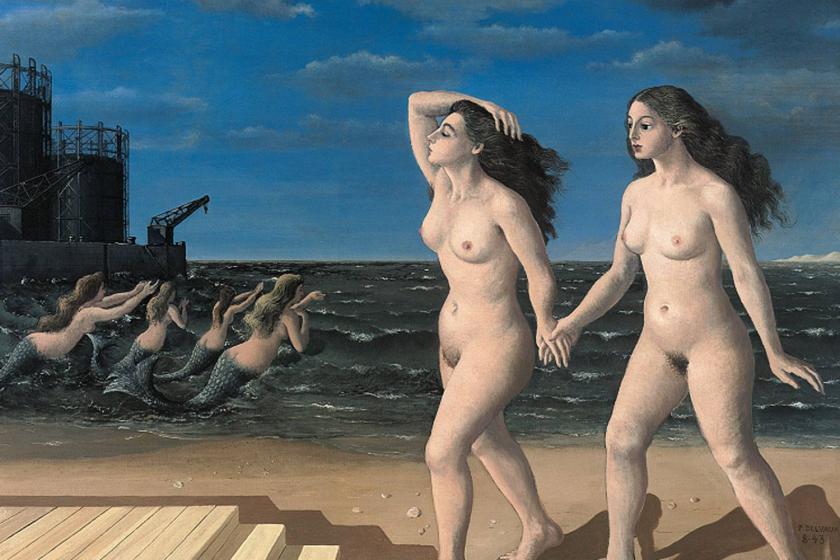

What do the women do? They lounge around more or less in the style of classical statuary. They gesture and pose, but it is difficult to establish what they are responding to. They cogitate, but never with a sense of heightened feelings. There is never any urgency. The Surrealists (though Delvaux did not refer to himself as such) always wanted to break through the rationalistic constraints of the prosaic, conscious world. When they did so, they ended up in another world that obeyed its own, mysterious logic (pictured below: L'Eloge de la Mélancolie, 1948).

Spend enough time painting naked, serene but unreachable women, and people will eventually wonder about your relationship with your mother. Sure enough, the catalogue essay tells us that he was “devoted” to his mother who was “sharply domineering and over-protective.” But there is no need to stress the amateur psychology too much, other than to say that while the work features a multitude of women, it is almost always only the same woman, repeated over and over with variations, but recognisably singular.

Spend enough time painting naked, serene but unreachable women, and people will eventually wonder about your relationship with your mother. Sure enough, the catalogue essay tells us that he was “devoted” to his mother who was “sharply domineering and over-protective.” But there is no need to stress the amateur psychology too much, other than to say that while the work features a multitude of women, it is almost always only the same woman, repeated over and over with variations, but recognisably singular.

By the time Delvaux got into his stride, the pioneering decades of Surrealism were over and the repertoire of symbols and signs was in place. Delvaux added nothing to them – except for those female eyes – and yet his work is instantly recognisable and entirely his own.

When he drifted away from his primary subject, the work becomes less sure. There are some paintings from the late Forties and early Fifties where the women have been replaced by skeletons (though he manages to convey the feeling that they are mostly female skeletons). There is heavy-handed religious imagery: skeletons in mourning, skeletons gathered round another skeleton lying on the ground. It’s the entombment of Christ imagined by Ray Harryhausen.

Delvaux shared the Surrealist fascination with popular culture. He loved the fantasies of Jules Verne. He was delighted by an exhibition of wax sculptures that displayed human, anatomical malformations. But he didn’t share their political obsessions. He was always an outsider from what could be termed the Surrealist establishment. This now seems like a wise move. It freed him to concentrate, with unusual dedication, on his sunny, antique landscapes or crepuscular townscapes, all containing their own small band of calm, hieratic and silent women.

This is an excellent small exhibition with many loans from private collections, which, presumably, will be difficult to see again any time soon.

Add comment